Hate mongers

Hate mongers often need concocted stories to buttress their political message. In India, these are most common in that peculiar Indian form of hatred: anti-Brahminism.

Hate mongers often need concocted stories to buttress their political message. In India, these are most common in that peculiar Indian form of hatred: anti-Brahminism.

As the local counterpart to what anti-Semitism has been in the West, it fantasizes about how Brahmins have only domination over us lesser mortals as their uppermost concern. Everything a Brahmin does, just has to be a wily stratagem to manipulate others.

With their greater book-orientedness and heavy over-representation in the writing professions, they control public discourse and make others look at the world through Brahminical glasses. No matter how you try to gain autonomy, they manage to outwit you, even to the point of taking control over progressive movements, even over anti-Brahminism.

Against such a formidable enemy, any means are justified. That may well be the reason why Abheek Barman chose to write the misleading opinion piece: “Why did PM Modi skip mentioning Savarkar at the Mathura rally?” (Economic Times, 27 May 2015). Alternatively, given the preponderance of borrowed, deformed and simply mistaken historical ideas in the anti-Brahmin movement, he may simply have been misinformed.

For starters, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar did not found “the ‘parivar’, that he started and which now holds the reins of power in New Delhi”.

For starters, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar did not found “the ‘parivar’, that he started and which now holds the reins of power in New Delhi”.

He was president of the rivalling Hindu Mahasabha in 1937-43, though not its founder: when it was created (1915 or 1922, depending on the definition), as also in 1925 when the RSS as backbone of the Parivar (family) was founded, he was in jail and barred from participating in politics.

He did, however, launch the concept Hindutva as a political category common to several Hindu Nationalist organizations, and indeed adopted as central to the RSS worldview.

Much is made also of Savarkar’s plea to the British for a lenient treatment, and his pledge of loyalty, after he had been confined to the Andaman Penal Colony.

Anti-Hindus let on their secret fear of Savarkar as a Hindu leader when they assert that he should have locked himself up in stern but sterile opposition, merely being heroic and dying – the very policy that the Rajputs pursued, ultimately to the detriment of the Hindu cause.

The truth is that Savarkar was too intelligent for that. He played his cards well and managed to actively serve the Hindu cause once again after his early release. It is this strategic acumen that Nehruvians like cannot forgive him for.

It must be admitted, though, that the anti-Hindu camp is very savvy in its use of arguments developed by anyone, as long as they are useful for the anti-Hindu cause. Seeing that Savarkar was being lionized by the Hindus, someone at the Communist fortnightly Frontline decided to belittle Savarkar as essentially a coward who had others do the killing that he planned, moreover a toady of the British.

I n reality, the British gave Savarkar two life sentences and many years of actual imprisonment for his proven anti-British opposition, much harsher than anything that the luxury inmates Gandhi and Nehru have had to endure, let alone the caviar Communists at Frontline.

n reality, the British gave Savarkar two life sentences and many years of actual imprisonment for his proven anti-British opposition, much harsher than anything that the luxury inmates Gandhi and Nehru have had to endure, let alone the caviar Communists at Frontline.

Their attempts to cut him to size only draw attention to the fact that they aren’t qualified to touch his feet. Yet, ill-conceived as this anti-Savarkar mudslinging was, it has been taken over by all anti-Hindu spokesmen and is now being used to maximum effect.

This contrasts with Hindutva behavior: when any new pro-Hindu argument is launched, the Hindu Nationalist movement will ignore it and fall back on the same worn-out outpourings of long-dead stalwarts like Guru Golwalkar, blind to the proven impotence of this outdated rhetoric.

