Posts Tagged ‘east india company’

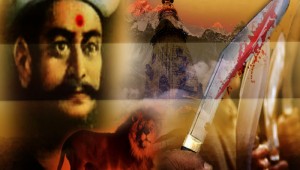

The Gurkha Khukri – A Saga of Snow, Steel, Blood and Sacrifice

While there are several legends about the origin of this blade called the Khukri, what is know is that origin of this blade lies in Nepal. Some say it was originated from a form of knife first used by the Mallas who came to pow...

Puli Thevar : The Ultimate Rebel Warrior

Long before Mangal Pandey who ignited the revolt of 1857, there was another Hindu , born in the land of the Raja Raja Cholan, who was the scourge of the enemies of Dharma. His name was Puli Thevar. The name Puli in Tamil means ...

General Balbhadra Kunwar : The Hindu Lion of Nepal

While not much is known about the early life and exact year of birth, it is estimated that this brave Hindu warrior was born between 1775-90 in beautiful valley of Kathmandu home to the illustrious Pashupatinath temple. Balbhad...

Swami Vivekananda’s Encounters with Christian Missionaries

Vivekananda not only carried the message of Hinduism to the USA and Europe during his two trips from 1893 to 1897 and from 1899 to 1900, he also turned the tide against Christianity in India so far as educated, upper class Hind...

Rani Chennamma

Rani Chennamma (October 23, 1778 – February 21, 1829) was the Queen of Kittur in Karnataka, southern India. In her youth she received training in horse riding, sword fighting and archery. She became queen of her native king...