According to retired history professor Romila Thapar, “academics must question more” (The Hindu, October 27, 2014). She was delivering the third Nikhil Chakravartty Memorial Lecture, eloquently titled: “To Question or not to Question: That is the Question”. The problem addressed by her was that “academics and experts shied away from questioning the powers of the day”. So, she “urge[d] intellectuals to resist assault on liberal thought”. In particular, she “asked a full house of Delhi’s intelligentsia on Sunday why changes in syllabi and objections to books were not being challenged”.

She was, hopefully, misinformed. (I shudder to think of the alternative explanation for this obvious untruth.) The recent changes in syllabi and objections to books by pro-Hindu activists, both phenomena being summed up in the single name of Dina Nath Batra, have met with plenty of vocal objections and petitions in protest, signed by leading scholars in India and abroad. I myself have signed two such petitions. At the European Indology conference in Zürich, July 2014, we were all given a petition to sign in support of Wendy Doniger’s book The Hindus: an Alternative History, which Batra’s judicial challenge had forced the publishers to withdraw. The general opinion among educated people, widely expressed, was to condemn all attempts at book-banning.

Selective indignation

To be sure, the intellectuals’ indignation was selective. There have indeed been cases where they have failed to come out in defence of besieged authors. No such storms of protest are raised when Muslims or Christians have books banned, or even when they assault the writers. Thus, several such assaults happened on the author and publisher of the Danish Mohammed cartoons, yet at its annual conference, the prestigious and agenda-setting American Academy of Religion hosted a panel where every single participant, including the speakers from the audience, supported the Muslim objections to the cartoons.

This trahison des clercs (“betrayal by the intellectuals”) is aptly explained by Thapar herself: “There are more academics in existence than ever before but most prefer not to confront authority even if it debars the path of free thinking. Is this because they wish to pursue knowledge undisturbed or because they are ready to discard knowledge, should authority require them to do so?”

The point is that the intellectual’s selective indignation shows very well where real authority lies. Threats of violence are, of course, highly respected. The day Hindus start assaulting writers they don’t like, you will see eminent historians like herself turning silent about Hindu censorship, or even taking up its defence — for that is what actually happens in the case of Islamic threats. Even more pervasive is the effect of threats to their careers. You will be in trouble if you utter any “Islamophobic” criticism of Islamic censorship, but you will earn praise if you challenge even proper judicial action against any anti-Hindu publications. This, then, safely predicts the differential behaviour of most intellectuals vis-à-vis free speech.

Box-type religions

A wholly different point is that she shows her partisan affiliation by adopting a secularized Christian framework when talking about Indian schools of thought. According to the newspaper report, “tracing the lineage of the modern public intellectual to Shramanic philosophers of ancient India, Prof. Thapar said the non-Brahminical thinkers of ancient India were branded as Nastikas or non-believers”.The division in Astika and Nastika already had different meanings at the time (not even exhausted by the two main ones: Vedic vs. non-Vedic, theistic vs. non-theistic), and did not coincide with the division in Brahmana vs. Shramana. Ancient Indian thought was never divided in box-type orthodoxies on the pattern of Christians vs. Muslims or Catholics vs. Protestants. It is only a Western projection, borrowed as somehow more prestigious by the Indian “secularists”, that imposes this categorization on the Indian landscape of ideas. Buddhist thinkers were never treated as dissenters, and even less so when Buddhism was politically in the ascendant.

She added an interesting image:

“I am reminded of the present day where if you don’t accept what Hindutva teaches, you’re all branded together as Marxists.”

The heavy-handed Marxist predominance in Indian academe is a historical fact of which she herself is a product as well as an icon, but now the notion is a bit dated. Today, many opportunists have shifted their loyalty to more fashionable new trends dictated by American universities, such as postmodernism, postcolonialism, multiculturalism, feminism and the more native contribution of subalternism. It is true that many Hindutva votaries are not up-to-date with the latest academic fashions, frozen as these outsiders are in old slogans. At any rate, the vibrant interaction of ancient India’s intellectual landscape, where free debate flourished, was nothing like the modern situation where her own school has locked out the Hindu voice and the latter has reactively demonized her.