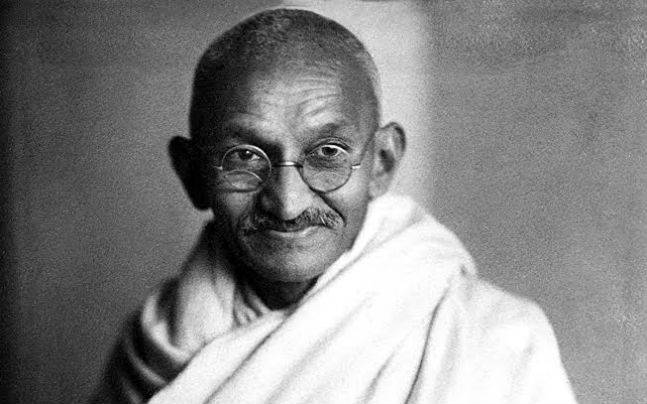

Gandhi

Then, we see Mahatma Gandhi for the umpteenth time called the “Father of the Nation”. Though quite vain (as when he condoned the crowd demanding that MA Jinnah address him as “Mahatma” rather than “Mister”), Gandhi himself would have rejected this epithet.

Then, we see Mahatma Gandhi for the umpteenth time called the “Father of the Nation”. Though quite vain (as when he condoned the crowd demanding that MA Jinnah address him as “Mahatma” rather than “Mister”), Gandhi himself would have rejected this epithet.

It stems from the new-fangled Nehruvian notion that India is a “nation in the making” conceived by the political unification under Queen Victoria, whereas Gandhi saw himself as a son of an age-old nation.

This falsehood is a cornerstone of the Nehruvian rhetoric, but then nobody in his right mind had considered falsity and Nehruism incompatible.

Gandhi is also termed an “implacable opponent of the British, who won independence for India”. Though admittedly very common worldwide, this myth crumbles when you investigate it properly.

His love of the British came out several times in successive wars when he organized military or humanitarian support for the British camp, or when he forced the apparent Congress candidate for the first Prime Ministership, Sardar Patel, to step down in favour of the anglicizer Jawaharlal Nehru.

The confused and contradictory course he charted, actually caused serious setbacks to the freedom movement. Ultimately it was Britain’s weakening in World War 2 and India’s heightened self-confidence through its wartime record that convinced the British to withdraw. As the decolonizing British PM Clement Attlee later confided, Gandhi’s role had been “minimal”.

Trinity

That Narendra Modi singled out Deendayal Upadhyaya, co-founder of the Jan Sangh, predecessor of the BJP, as “one of the three pillars of Indian politics”, together with Mahatma Gandhi and Ram Manohar Lohia, would be a fit topic for criticism, for it is indeed an ill-conceived choice.

That Narendra Modi singled out Deendayal Upadhyaya, co-founder of the Jan Sangh, predecessor of the BJP, as “one of the three pillars of Indian politics”, together with Mahatma Gandhi and Ram Manohar Lohia, would be a fit topic for criticism, for it is indeed an ill-conceived choice.

Lohia launched casteism in politics, a tendency here flatteringly referred to as opposition to “upper-caste domination over subalterns”. Gandhi’s policies of strict non-violence and economic primitivism, if followed, would have finished India long ago.

Upadhyaya had the merit of coining the phrase “Integral Humanism”, which in a nutshell says everything Dharmic politics should be. It would still be a good thing if the BJP today would highlight “Integral Humanism” as its real ideological commitment, instead of weasel terms like “Nationalism”. Call it “Dharma” for Indians and people with a vivid Indian connection, “Integral Humanism” for foreign consumption or in English-language media.

Unfortunately, in his elaboration of this bright idea, Upadhyaya proved too attached to the RSS fixation on a “national soul” (ultimately stemming from European Romantic thinker Johann Herder), which took up all the space in his booklet with the promising title. People who knew him confided to me that he was an all too ordinary man, which corresponds to the verifiable mediocrity of his ideas.

But for , these are trifles pertaining to the contents of his ideological work, unimportant next to the damning indictment that he was “a Brahmin” and “an early member of the RSS”. What much of ideology does consider, is sweeping and inaccurate (“hostile to the all ideas of individualism, capitalism, democracy and communism”), but we can put that down to the space constraints of a mere column.

Why not Savarkar?

Anyway, the crucial question for him is also crucial for us: “But why did Modi skip Savarkar, whose image in Parliament he paid homage to, soon after becoming PM?

Anyway, the crucial question for him is also crucial for us: “But why did Modi skip Savarkar, whose image in Parliament he paid homage to, soon after becoming PM?

