Posts Tagged ‘Featured’

This Is Spardha: Ancient Monastic Wrestling and the Rise of Indian MMA

When an Indian Kushti wrestler rolls in the earth, his hair and body become covered in the burnt-umber hue of soft clay. It’s said that he becomes “of one color.” This is meant literally of course — his black hair i...

Rajnath Singh says if Akbar is ‘great’, so is Rana Pratap

PRATAPGARH: In line with the Sangh Parivaar’s push for Hindu icons, Union home minister Rajnath Singh on Sunday asked historians to revisit history by giving Mewar ruler Maharana Pratap more credit. “I have no objec...

General Balbhadra Kunwar : The Hindu Lion of Nepal

While not much is known about the early life and exact year of birth, it is estimated that this brave Hindu warrior was born between 1775-90 in beautiful valley of Kathmandu home to the illustrious Pashupatinath temple. Balbhad...

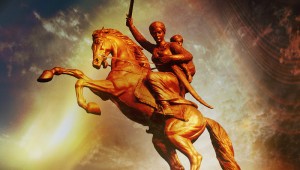

Lakshmi Bai : Warrior Queen of Jhansi

“We fight for independence. In the words of Lord Krishna, we will, if we are victorious, enjoy the fruits of victory; if defeated and killed on the field of battle, we shall surely earn eternal glory and salvation”-...

Rani Durgavati

Rani Durgavati was born on 5th October 1524 A.D. in the family of famous Chandel emperor Keerat Rai. She was born at the fort of Kalanjar (Banda, U.P.). Chandel Dynasty is famous in the Indian History for the valiant king Vidya...

The Epic 27 Year War That Saved Hinduism

”Shivaji was the greatest Hindu king that India had produced within the last thousand years; one who was the very incarnation of lord Siva, about whom prophecies were given out long before he was born; and his advent was ...

Learning from Mahatma Gandhi’s mistakes

Mahatma Gandhi is often praised as the man who defeated British imperialism with non-violent agitation. It is still a delicate and unfashionable thing to discuss his mistakes and failures, a criticism hitherto mostly confined t...

Origins of Anti-Brahminism

The true prophets of the anti-Brahmin message were no doubt the Christian missionaries. In the sixteenth century, Francis Xavier wrote that Hindus were under the spell of the Brahmanas, who were in league with evil spirits, and...

Was Veer Savarkar a Nazi?

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, commonly known as Swatantryaveer Savarkar was a courageous freedom fighter, social reformer, writer, dramatist, poet, historian, political leader and philosopher. Still widely unknown to the masses int...

Language Wars : Aryan vs Dravidian

Language Wars The chronological frame sketched is somewhat different from the dogma of the generation past. Then we were told that India was invaded around 1500 BC by Aryans from Central Asia or, perhaps, even South Europe. Thi...