”Shivaji was the greatest Hindu king that India had produced within the last thousand years; one who was the very incarnation of lord Siva, about whom prophecies were given out long before he was born; and his advent was eagerly expected by all the great souls and saints of Maharashtra as the deliverer of the Hindus from the hands of the Mlecchas, and as one who succeeded in the reestablishment of Dharma which had been trampled underfoot by the depredations of the devastating hordes of the Moghals” – Swami Vivekananda

Schoolchildren in India learn a very specific blend of Indian history. This school version of history is stripped of all the vigor and pride. The story of Indian civilization spans thousands of years. However for the most part the schoolbook version dwells on the freedom struggle against British and important role played in there by the Indian National Congress. We learn each and every movement of Gandhi and Nehru, but not even a passing reference is made to hundreds of other important people and events.

My objection is not to the persons Gandhi or Nehru. They were great men. However the attention they get and the exposure their political views and ideology gets is rather disproportionate.

And thus it comes no surprise to me that rarely we talk about an epic war that significantly altered the face of Indian subcontinent. The war that can be described the mother of all wars in India. Considering the average life expectancy that time was around 30 years, this war of 27 years lasted almost the lifespan of an entire generation. The total number of battles fought was in hundreds. It occurred over vast geographical expanse spanning four biggest states of modern India- Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka. For time, expanse and human and material cost, this war has no match in Indian history.

Intro

It started in 1681 with the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb’s invasion of Maratha empire. It ended in 1707 with Aurangzeb’s death. Aurangzeb threw everything he had in this war. He lost it all.

It started in 1681 with the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb’s invasion of Maratha empire. It ended in 1707 with Aurangzeb’s death. Aurangzeb threw everything he had in this war. He lost it all.

It’s tempting to jump into the stories of heroics, but what makes the study of war more interesting is the understanding of politics behind it. Every war is driven by politics. Rather war is just one of the means to do politics. This war was not an exception.

Shivaji’s tireless work for most of his life had shown fruits by the last quarter of seventeenth century. He had firmly established Marathas as power in Deccan. He built hundreds of forts in Konkan and Sahyadris and thus created a defense backbone. He also established strong naval presence and controlled most of the Western ports barring few on end of Indian peninsula. Thus tightening the grip on trade routes of Deccan sultanates, he strangled their weapons import from Europe and horses import from Arabian traders. These Sultanates launched several campaigns against Shivaji, but failed to stop him.

On the Northern front, several Rajput kings had accepted to be the vassals of Mughals. Aurangzeb had succeeded to the throne after brutal killing of his brothers and imprisonment of his father. With Rajput resistance mostly subsided and the southern sultanates weakened, it was only matter of time before Marathas were in his cross-hair.

[quote]‘The death of Shivaji was the mere beginning of Maratha history. He founded a Hindu principality-it had yet to grow into a Hindu Empire. This was all done after the death of Shivaji. The real epic opens as soon as Shivaji, after calling into being the great forces that had to act it up, disappears from the scene. ‘ ...Vināyak Dāmodar Sāvarkar[/quote]

Shivaji’s death

At the time of Shivaji’s death in 1680, Maratha empire spanned an area far more than the current state of Maharashtra and had taken firm roots. But it was surrounded by enemies from all sides. Portuguese on northern Coast and Goa, British in Mumbai, Siddies in Konkan and remaining Deccan sultanates in Karnataka posed limited challenge each, but none of them was capable of taking down the Marathas alone. Mughal empire with Aurangzeb at its helm was the most formidable foe.

At the time of Shivaji’s death in 1680, Maratha empire spanned an area far more than the current state of Maharashtra and had taken firm roots. But it was surrounded by enemies from all sides. Portuguese on northern Coast and Goa, British in Mumbai, Siddies in Konkan and remaining Deccan sultanates in Karnataka posed limited challenge each, but none of them was capable of taking down the Marathas alone. Mughal empire with Aurangzeb at its helm was the most formidable foe.

For the most part, Aurangzeb was a religious fanatic. He had distanced Sikhs and Rajputs because of his intolerant policies against Hindus. After his succession to the throne, he had made life living hell for Hindus in his kingdom. Taxes like Jizya tax were imposed on Hindus. No Hindu could ride in Palanquin. Hindu temples were destroyed and abundant forcible conversions took place. Aurangzeb unsuccessfully tried to impose Sharia, the Islamic law. This disillusioned Rajputs and Sikhs resulting in their giving cold shoulder to Aurangzeb in his Deccan campaign.