The RSS celebrates him as ‘Veer’ or ‘valiant’. From the 1920s, he was the main ideologue of the RSS that came into being on Vijaya Dashami, 1925. Savarkar wrote its basic text, ‘Hindutva’ in 1923.”

Indeed, though Savarkar was formally not one of them, his Hindutva ideology was all-important to the RSS and its daughter organizations, including the present ruling party. Why did Modi not even mention him?

Has he been superseded by more recent Hindu ideologues, such as that other Jan Sangh president, Balraj Madhok, or by historian Sita Ram Goel, or by later converts to Hindu politics like Arun Shourie and Subramanian Swamy?

And it is not that Modi was shy about naming names. Mentioning Gandhi may have been in deference to the actual moral aura that the Mahatma still enjoys worldwide, and Upadhyaya may have been unavoidable for an RSS loyalist.

But he lionized Lohia of all people, the stalwart of the divisive casteist poison that has so long paralyzed Indian politics. He actually preferred the socialist caste-monger Lohia to Savarkar, as well to all other unnamed Hindu leaders and thinkers.

Could the reason be that Modi partakes of the intellectual culture of the RSS: borrowing from Nehruvian sources, playing by the rules laid down by the enemy? But such considerations are outside the Nehruvian worldview, which catalogues anything done by any Hindutva hate figure as wily, fanatic, part of a tough secret plan motivated by Hindu interests.

It just doesn’t occur to him that nominal Hindu Nationalists are really obedient playthings in his own side’s own hands. Not that they themselves fail to treat Hindus as enemies, but Hindus refuse to see this and treat them as their own standard, as their Guru. Even when securely in power, Hindu Nationalists still crawl before the secularist standard.

Savarkar’s sins

Anyway, Barman puts it down to a belated recognition of Savarkar’s own sins. The worst is of course that he was “a Chitpavan Brahmin”. At age 12 already, young Savarkar took a leadership role in a communal riot.

That he was an accomplice in the assassination of a British official should count as relatively good (if not the means, at least the purpose) for an avowed admirer of “implacable” opposition to the British.

Ah, but that admiration was only meant for Gandhi, the man responsible for many thousands of deaths during the Partition massacres, the man who let others do the killing (described as an act of cowardice in Savarkar’s case) all while keeping his own hands clean even to the point of becoming a by-word for non-violence.

Barman also claims that Savarkar “wrote of the ‘unity’ of all Hindus, but his writing had no place for Muslims, Sikhs or other communities”. It is only a dogma of the Nehruvians, including the separatist section among the Sikhs, that Sikhi is a separate religion.

From a scholarly viewpoint, of course Sikhs are Hindus: all Indian “unbelievers” were called just that by the Muslim invaders who introduced the very term “Hindu”.

And at least Barman should know that from a Hindutva viewpoint, Sikhs are Hindus just as Buddhists, Tribals and other Indian religionists are That precisely is what “the unity of all Hindus” means. Barman is a frog in the well who projects his own limited and ignorant Nehruvian worldview onto more mature views.

Then, Barman accuses Savarkar (and another Chitpavan Brahmin, prominent freedom fighter BG Tilak) of having espoused the Aryan Invasion Theory.

Then, Barman accuses Savarkar (and another Chitpavan Brahmin, prominent freedom fighter BG Tilak) of having espoused the Aryan Invasion Theory.

This is the cornerstone of British rule in India, of missionary propaganda and of the anti-Brahmin agitation among Tribals, Dalits, Dravidians; indeed, of Barman’s own anti-Brahminism.

And it is true that Savarkar was wrong in this regard, having been mesmerized by the then all-powerful belief that linguistics had somehow proven he Aryan invasion and thus overruled Hindu tradition, which knows of no Aryan invasion but only of several “Aryan” emigrations.

(But while Savarkar was wrong 90 years ago, under several constraints, the anti-Brahmin movement entertains the same mistake even today.) Contrary to Barman’s claims, it was not exported from India to Europe but had been invented in Europe ca. 1820, after several decades of assuming that the newly-discovered Indo-European language family had originated in India.

