Early Life

Chandra Shekhar Azad was born on 23 July 1906 in Jujhautiya Brahmins family of Pandit Sitaram Tiwari and Jagrani Devi in the bhabara (of jhabua District)|madhy Pradesh. He spent his childhood in the village Bhabhra when his father was serving in the erstwhile estate of Alirajpur

He got the natural training of a hardy and rough life along with the Bhils who inhabited the wild region. From his Bhil friends, early in life, be learnt wrestling and swimming. He also became more skilled with the bow and arrow. He learnt to throw the Bhala or Javelin, to shoot straight, to ride and use the sword, in all of which he became proficient.

From his childhood, he remained a devotee of Hanuman throughout his life, and had a very strong Pehelwan(wrestler)-like body.

He was even called Bhimsen or Bhim Dada later. After the early education in Jhabua, he was sent to the Sanskrit Pathashala at Varanasi, where a near relative of the family, probably maternal uncle was then living. He returned home after a few months and he was admitted in the local school at Alirajpur. Again his father sent him to Benares for the boy exhibited a strange waywardness.

This time he remained there and studied properly. On the whole, he was an average student. Political Initiation From the very outset, he had a deep aversion for study which was of no real but to simply churn out quill drivers or babus for the use of the British Raj in India. His stay at Benares however had a salutary effect upon his life, for he came in contact with many young men and ideas.

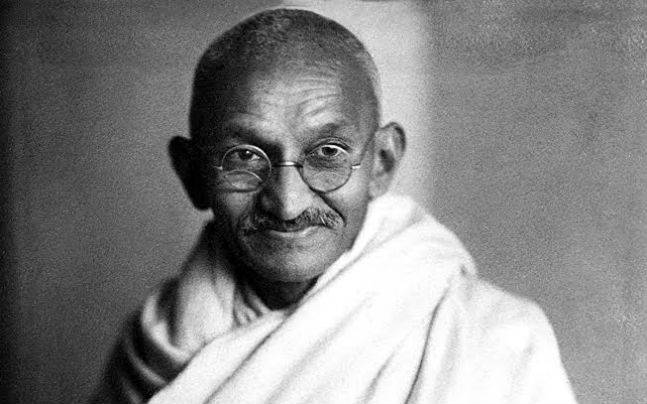

The atmosphere was such that he got the opportunity of studying many things, especially the unhappy events which were then happening in the country. Bit by bit, his mind was being drawn to the political situation of the country. Young Chandra Shekhar was fascinated by and drawn to the great national upsurge of the non-violent, non-cooperation movement of 1920-21 under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi.

The atmosphere was such that he got the opportunity of studying many things, especially the unhappy events which were then happening in the country. Bit by bit, his mind was being drawn to the political situation of the country. Young Chandra Shekhar was fascinated by and drawn to the great national upsurge of the non-violent, non-cooperation movement of 1920-21 under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi.

It is during this time, when the Jallianwala Baag massacre by British Army took place in Amritsar where hunderds (at least 2000) unarmed, peaceful and unwarned civilians were fired upon. This event had a profound effect on Indian national movement and inspired several young Indians, like Azad, into political movement for liberation. The young mind of Chandrashekhar was wax to receive and marble to retain.

From Chandrashekhar Tewari to Chandrashekhar ‘Azad’

To protest the massacre and demanding the liberation, various popular activities sprouted up throughout the country. While participating in one of these movements, Chandra Shekhar was arrested when he was just 16 years of age.

To protest the massacre and demanding the liberation, various popular activities sprouted up throughout the country. While participating in one of these movements, Chandra Shekhar was arrested when he was just 16 years of age.

He was brought to court. The Magistrate asked him, “What is your name? Where do you live? What is your father’s name?” His answers were going to become very famous. He gave his name as ‘Azad’, his father’s name as ‘Swatantra’ and his place of dwelling as ‘prison cell’. Astonished was the Magistrate at these straight and bold answers. Azad was sentenced to fifteen canes. He was beaten very severely. At every beat, his body turned blue and red and blood oozed out freely. Azad was highly honored by the citizens and profusely garlanded when he came out from jail. His photos appeared in the Press with streamlined captions. From here on, he would be known far and wide as ‘Azad’, forever.