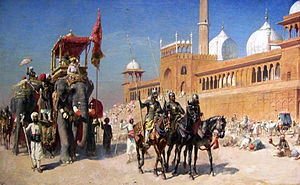

Thus in September of 1681, after settling his dispute with the royal house of Mewar, Aurangzeb began his journey to Deccan to kill the Maratha confederacy that was not even 50 years old. On his side, the Mughal king had enormous army numbering half a million soldiers, a number more than three times that of the Maratha army. He had plentiful support of artillery, horses, elephants. He also brought huge wealth in royal treasuries. Teaming up with Portuguese, British ,Siddis, Golkonda and Bijapur Sultanates he planned to encapsulate Marathas from all sides and to form a deadly death trap. To an outsider, it would seem no-brainer to predict the outcome of such vastly one sided war. It seemed like the perfect storm headed towards Maratha confederacy.

Enormous death and destruction followed in Deccan for what seemed like eternity. But what happened at the end would defy all imaginations and prove every logic wrong. Despite lagging in resources on all fronts, it would be the Marathas who triumphed. And at the expense of all his treasure, army, power and life, it would be the invading emperor who learned a very costly lesson, that the will of people to fight for their freedom should never be underestimated.

Timeline – Marathas under King Sambhaji (1680 to 1689):

After the death of Shivaji in 1680, a brief power struggle ensued in the royal family. Finally Sambhaji became the king. By this time Aurangzeb had finished his North missions and was pondering a final push in Deccan to conquer all of the India.

After the death of Shivaji in 1680, a brief power struggle ensued in the royal family. Finally Sambhaji became the king. By this time Aurangzeb had finished his North missions and was pondering a final push in Deccan to conquer all of the India.

In 1681 sambhaji attacked Janjira, but his first attempt failed. In the same time one of the Aurangzeb’s generals, Hussein Ali Khan , attacked Northern Konkan. Sambhaji left janjira and attacked Hussein Ali Khan and pushed him back to Ahmednagar. By this time monsoon of 1682 had started. Both sides halted their major military operations. But Aurangzeb was not sitting idle. He tried to sign a deal with Portuguese to allow mughal ships to harbor in Goa. This would have allowed him to open another supply route to Deccan via sea. The news reached sambhaji. He attacked Portuguese territories and pushed deep inside Goa. But Voiceroy Alvor was able to defend Portuguese headquarters.

By this time massive Mughal army had started gathering on the borders of Deccan. It was clear that southern India was headed for one big conflict.Sambhaji had to leave Portuguese expedition and turn around. In late 1683, Aurangzeb moved to Ahmednagar. He divided his forces in two and put his two princes, Shah Alam and Azam Shah, in charge of each division. Shah alam was to attack South Konkan via Karnataka border while Azam Shah would attack Khandesh and northern Maratha territory. Using pincer strategy, these two divisions planned to circle Marathas from South and North and isolate them.

The beginning went quite well. Shah Alam crossed Krishna river and entered Belgaum. From there he entered Goa and started marching north via Konkan. As he pushed further,he was continuously harassed by Marathas. They ransacked his supply chains and reduced his forces to starvation. Finally Aurangzeb sent Ruhulla Khan for his rescue and brought him back to Ahmednagar. The first pincer attempt failed.

The beginning went quite well. Shah Alam crossed Krishna river and entered Belgaum. From there he entered Goa and started marching north via Konkan. As he pushed further,he was continuously harassed by Marathas. They ransacked his supply chains and reduced his forces to starvation. Finally Aurangzeb sent Ruhulla Khan for his rescue and brought him back to Ahmednagar. The first pincer attempt failed.

After 1684 monsoon, Aurangzeb’s another general Sahabuddin Khan directly attacked the Maratha capital, fort Raygad. Maratha commanders successfully defended Raygad. Aurangzeb sent Khan Jehan for help, but Hambeerrao Mohite, Commander-in-Chief of Maratha army, defeated him in a fierce battle at Patadi. Second division of Maratha army attacked Sahabuddin Khan at Pachad, inflicting heavy losses on Mughal army.

In early 1685, Shah Alam attacked South again via Gokak- Dharwar route. But Sambhaji’s forces harassed him continuously on the way and finally he had to give up and thus failed to close the loop second time.

In april 1685 Aurangzeb rehashed his strategy. He planned to consolidate his power in the South by taking expeditions to Goalkonda and Bijapur. Both were Shia muslim rulers and Aurangzeb was no fond of them. He broke his treaties with both empires and attacked them. Taking this opportunity Marathas launched offensive on North coast and attacked Bharuch. They were able to evade the mughal army sent their way and came back with minimum damage.

On Aurangzeb’s new Southern front, things were proceeding rather smoothly. Bijapur fell in September 1686. King Sikandar Shah was captured and imprisoned. Goalkonda agreed to pay huge ransom. But after receiving the money, Aurangzeb attacked them in blatant treachery. Soon Goalkonda fell as well. King Abu Hussein of Goalkonda was captured and met the same fate as Sikandar Shah.

Marathas had tried to win mysore through diplomacy. Kesopant Pingle, (Moropant Pingle’s brother) was running negotiations, but the fall of Bijapur to mughals turned the tides and Mysore was reluctant to join Marathas. Still Sambhaji successfully courted several Bijapur sardars to join Maratha army.