Let us face the fact here that Savarkar’s worldview was influenced by the then Zeitgeist (spirit of the times), which no longer obtains. Likewise, Mahatma Gandhi is badly outdated, as are Ram Manohar Lohia (though sinister disintegrationists including Barman try to keep his legacy alive) and Deendayal Upadhyaya. It was one of the worst traits of Hindu Nationalism that it refuses to grow and just keeps on hero-worshipping long-dead leaders without making their inspiration evolve with the times.

Savitri Devi

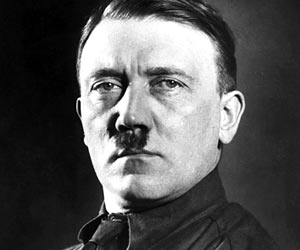

And then Barman gets really off track: “Savarkar’s story has a sinister follow up. By the late 1920s, a European woman called Miximiani Portas travelled to India, where faced with deportation, she married Asit Krishna Mukherji, then the only Indian supporter of Nazism and Japanese expansionism across Asia. (…) Inherently racist, but with a mystical awe of ancient Hindu and Egyptian civilisations, Savitri gobbled up Savarkar’s bizarre Aryan theories. (…) ideas of Aryan racial supremacy, and the inherent ‘sub-humanity’ of other people, travelled via Savitri Devi to Adolf Hitler.

And then Barman gets really off track: “Savarkar’s story has a sinister follow up. By the late 1920s, a European woman called Miximiani Portas travelled to India, where faced with deportation, she married Asit Krishna Mukherji, then the only Indian supporter of Nazism and Japanese expansionism across Asia. (…) Inherently racist, but with a mystical awe of ancient Hindu and Egyptian civilisations, Savitri gobbled up Savarkar’s bizarre Aryan theories. (…) ideas of Aryan racial supremacy, and the inherent ‘sub-humanity’ of other people, travelled via Savitri Devi to Adolf Hitler.

She believed that Hitler was the divine power that would deliver this world from the Kali Yuga. Savitri Devi – and Savarkar – helped Hitler form his bizarre racial theories.”

Having devoted a few hundred pages to the sad case of Savitri Devi (chapters in The Saffron Swastika, 2001, and in Return of the Swastika, 2007), I will not fill up this limited space with the many reasons why Barman’s version is worse than imaginary.

The reader merely has to consider the chronology to see that his story is impossible. Adolf Hitler wrote his Mein Kampf, full of “Aryan racial supremacy and the inherent ‘sub-humanity’ of other people” in 1923, when Maximiani Portas was a young student and Savarkar a prisoner.

The reader merely has to consider the chronology to see that his story is impossible. Adolf Hitler wrote his Mein Kampf, full of “Aryan racial supremacy and the inherent ‘sub-humanity’ of other people” in 1923, when Maximiani Portas was a young student and Savarkar a prisoner.

Until then, Savarkar had only written a few books about Indian history, which didn’t interest Hitler, and about the anti-colonial struggle, which Hitler strongly opposed.

So no, Savarkar did not influence Hitler and did not give him the very European idea of the Aryan race. (But at least, Mein Kampf and Savarkar’s Hindutva were written at the same time and both in captivity, a likeness about which astrologers and fantasy writers like Barman could certainly think up a good story.)

Maximiani Portas brought her Aryan theory with her into India, as she had learned it in Europe. She only took Indian ideas with her back to Europe when she could leave India at long last in 1945, too late for Hitler to learn anything from her. Incidentally, she had taken the name Savitri Devi shortly after settling in India, years before she married Mukherji.

It is but one of the many mistakes of detail accumulated in Barman’s brief column. She did have a peculiar veneration for Hitler as well as for Genghis Khan and for Pharaoh Akhenaten, the founder of monotheism and iconoclasm (a tradition that has particularly victimized Hinduism through Islam).

She prefigured the many Westerners who have travelled to India to brew their own combination of Hindu and Western ideas, and who often ended up getting sun-struck.

What Barman strategically omits, is that after the outbreak of World War 2, Savarkar immediately offered help in the anti-Nazi war effort and started recruiting for the British-Indian Army.

