Posts Tagged ‘india’

Weapon Worship in India

There is an interesting cultural element of worshipping weapons in India. It is called Shastra Puja or Ayudha Puja, which literally means weapon worship. It takes place during an Indian religious annual festival in September. ...

Video : Acing Silambam in a Saree

Most urban, young women today see the saree as a dress for special occasions. Compared to modern attire, the saree is rather restricting and limits one’s movements. Not to mention how difficult it is to get a perfect drape if...

A brief talk on the history of Hampi by Sadhguru

During his travels, Sadhguru makes a stop in Hampi, the historic capitol of the Vijayanagar Empire. Surrounded by magnificent stones, cave carvings over 4000 years old, and exuding an aura of fascination, this city was once des...

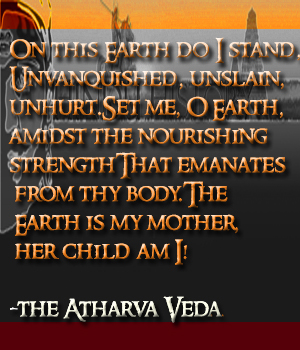

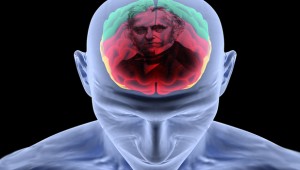

The ‘Hindoo’ Mind : Colonised by Macaulayism

‘ Macaulayism ‘ the term derives from Thomas Babington Macaulay, a member of the Governor General’s Council in the 1830s. Earlier, the British Government of India had completed a survey of the indigenous system of...

Reclaim civilisational self from shallow history texts

“Political considerations, ideological affiliations—especially of those who have always tried to establish an imported ideology—of well-resourced groups who have thrived in the Western academia by projecting India as a so...

Saraswati river sprouts to life after 4,000 years in Haryana

Haryana government’s efforts to trace the origin of the mythical Saraswati river bore fruit on Tuesday when water started gushing out from a pit, which was being dug under the lost river revival plan. As many as 80 people...

Chandra Shekhar Azad : The Immortal Revolutionary

Early Life Chandra Shekhar Azad was born on 23 July 1906 in Jujhautiya Brahmins family of Pandit Sitaram Tiwari and Jagrani Devi in the bhabara (of jhabua District)|madhy Pradesh. He spent his childhood in the village Bhabhra w...

The Forgotten Heroes: Hindu soldiers in the First World War

The narration of First World War is that war was predominantly European and was fought exclusively by Europeans. This is quite a long way departure from the truth. Today, while few would remember that Indian Corps won 13,000 me...

Sri Aurobindo : The Great Hindu Mystic and Visionary

“The will of a single hero can breathe courage into the hearts of a million cowards “ Sri Aurobindo was one of the greatest philosophers, revolutionary ,mystics and visionaries of modern history. He was a major leader in In...

The Legacy of the Monotheism in Hindu India

The dialogue which Raja Ram Mohun Roy had started in the third decade of the nineteenth century stopped abruptly with the passing away of Mahatma Gandhi in January 1948. The Hindu leadership or what passed for it in post-indepe...