After this incident, Shri Provesh, the chief organiser of the Revolutionary Party in India, sought him and persuaded him to join it. Azad proved to be a restless worker. He issued secretly and silently, many leaflets and bulletins to drive away the misconceptions entertained by the people of the country. He proved a master propagandist. In physical strength, none equaled him and he was called Bhim Dada. Other eminent members of the party working along with Azad were Shri Yogesh Chatterji, Shri Sachin Sanyal and Shri Rabindranath Kar. Men in the party learned all the arts of modern warfare. The main problem was finance. Finances! From where could the money be had? This was the major issue before the party. To ask openly was impossible and to obtain it secretly was a much more difficult task.

Kakori Case

The leaders of the party toured extensively in the land and collected a lot of money but it proved inadequate for the purposes of the contemplated actions. The leaders of the party sought the help of Azad. A secret commission was called and it decides in favour of dacoity of Government treasure. Verily it was a verdict and the men of the party started preparations for committing it somewhere. Result was the famous Kakori Case. Kakori is a railway station near Lucknow in Uttar Pradesh. The idea of the Kakori train robbery was conceived in the mind of Ram Prasad Bismil, while travelling by train from Shahjahanpur to Lucknow. At every station he noticed moneybags being taken into the guard�s van and being dropped into an iron safe. At Lucknow, he observed some loop holes in the special security arrangements. This was the beginning of the famous train dacoity at Kakori.

The leaders of the party toured extensively in the land and collected a lot of money but it proved inadequate for the purposes of the contemplated actions. The leaders of the party sought the help of Azad. A secret commission was called and it decides in favour of dacoity of Government treasure. Verily it was a verdict and the men of the party started preparations for committing it somewhere. Result was the famous Kakori Case. Kakori is a railway station near Lucknow in Uttar Pradesh. The idea of the Kakori train robbery was conceived in the mind of Ram Prasad Bismil, while travelling by train from Shahjahanpur to Lucknow. At every station he noticed moneybags being taken into the guard�s van and being dropped into an iron safe. At Lucknow, he observed some loop holes in the special security arrangements. This was the beginning of the famous train dacoity at Kakori.

As per the plan, on August 9, 1925 members successfully looted the No. 8 Down Train from Shahjahanpur to Lucknow by stopping it at a predetermined location and holding the British soldiers at gun point. Just 10 young men had done this difficult job because of their courage, discipline, above all, love for the country. They had written a memorable chapter in the history of India’s fight for freedom. These revolutionaries were Ramaprasad Bismil, Rajendra Lahiri, Thakur Roshan Singh, Sachindra Bakshi, Chadrasekhar Azad, Keshab Chakravarty, Banwari Lal, Mukundi Lal, Mammathnath Gupta and Ashfaqulla Khan.

After this event, the Government let loose a period of repression, search and arrests in the country. Many revolutionaries were arrested. After deliberations of 18 months, the court awarded punishments. Four of the members – Ramaprasad Bismil, Ashfaqulla Khan, Rajendra Lahiri and Roshan Singh were sentenced to death; the others were given life sentences. Sad was the outcome of this whole operation for it lost its best and powerful men in the scramble. However Azad remained at large, never to be captured by British, and to continue doing the revolutionary struggle. During the next phase of the struggle he menored a whole team of revolutionaries to shake the British Raj

After this event, the Government let loose a period of repression, search and arrests in the country. Many revolutionaries were arrested. After deliberations of 18 months, the court awarded punishments. Four of the members – Ramaprasad Bismil, Ashfaqulla Khan, Rajendra Lahiri and Roshan Singh were sentenced to death; the others were given life sentences. Sad was the outcome of this whole operation for it lost its best and powerful men in the scramble. However Azad remained at large, never to be captured by British, and to continue doing the revolutionary struggle. During the next phase of the struggle he menored a whole team of revolutionaries to shake the British Raj

Untired Revolutionary Organizer

Azad disguised as a Sadhu, came to Jhansi and from there via Khandwa came to Indore. For a few days he went to his birthplace Alirajpur but did not stay there for long. Again he came back to Indore and after staying there in disguise for sometime, he left Indore. For some time, he also remained hidden in a hanuman temple as a priest.

Taking a circuitous he traveled across the trackless jungle of the Vindhya valleys on foot. This was the hardest period in his life and he had to undergo many hardships. The sun scorched him by day and the cold chilled him by night.

Taking a circuitous he traveled across the trackless jungle of the Vindhya valleys on foot. This was the hardest period in his life and he had to undergo many hardships. The sun scorched him by day and the cold chilled him by night.

He was often at a loss to obtain food for himself.

He at last reached Kanpur where the headquarters of Hindustan Socialist Republican Army was set up, which Azad had to re-organize. This was the first task to fill the vacuum of leadership with capable youth.

