Posts Tagged ‘sita ram goel’

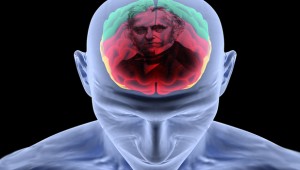

The ‘Hindoo’ Mind : Colonised by Macaulayism

‘ Macaulayism ‘ the term derives from Thomas Babington Macaulay, a member of the Governor General’s Council in the 1830s. Earlier, the British Government of India had completed a survey of the indigenous system of...

The Worlds Longest ‘Unknown’ War

That audacious armada of the religion of Hijaz – Whose insignia reached every corner of the world Which learnt no obstruction from any fear Which felt no hesitation in Persian Gulf or faltered in the Red Sea Which vali...

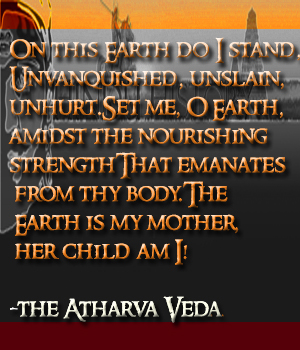

The Legacy of the Monotheism in Hindu India

The dialogue which Raja Ram Mohun Roy had started in the third decade of the nineteenth century stopped abruptly with the passing away of Mahatma Gandhi in January 1948. The Hindu leadership or what passed for it in post-indepe...

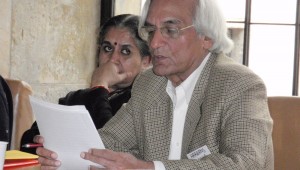

A Debate with an ‘Eminent’ Historian

Recently an e-mail exchange took place between my friend K. Venkat and the retired “eminent historian” Prof. Harbans Mukhia. Venkat himself gave a fitting reply to the august scholar’s opinions, which is circulating on th...