What Barman strategically omits, is that after the outbreak of World War 2, Savarkar immediately offered help in the anti-Nazi war effort and started recruiting for the British-Indian Army.

Indeed, Gandhi would deride him as a “recruiting officer”, forgetting how he himself as a British loyalist had recruited Indian volunteers for the British war effort in the Boer War, the Zulu War and World War 1.

Of course, in Barman’s game, it is “heads Hindus lose, tails anti-Hindus win”: if Savarkar had sided with the Axis against the British (as the secular Leftist Subhas Bose did), he would have been denounced as a proven Nazi, and now that he worked for the opposing camp, he is denounced as a British toady.

In reality, he had only India’s best interests at heart, which he thought were best served by enlisting in the British-Indian Army, just as Bose thought that enlisting in the Axis Armies was the best course to India’s independence. Barman with his puny divisive ideas would not understand, but Savarkar and Bose, for all their differences, were first of all patriots.

Conclusion

Whereas Nehruvians like to portray the RSS-BJP as a formidable enemy mercilessly pursuing the Hindu agenda, the fact is that most BJP stalwarts prefer to keep the Hindu agenda as far removed from their policies as possible. They serve their time in government and enjoy the perks of office, meanwhile hopefully cleaning up the economic mess that Congress has left behind, but never touching a serious Hindu concern with a barge-pole.

This even counts for the Prime Minister, whom Barman and his ilk have spent a dozen years demonizing as a Hindu fanatic.

The Hindutva once espoused by the Jan Sangh (1952-77) should be updated, the old formulas should be allowed to evolve, of course. But most BJP stalwarts are not interested in any evolution of their ideology, the only evolution they can conceive of is betrayal.

They have never developed an ideological backbone; instead, they have continuously borrowed conclusions from the Nehruvians and others who did their own thinking for non-Hindu purposes. They had the pick-pocket mentality of getting things on the cheap, of being mentally lazy and borrowing their ideas from elsewhere.

That is why both BJP Prime Ministers thus far, Atal Behari Vajpayee and now Modi, have professed their secularism. No, not age-old Hindu “secularism” (in the sense of religious pluralism) but the anti-Hindu ideology that is falsely called “secularism”. They essentially live up to the standards set by their enemies because their movement has never seriously developed a perspective of its own.

Also Read

Was Veer Savarkar a Nazi?

(2206)

We must discriminate between what we could call “absolute non-violence” and “relative non-violence.” Absolute non-violence means not even raising a hand even to defend oneself from unjust attack. Relative non-violence means only using violence to defend oneself and one’s community.

We must discriminate between what we could call “absolute non-violence” and “relative non-violence.” Absolute non-violence means not even raising a hand even to defend oneself from unjust attack. Relative non-violence means only using violence to defend oneself and one’s community.  Such dharmic warriors followed a long tradition including

Such dharmic warriors followed a long tradition including  To impose an artificial standard of non-violence on a society as a whole undermines the Kshatriya Dharma, or the political Dharma, and can damage the social order. It can undermine the will of a people to defend itself and weaken its sense of community identity. Those who have families and homes have a natural instinct to defend them when attacked. To tell such people that it is wrong for them to defend their loved ones is to make them feel guilty and confused.

To impose an artificial standard of non-violence on a society as a whole undermines the Kshatriya Dharma, or the political Dharma, and can damage the social order. It can undermine the will of a people to defend itself and weaken its sense of community identity. Those who have families and homes have a natural instinct to defend them when attacked. To tell such people that it is wrong for them to defend their loved ones is to make them feel guilty and confused. The great Swamis of India did not seek to undermine the Kshatriya Dharma. Adi Shankaracharya accepted the value of Kshatriya Dharma as he did a Vedic order for Hindu society. Let us also look at the example of the great Swami Vidyarananya of Sringeri (fourteenth century), an Advaitin (non-dualist) and a Mayavadin, who yet inspired two Hindu Kshatriyas who had become Muslims to reconvert to Hinduism and found the great Hindu kingdom of Vijayanagar to protect the Dharma. He did not ask for these Kshatriya rulers to follow absolute non‑violence.