Power equation

In her view, “public intellectuals, playing a discernible role, are needed for such explorations as also to articulate the traditions of rational thought in our intellectual heritage. This is currently being systematically eroded.” True, many intellectuals are not guided by what is true or “rational”, but only by what company they land up in if they get associated with a particular viewpoint. Numerous persons in academe and the media have loudly sung the anti-Hindu or “secular” tune when that was fashionable. Depending on how close their institutional position is to the new Narendra Modi government, you interestingly see many of them reposition themselves as somehow always having been pro-Hindu.

As she aptly said: “It is not that we are bereft of people who can think autonomously and ask relevant questions. But frequently where there should be voices, there is silence. Are we all being co-opted too easily by the comforts of conforming?”

But the power equation is such that the comforts of conforming still lead most to the anti-Hindu side. The opportunists changing sides are still a minority, the anti-Hindu discourse remains the dominant one. The best proof is that the ruling BJP, supposedly a Hindu party, is still acting out the worldview of the “secularists”. They are not actively challenging it or changing the intellectual power equation. It is perhaps fortunate for the Hindu side that the “secularists” have denounced it for so long as a Hindu party, for that is what makes the opportunists turn superficially pro-Hindu now.

So far, the ruling party is not repeating Murli Manohar Joshi’s attempt (ca. 2002) to rewrite the officially recommended history textbooks. That adventure ended in a demonstration of Hindu incompetence, a complete reversal once the “secularists” were back in power, and a strong reaffirmation of their intellectual predominance. Even though the BJP is back in power now, it still hesitates to challenge their conceptual framework.

Moral authority

According to the newspaper: “Prof. Thapar stressed that intellectuals were especially needed to speak out against the denial of civil rights and the events of genocide.” Yes, the genocide accompanying the birth of Pakistan and later of Bangladesh are two events that should not be forgotten, eventhough her own school has tried to whitewash, minimize or obscure them. The largest religious massacre of independent India’s history, that of the Sikhs by the Congress “secularists” in 1984, also comes in for closer scrutiny and for a demythologizing analysis about the true nature of Congress dynasticism.On a smaller scale, Hindus have also misbehaved, either out of smugness or out of desperation, and that too deserves study; except that it has already been made the object of publications so many times while the former subjects remain orphans.

The eminent historian is quoted as observing: “The combination of drawing upon wide professional respect, together with concern for society can sometimes establish the moral authority of a person and ensure public support.” Indeed, the impartisan nature of proper academic research would confer the moral authority to intervene, sparingly, in ongoing public debates. It is therefore a pity that so many scholars of her own school have squandered this moral authority by being so brazenly partisan.

No reaction?

Finally, she reiterated her main point, namely “the ease with which books are banned and pulped or demands made that they be burned and syllabi changed under religious and political pressure or the intervention of the state. Why do such actions provoke so little reaction from academics, professionals and others among us who are interested in the outcome of these actions? The obvious answer is the fear of the instigators — who are persons with the backing of political authority.”

Again, Prof. Thapar was misinformed. When Batra and other Hindus put publishers under pressure to withdraw Wendy Doniger’s book or AK Ramanujan’s Three Hundred Ramayanas, the publishers buckled under the fear of the Hindu public’s purchasing power. Apart from ideological factors, entrepreneurs also have to take into account the purely commercial aspect of a controversy. In this case, they took into account the only power that Hindus have: their numbers. But the Hindu instigators did not inspire “fear”, and definitely did not have “the backing of political authority”.

It is strange how fast people can forget. Modi has only very recently come to power. At the time of the Ramanujan and Doniger controversies, Congress was safely in power. If the publishers were in awe of any powers-that-be, it was of the Congress “secularists”.

More fundamentally, changes in government do not necessarily entail changes in the dominant intellectual framework. The accession to power (or rather, to office) of a nominally Hindu party does not mean that the ideological power equation has changed. In spite of the lip-service paid to Hindu self-respect by a few fashion-conscious opportunists, anti-Hindu “secularism” still rules the roost. Even now it furnishes the set of assumptions that most intellectuals, and even most ruling BJP politicians, go by.

(1502)

S.N. Balagangadhara, better known as Balu, is Professor of Comparative Culture Studies in Ghent University, Belgium. Balu is a Kannadiga Brahmin by birth, a former Marxist, and his discourse has a very in-your-face quality. In his latest book, Reconceptualizing India Studies (Oxford University Press 2012), the attentive reader will see a critique of the Indological establishment in the West and the political and cultural establishment in India. Like Rajiv Malhotra’s recent works, it questions their legitimacy. The reigning Indologists and India-watchers would do well to read it.

