Posts Tagged ‘hindus’

A brief talk on the history of Hampi by Sadhguru

During his travels, Sadhguru makes a stop in Hampi, the historic capitol of the Vijayanagar Empire. Surrounded by magnificent stones, cave carvings over 4000 years old, and exuding an aura of fascination, this city was once des...

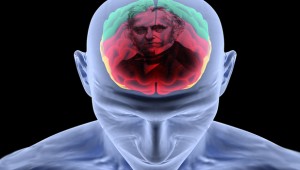

The ‘Hindoo’ Mind : Colonised by Macaulayism

‘ Macaulayism ‘ the term derives from Thomas Babington Macaulay, a member of the Governor General’s Council in the 1830s. Earlier, the British Government of India had completed a survey of the indigenous system of...

Did the British save Hindus ?

The idea, however, that the British have wrested the Empire from the Mohamadans is a mistake. The Mohamadans were beaten down — almost everywhere except in Bengal — before the British appeared upon the scene; Bengal they ...

Reclaim civilisational self from shallow history texts

“Political considerations, ideological affiliations—especially of those who have always tried to establish an imported ideology—of well-resourced groups who have thrived in the Western academia by projecting India as a so...

Jeremy Irons joins Dev Patel film The Man Who Knew Infinity

The British actor will star in the biopic of Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan, to be played by Dev Patel. Ramanujan conducted his mathematical research alone and without formal training, yet made extraordinary contribut...

Video : The Birth of Empire – The East India Company

Dan Snow travels through India in the footsteps of the company that revolutionised the British lifestyle and laid the foundations of today’s global trading systems. 400 years ago British merchants landed on the coast of I...

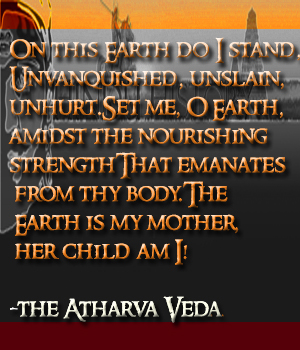

The Gita and the Freedom of India

The struggle against British colonialism marked a period when a huge number of Hindus became free from a very exploitative regime (and although the new regimes in India have eventually turned out just as worse as the British w...

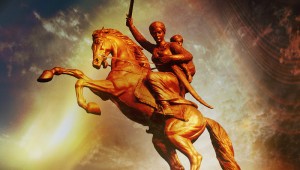

Lakshmi Bai : Warrior Queen of Jhansi

“We fight for independence. In the words of Lord Krishna, we will, if we are victorious, enjoy the fruits of victory; if defeated and killed on the field of battle, we shall surely earn eternal glory and salvation”-...

The Epic 27 Year War That Saved Hinduism

”Shivaji was the greatest Hindu king that India had produced within the last thousand years; one who was the very incarnation of lord Siva, about whom prophecies were given out long before he was born; and his advent was ...

A Pakistani in search of a homeland

In Eurasia Review on 25 December 2012, Khan A. Sufyan published a paper titled: “Pakistan: The True Heir Of Indus Valley Civilization – Analysis”. In it, he argues that Pakistan is not just the state for South-Asian Musli...

12