At this time, he came in contact with the ablest and devoted men who wanted to overthrow the British Government by armed revolution. Incidentally, he met at Kanpur, Shri Bhagat Singh, Shri Rajguru and Shri Batukeshar Dutta.

The henchmen of the British Government were on the track of Azad. When a secret conference was being held between these men in a private lodging, the police all of a sudden rushed to the scene. A regular scuffle ensued and a party member named Shri Shukla met the assault single handed and was killed on the spot. Others, however, very skillfully managed to escape. Azad had in mind to teach a lesson to the intruders and on this particular occasion, he felt an overwhelming temptation to shoot but was held back.

The henchmen of the British Government were on the track of Azad. When a secret conference was being held between these men in a private lodging, the police all of a sudden rushed to the scene. A regular scuffle ensued and a party member named Shri Shukla met the assault single handed and was killed on the spot. Others, however, very skillfully managed to escape. Azad had in mind to teach a lesson to the intruders and on this particular occasion, he felt an overwhelming temptation to shoot but was held back.

Convocation of all the revolutionary leaders from different provinces of India was held in Delhi in September, 1928, near the old fort. Leaders from all over India took a serious review of the political situation in the country and decided on a course of action. Policy of “One for One” was decided in the terminology of the revolutionary organizations. Then, all of them departed to their respective provinces. It is rather difficult to know about the resolutions of meeting now.

Avenging the killing of Lala Lajpatrai

Hardly, had the leaders time to arrange their regional teams in order, than a serious situation arose in the country. Lala Lajpatrai, the ‘Lion of Punjab’ led a strong protest against the Simon commission in Lahore. The police with inhuman brutality charged the leaders with lathis.

Hardly, had the leaders time to arrange their regional teams in order, than a serious situation arose in the country. Lala Lajpatrai, the ‘Lion of Punjab’ led a strong protest against the Simon commission in Lahore. The police with inhuman brutality charged the leaders with lathis.

Lalaji was struck. It proved a deadly blow and later lies succumbed to his injuries. While dying he said, “The blows I got are but the death-knells of the British Empire in India”.

No sooner did Azad hear of this dastardly crime, then he turned black with rage. He rushed to Lahore and conferred there with his friends. Suitable action to avenge the insult was planned. It seemed to Azad that even his life would be too small a price to pay for the action. Selecting a few of his trusted followers, he explained to them the plan of his action and gave necessary instructions.

As previously arranged, this operation was directed by Chandrashekhar Azad, Rajguru, Bhagat Singh and Jaigopal. All these chiefs remained in hiding behind the Police Office in Lahore.

As previously arranged, this operation was directed by Chandrashekhar Azad, Rajguru, Bhagat Singh and Jaigopal. All these chiefs remained in hiding behind the Police Office in Lahore.

As soon as Scott and Saunders came out, a volley of bullets struck them. Saunders was killed and Scott saved himself. Thus, Lalaji’s death was avenged.

Martyrdom

Once again, Azad was never captured. Vigilant police of the British rule in India were on the look out for Azad. All attempts to catch him proved fruitless. There are numerous stories related to Azad�s hide and seek with British Raj during these days. He was an expert in using camouflage, which he used on various occasions. His stories of escaping the British police became the talk of common household. Police were bewildered and tired.

Once again, Azad was never captured. Vigilant police of the British rule in India were on the look out for Azad. All attempts to catch him proved fruitless. There are numerous stories related to Azad�s hide and seek with British Raj during these days. He was an expert in using camouflage, which he used on various occasions. His stories of escaping the British police became the talk of common household. Police were bewildered and tired.

At long last came the fateful day. On February 27, 1931 Azad was hiding in Alfred Park of Prayag, Allahabad in Utar Pradesh, waiting for a colleague for a secret meeting. Police had the clue and a successful net was drawn around the park.

There are some unconfirmed and somewhat controversial accounts of one of his comrades having been a traitor and police spy.

Anyways, police laid down a cordon with a troop of 80 sepoys to surround the Alfred Park and started fire. He only had a short range pistol with him and limited bullets. For quite sometime he held them at bay single-handedly with a small pistol and few cartridges.

Anyways, police laid down a cordon with a troop of 80 sepoys to surround the Alfred Park and started fire. He only had a short range pistol with him and limited bullets. For quite sometime he held them at bay single-handedly with a small pistol and few cartridges.