S.N. Balagangadhara, better known as Balu, is Professor of Comparative Culture Studies in Ghent University, Belgium. Balu is a Kannadiga Brahmin by birth, a former Marxist, and his discourse has a very in-your-face quality. In his latest book, Reconceptualizing India Studies (Oxford University Press 2012), the attentive reader will see a critique of the Indological establishment in the West and the political and cultural establishment in India. Like Rajiv Malhotra’s recent works, it questions their legitimacy. The reigning Indologists and India-watchers would do well to read it.

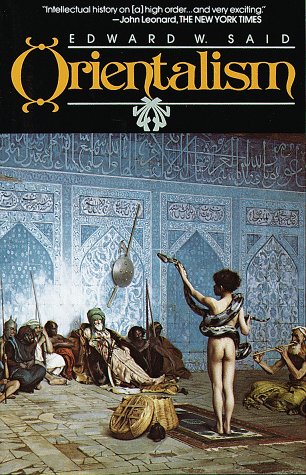

Look at the secularists, who for decades now have gone gaga over Said’s concept of Orientalism: “Orientalism is reproduced in the name of a critique of Orientalism. It is completely irrelevant whether one uses a Marx, a Weber or a Max Müller to do so. (…) the result is the same: uninteresting trivia, as far as the growth of human knowledge is concerned; but pernicious in its effect as far as Indian intellectuals are concerned.” (p.47) India has produced intellectual giants like (limiting ourselves to the 20th century:) R.C. Majumdar, P.V. Kane or A.K. Coomaraswamy, but the Indian secularists are intellectually very poor copies of their Western role models.

Look at the secularists, who for decades now have gone gaga over Said’s concept of Orientalism: “Orientalism is reproduced in the name of a critique of Orientalism. It is completely irrelevant whether one uses a Marx, a Weber or a Max Müller to do so. (…) the result is the same: uninteresting trivia, as far as the growth of human knowledge is concerned; but pernicious in its effect as far as Indian intellectuals are concerned.” (p.47) India has produced intellectual giants like (limiting ourselves to the 20th century:) R.C. Majumdar, P.V. Kane or A.K. Coomaraswamy, but the Indian secularists are intellectually very poor copies of their Western role models. Balu’s explanation of intercommunal relations in India and the state’s role therein is original and clear. In his opinion, the secular state is not there to curb religious violence, but is in fact the cause of this violence. He focuses on its position in the question of religious conversion, which is forbidden in some neighbouring countries and demanded to be forbidden by many Hindus (both Mahatma Gandhi and the Hindu nationalists). But it is upheld as a right by the Muslims and especially by the Christian missionaries — and by the “secular” state. The latter clearly takes a partisan stand in doing so; and it would also be partisan if it did the opposite. It is impossible to be impartisan.

Balu’s explanation of intercommunal relations in India and the state’s role therein is original and clear. In his opinion, the secular state is not there to curb religious violence, but is in fact the cause of this violence. He focuses on its position in the question of religious conversion, which is forbidden in some neighbouring countries and demanded to be forbidden by many Hindus (both Mahatma Gandhi and the Hindu nationalists). But it is upheld as a right by the Muslims and especially by the Christian missionaries — and by the “secular” state. The latter clearly takes a partisan stand in doing so; and it would also be partisan if it did the opposite. It is impossible to be impartisan. The whole “secular” discourse on “religion” and intercommunal relations is borrowed from Christianity. The basic framework to think about religion is informed by Western experiences and fails to see the radical difference between these and the native traditions: “the secular state assumes that the Semitic religions and the Hindu traditions are instances of the same kind” (p.203). In realities, Hindus and Parsis don’t missionize and refrain from basing their religions on a defining truth claim. By contrast, Christianity and Islam believe they offer the truth, and consequently want everyone to accept it.

The whole “secular” discourse on “religion” and intercommunal relations is borrowed from Christianity. The basic framework to think about religion is informed by Western experiences and fails to see the radical difference between these and the native traditions: “the secular state assumes that the Semitic religions and the Hindu traditions are instances of the same kind” (p.203). In realities, Hindus and Parsis don’t missionize and refrain from basing their religions on a defining truth claim. By contrast, Christianity and Islam believe they offer the truth, and consequently want everyone to accept it.