Posts Tagged ‘koenraad elst’

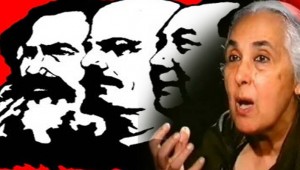

Romila Thapar mistakes Hindu impotent rage for a pro-Hindu power equation

According to retired history professor Romila Thapar, “academics must question more” (The Hindu, October 27, 2014). She was delivering the third Nikhil Chakravartty Memorial Lecture, eloquently titled: “To Question or not...

Romila Thapar’s Marxist Rant on ICHR nomination

Retired historian Romila Thapar has written an opinion piece (“History repeats itself”, 11 July 2014, India Today) giving the standard secular reaction to the appointment of equally retired historian Y. Sudershan Rao as cha...

A Debate with an ‘Eminent’ Historian

Recently an e-mail exchange took place between my friend K. Venkat and the retired “eminent historian” Prof. Harbans Mukhia. Venkat himself gave a fitting reply to the august scholar’s opinions, which is circulating on th...