Fighting back bravely, he used the bullets to only target the british sepoys. In the end, Left with only one bullet, he fired it at his own temple and lived up to his resolve that he would never be arrested at the hands of British. He used to fondly recite a Hindi sher, probably his only poetic composition:

‘Dushman ki goliyon ka hum samna karenge,

Azad hee rahein hain, Azad hee rahenge’

“(Will face the enemies bullets’ Will remain free, Will Remain Free’)

( Chandra Shekhar Azad sacrifices his life from the movie Bhagat Singh)

(2255)

It is undeniable that Hindu Maha Sabha ideologue Savarkar spoke of reviving the “race spirit” of the Hindus. So did Golwalkar. Sri Aurobindo even used the term “Aryan race”, which to him meant exactly the same thing as “Hindu nation”,

It is undeniable that Hindu Maha Sabha ideologue Savarkar spoke of reviving the “race spirit” of the Hindus. So did Golwalkar. Sri Aurobindo even used the term “Aryan race”, which to him meant exactly the same thing as “Hindu nation”,  After 1945, the English language gradually lost the usage of the term “race” for the concept of “nation”; the Hindu nationalists followed suit. This was only natural: they had never cared for “race” in the biological sense so dear to the Nazis. The very concept of race, having been narrowed down to its biological meaning, has simply disappeared from their horizon. It is plainly untrue that Hindu ideologues at any time have shared Hitler’s racism.

After 1945, the English language gradually lost the usage of the term “race” for the concept of “nation”; the Hindu nationalists followed suit. This was only natural: they had never cared for “race” in the biological sense so dear to the Nazis. The very concept of race, having been narrowed down to its biological meaning, has simply disappeared from their horizon. It is plainly untrue that Hindu ideologues at any time have shared Hitler’s racism. Most secularists pretend not to know this unambiguous position of Savarkar’s (in many cases, they really don’t know, for Hindu-baiting is usually done without reference to primary sources). Likewise, Savarkar’s plea for caste intermarriage to promote the oneness of Hindu society is usually ignored in order to keep up the pretence that he was a reactionary on caste, an “upper-caste racist” (as Gyan Pandey puts it), and what not. There are no limits to secularist dishonesty, and so we are glad to find at least one voice in their crowd which does acknowledge these positions of Savarkar’s.

Most secularists pretend not to know this unambiguous position of Savarkar’s (in many cases, they really don’t know, for Hindu-baiting is usually done without reference to primary sources). Likewise, Savarkar’s plea for caste intermarriage to promote the oneness of Hindu society is usually ignored in order to keep up the pretence that he was a reactionary on caste, an “upper-caste racist” (as Gyan Pandey puts it), and what not. There are no limits to secularist dishonesty, and so we are glad to find at least one voice in their crowd which does acknowledge these positions of Savarkar’s. The first point rightly acknowledges that Savarkar, not being a historian, accepted the Aryan invasion theory promoted by prestigious seats of Western learning; and that he saw modern Hindus as a biological and cultural mixture of Aryan invaders and indigenous non-Aryans. He shared this view with Indian authors across the political spectrum, e.g. with Jawaharlal Nehru. Like Nehru, he saw no reason why people of diverse biological origins would be unable to form a united nation; the difference being that Nehru saw this unification as a project just started (“India, a nation in the making”), while Savarkar believed that this unification had come about in the distant past already.

The first point rightly acknowledges that Savarkar, not being a historian, accepted the Aryan invasion theory promoted by prestigious seats of Western learning; and that he saw modern Hindus as a biological and cultural mixture of Aryan invaders and indigenous non-Aryans. He shared this view with Indian authors across the political spectrum, e.g. with Jawaharlal Nehru. Like Nehru, he saw no reason why people of diverse biological origins would be unable to form a united nation; the difference being that Nehru saw this unification as a project just started (“India, a nation in the making”), while Savarkar believed that this unification had come about in the distant past already. Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke has written a book on the strange case of a French-Greek lady who converted to Hinduism and later went on to work for the neo-Nazi cause, Maximiani Portas a.k.a. Savitri Devi. The book is generally of high scholarly quality and full of interesting detail, but when it comes to Indian politics, the author is woefully misinformed by his less than impartisan sources.

Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke has written a book on the strange case of a French-Greek lady who converted to Hinduism and later went on to work for the neo-Nazi cause, Maximiani Portas a.k.a. Savitri Devi. The book is generally of high scholarly quality and full of interesting detail, but when it comes to Indian politics, the author is woefully misinformed by his less than impartisan sources. If one is inclined towards fascism, and one has the good fortune to live at the very moment of fascism’s apogee, it seems logical that one would seize the opportunity and join hands with fascism while the time is right. Conversely, if one has the opportunity to join hands with fascism but refrains from doing so, this is a strong indication that one is not that “fascist” after all. Many Hindu leaders and thinkers were sufficiently aware of the world situation in the second quarter of the twentieth century; what was their position vis-a-vis the Axis powers?