The great Swamis of India did not seek to undermine the Kshatriya Dharma. Adi Shankaracharya accepted the value of Kshatriya Dharma as he did a Vedic order for Hindu society. Let us also look at the example of the great Swami Vidyarananya of Sringeri (fourteenth century), an Advaitin (non-dualist) and a Mayavadin, who yet inspired two Hindu Kshatriyas who had become Muslims to reconvert to Hinduism and found the great Hindu kingdom of Vijayanagar to protect the Dharma. He did not ask for these Kshatriya rulers to follow absolute non‑violence. To want to fight unrighteous people who are invading your country, or falsely ruling over your people, is the appropriate instinct of the Kshatriya, to deny which is to deny their vitality. Once the vitality of the Kshatriya – who represent the vital or energetic aspect of society – is weakened then the whole society can become devitalized. This dogmatic emphasis on non‑violence has set in motion a one‑sided teaching and a distortion that has weakened modern India.

To want to fight unrighteous people who are invading your country, or falsely ruling over your people, is the appropriate instinct of the Kshatriya, to deny which is to deny their vitality. Once the vitality of the Kshatriya – who represent the vital or energetic aspect of society – is weakened then the whole society can become devitalized. This dogmatic emphasis on non‑violence has set in motion a one‑sided teaching and a distortion that has weakened modern India. True Kshatriyas may come from any so-called caste today and are to be known by their character and their actions. Should there not be an adequate Kshatriya class in a country, all the other classes must take up a Kshatriya activity, even the Brahmins. In fact a true Brahmin must have learned the value of Kshatriya Dharma in order to be really able to go beyond it.

True Kshatriyas may come from any so-called caste today and are to be known by their character and their actions. Should there not be an adequate Kshatriya class in a country, all the other classes must take up a Kshatriya activity, even the Brahmins. In fact a true Brahmin must have learned the value of Kshatriya Dharma in order to be really able to go beyond it. Some fear that encouraging a Hindu Kshatriya would create a militant Hindu fundamentalism. They imagine paramilitary Hindu groups, Hindu terrorists, or Hindu Jihads, as is the situation in Islam today. However, Hinduism is a pluralistic religion quite unlike exclusive monotheistic religions that can easily create a fundamentalism of One God, One Savior and One Book. There is no history of Hindu Jihad, nor of any Hindu terrorist activity to conquer the world.

Some fear that encouraging a Hindu Kshatriya would create a militant Hindu fundamentalism. They imagine paramilitary Hindu groups, Hindu terrorists, or Hindu Jihads, as is the situation in Islam today. However, Hinduism is a pluralistic religion quite unlike exclusive monotheistic religions that can easily create a fundamentalism of One God, One Savior and One Book. There is no history of Hindu Jihad, nor of any Hindu terrorist activity to conquer the world. Should Hindus take a more active Kshatriya role, other political and social groups may raise the image of Mahatma Gandhi against them, though they themselves do not lead Gandhian lives. It is not service to the nation that motivates these people, or defense of the country, but their personal agendas and the politics of vote banks. No doubt the possibility of assertive Hinduism scares the leftists in India and they will try to discredit it with the image of Hindu militancy, if not fascism.

Should Hindus take a more active Kshatriya role, other political and social groups may raise the image of Mahatma Gandhi against them, though they themselves do not lead Gandhian lives. It is not service to the nation that motivates these people, or defense of the country, but their personal agendas and the politics of vote banks. No doubt the possibility of assertive Hinduism scares the leftists in India and they will try to discredit it with the image of Hindu militancy, if not fascism.

The common denominator in all these costly mistakes was a lack of realism.

The common denominator in all these costly mistakes was a lack of realism. During his prayer meeting on 1 May 1947, he prepared the Hindus and Sikhs for the anticipated massacres of their kind in the upcoming state of Pakistan with these words: “I would tell the Hindus to face death cheerfully if the Muslims are out to kill them. I would be a real sinner if after being stabbed I wished in my last moment that my son should seek revenge. I must die without rancour. (*) You may turn round and ask whether all Hindus and all Sikhs should die. Yes, I would say. Such martyrdom will not be in vain.” (Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, vol.LXXXVII, p.394-5) It is left unexplained what purpose would be served by this senseless and avoidable surrender to murder.