If one is inclined towards fascism, and one has the good fortune to live at the very moment of fascism’s apogee, it seems logical that one would seize the opportunity and join hands with fascism while the time is right. Conversely, if one has the opportunity to join hands with fascism but refrains from doing so, this is a strong indication that one is not that “fascist” after all. Many Hindu leaders and thinkers were sufficiently aware of the world situation in the second quarter of the twentieth century; what was their position vis-a-vis the Axis powers? And indeed, in the successful retreat from Dunkirk and in the British victories in North Africa and Iraq, Indian troops played a decisive role. It would earn the Hindus the gratitude of the British, or at least their respect. And if not that, it would instill the beginnings of fear in the minds of the British rulers: it would offer military training and experience to the Hindus, on a scale where the British could not hope to contain an eventual rebellion in the ranks. After the war, even without having to organize an army of their own, they would find themselves in a position where the British could not refuse them their independence.

And indeed, in the successful retreat from Dunkirk and in the British victories in North Africa and Iraq, Indian troops played a decisive role. It would earn the Hindus the gratitude of the British, or at least their respect. And if not that, it would instill the beginnings of fear in the minds of the British rulers: it would offer military training and experience to the Hindus, on a scale where the British could not hope to contain an eventual rebellion in the ranks. After the war, even without having to organize an army of their own, they would find themselves in a position where the British could not refuse them their independence. It is not unreasonable to suggest that Savarkar’s collaboration with the British against the Axis was opportunistic. He was not in favour of any foreign power, be it Britain, the US, the Soviet Union, Japan or Germany. He simply chose the course of action that seemed the most useful for the Hindu nation. But the point is: he could have opted for collaboration with the Axis, he could have calculated that a Hindu-Japanese combine would be unbeatable, he could even have given his ideological support to the Axis, but he did not. The foremost Hindutva ideologue, president of what was then the foremost political Hindu organization, supported the Allied war effort against the Axis.

It is not unreasonable to suggest that Savarkar’s collaboration with the British against the Axis was opportunistic. He was not in favour of any foreign power, be it Britain, the US, the Soviet Union, Japan or Germany. He simply chose the course of action that seemed the most useful for the Hindu nation. But the point is: he could have opted for collaboration with the Axis, he could have calculated that a Hindu-Japanese combine would be unbeatable, he could even have given his ideological support to the Axis, but he did not. The foremost Hindutva ideologue, president of what was then the foremost political Hindu organization, supported the Allied war effort against the Axis.  That HMS support to the anti-Nazi war effort was not merely tactical but to quite an extent also ideological, is shown by a series of statements by Nirmal Chandra Chatterjee, president of the Bengal Hindu Mahasabha and vice-president of the All-India Hindu Mahasabha. He declared in February 1941: “Our passionate adherence to democracy and freedom is based on the spiritual recognition of the Divinity of man. We are not only not communal but we are nationalists and democrats. The Anti-Fascist Front must extend from the English Channel to the Bay of Bengal.” (Hindu Politics, Calcutta 1945, p.13)

That HMS support to the anti-Nazi war effort was not merely tactical but to quite an extent also ideological, is shown by a series of statements by Nirmal Chandra Chatterjee, president of the Bengal Hindu Mahasabha and vice-president of the All-India Hindu Mahasabha. He declared in February 1941: “Our passionate adherence to democracy and freedom is based on the spiritual recognition of the Divinity of man. We are not only not communal but we are nationalists and democrats. The Anti-Fascist Front must extend from the English Channel to the Bay of Bengal.” (Hindu Politics, Calcutta 1945, p.13)  Yet, the British accused the Freedom Movement, including the HMS but also the Congress, of Nazi sympathies. Already in the 1930s, they had sometimes equated no less a person than Mahatma Gandhi with Hitler (a comparison which made Gandhian Congress activists feel proud). That was the only way they could hope to lessen the sympathy of the increasingly influential American public opinion for the Indian anti-colonial struggle.

Yet, the British accused the Freedom Movement, including the HMS but also the Congress, of Nazi sympathies. Already in the 1930s, they had sometimes equated no less a person than Mahatma Gandhi with Hitler (a comparison which made Gandhian Congress activists feel proud). That was the only way they could hope to lessen the sympathy of the increasingly influential American public opinion for the Indian anti-colonial struggle.