During his prayer meeting on 1 May 1947, he prepared the Hindus and Sikhs for the anticipated massacres of their kind in the upcoming state of Pakistan with these words: “I would tell the Hindus to face death cheerfully if the Muslims are out to kill them. I would be a real sinner if after being stabbed I wished in my last moment that my son should seek revenge. I must die without rancour. (*) You may turn round and ask whether all Hindus and all Sikhs should die. Yes, I would say. Such martyrdom will not be in vain.” (Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, vol.LXXXVII, p.394-5) It is left unexplained what purpose would be served by this senseless and avoidable surrender to murder. So, he was dismissing as cowards those who saved their lives fleeing the massacre by a vastly stronger enemy, viz. the Pakistani population and security forces. But is it cowardice to flee a no-win situation, so as to live and perhaps to fight another day? There can be a come-back from exile, not from death. Is it not better to continue life as a non-Lahorite than to cling to one’s location in Lahore even if it has to be as a corpse? Why should staying in a mere location be so superior to staying alive? To be sure, it would have been even better if Hindus could have continued to live with honour in Lahore, but Gandhi himself had refused to use his power in that cause, viz. averting Partition. He probably would have found that, like the butchered or fleeing Hindus, he was no match for the determination of the Muslim League, but at least he could have tried. In the advice he now gave, the whole idea of non-violent struggle got perverted.

So, he was dismissing as cowards those who saved their lives fleeing the massacre by a vastly stronger enemy, viz. the Pakistani population and security forces. But is it cowardice to flee a no-win situation, so as to live and perhaps to fight another day? There can be a come-back from exile, not from death. Is it not better to continue life as a non-Lahorite than to cling to one’s location in Lahore even if it has to be as a corpse? Why should staying in a mere location be so superior to staying alive? To be sure, it would have been even better if Hindus could have continued to live with honour in Lahore, but Gandhi himself had refused to use his power in that cause, viz. averting Partition. He probably would have found that, like the butchered or fleeing Hindus, he was no match for the determination of the Muslim League, but at least he could have tried. In the advice he now gave, the whole idea of non-violent struggle got perverted. t cannot be denied that Gandhian non-violence has a few successes to its credit. But these were achieved under particularly favourable circumstances: the stakes weren’t very high and the opponents weren’t too foreign to Gandhi’s ethical standards. In South Africa, he had to deal with liberal British authorities who weren’t affected too seriously in their power and authority by conceding Gandhi’s demands. Upgrading the status of the small Indian minority from equality with the Blacks to an in-between status approaching that of the Whites made no real difference to the ruling class, so Gandhi’s agitation was rewarded with some concessions. Even in India, the stakes were never really high. Gandhi’s Salt March made the British rescind the Salt Tax, a limited financial price to pay for restoring native acquiescence in British paramountcy, but he never made them concede Independence or even Home Rule with a non-violent agitation. The one time he had started such an agitation, viz. in 1930-31, he himself stopped it in exchange for a few small concessions.

t cannot be denied that Gandhian non-violence has a few successes to its credit. But these were achieved under particularly favourable circumstances: the stakes weren’t very high and the opponents weren’t too foreign to Gandhi’s ethical standards. In South Africa, he had to deal with liberal British authorities who weren’t affected too seriously in their power and authority by conceding Gandhi’s demands. Upgrading the status of the small Indian minority from equality with the Blacks to an in-between status approaching that of the Whites made no real difference to the ruling class, so Gandhi’s agitation was rewarded with some concessions. Even in India, the stakes were never really high. Gandhi’s Salt March made the British rescind the Salt Tax, a limited financial price to pay for restoring native acquiescence in British paramountcy, but he never made them concede Independence or even Home Rule with a non-violent agitation. The one time he had started such an agitation, viz. in 1930-31, he himself stopped it in exchange for a few small concessions. The ethical framework limiting the use of force to a minimum is known as “just war theory”, developed by European thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas and Hugo Grotius between the 13

The ethical framework limiting the use of force to a minimum is known as “just war theory”, developed by European thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas and Hugo Grotius between the 13