Marathas had tried to win mysore through diplomacy. Kesopant Pingle, (Moropant Pingle’s brother) was running negotiations, but the fall of Bijapur to mughals turned the tides and Mysore was reluctant to join Marathas. Still Sambhaji successfully courted several Bijapur sardars to join Maratha army.

After fall of Bijapur and Goalkonda, Aurangzeb turned his attention again to his main target – Marathas. First few attempts proved unsuccessful to make a major dent. But in Dec 1688 he had his biggest jackpot. Sambhaji was captured due to treachery at Sangmeshwar. Aurangzeb gave him option of converting to Islam, which he refused. Upon refusal, Aurangzeb, blinded by his victories, gave Sambhaji the worst treatment he could ever give to anyone.Sambhaji was paraded on donkey. His tongue was cut, eyes were gorged out. His body was cut into pieces and fed to dogs.

There were many people who did not like Sambhaji and thus were sympathetic to Mughals. But this barbaric treatment made everyone angry. Maratha generals gathered on Raygad. The decision was unanimous. All peace offers were to be withdrawn. Mughals would be repelled at all costs. Rajaram succeeded as the next king. He began his reign by a valiant speech on Raygad. All Maratha generals and councilmen united under the flag of new king, and thus began the second phase of the epic war.

“Whenever Mughal horses used to refuse to go to the water to drink water, it was feared they had seen Santaji and Dhanaji” – Kafi Khan Mughal court historian

27 Years War TimeLine – Marathas under King Rajaram (1689 to 1700)

To Aurangzeb, the Marathas seemed all but dead by end of 1689. But this would prove to be almost a fatal blunder. In March 1690, the Maratha commanders, under the leadership of Santaji Ghorpade launched the single most daring attack on mughal army. They not only attacked the army, but sacked the tent where the Aurangzeb himself slept. Luckily Aurangzeb was elsewhere but his private force and many of his bodyguards were killed.

This positive development was followed by a negative one for Marathas. Raigad fell to treachery of Suryaji Pisal. Sambhaji’s queen, Yesubai and their son, Shahu, were captured.

Mughal forces, led by Zulfikar Khan, continued this offensive further South. They attacked fort Panhala. The Maratha killedar of Panhala gallantly defended the fort and inflicted heavy losses on Mughal army. Finally Aurangzeb himself had to come. Panhala surrendered.

Maratha ministers had foreseen the next Mughal move on Vishalgad. They made Rajaram leave Vishalgad for Jinji, which would be his home for next seven years. Rajaram travelled South under escort of Khando Ballal and his men. The queen of Bidnur, gave them supplies and free passage. Harji Mahadik’s division met them near Jinji and guarded them to the fort. Rajaram’s queen was escorted out of Maharashtra by Tungare brothers. She was taken to Jinji by different route. Ballal and Mahadik tirelessly worked to gather the scattered diplomats and soldiers. Jinji became new capital of Marathas. This breathed new life in Maratha army.

Aurangzeb was frustrated with Rajaram’s successful escape. His next move was to keep most of his force in Maharashtra and dispatch a small force to keep Rajaram in check. But the two Maratha generals, Santaji ghorpade and Dhanaji Jadhav would prove more than match to him.

They first attacked and destroyed the force sent by Aurangzeb to keep check on Rajaram, thus relieving the immediate danger. Then they joined Ramchandra Bavadekar in Deccan. Bavdekar, Vithoji Bhosale and Raghuji Chavan had reorganized most of the Maratha army after defeats at Panhala and Vishalgad.

In late 1691, Bavdekar, Pralhad Niraji , Santaji ,Dhanaji and several Maratha sardars met in Maval region and reformed the strategy. Aurangzeb had taken four major forts in Sahyadrais and was sending Zulfikar khan to subdue the fort Jinji. So according to new Maratha plan, Santaji and Dhanaji would launch offensives in the East to keep rest of the Mughal forces scattered. Others would focus in Maharashtra and would attack a series of forts around Southern Maharashtra and Northern Karnataka to divide Mughal won territories in two, thereby posing significant challenge to enemy supply chains. Thanks to Shivaji’s vision of building a navy, Marathas could now extend this divide into the sea, checking any supply routes from Surat to South.

The execution began. In early 1692 Shankar Narayan and Parshuram Trimbak recaptured Rajgad and Panhala. In early 1693 Shankar Narayan and Bhosale captured Rohida. Sidhoji Gujar took Vijaydurg. Soon Parshuram Trimbak took Vishalgad. Kanhoji Angre, a young Maratha Naval officer that time, took fort Kolaba.

While this was in work, Santaji and Dhanaji were launching swift raids on Mughal armies on East front. This came as a bit of surprise to Aurangzeb. In spite of losing one King and having second king driven away, Marathas were undaunted and actually were on offensive. From Khandesh, Ahmednagar to Bijapur to Konkan and Southern Karnataka, Santaji and Dhanaji wrecked havoc. Encouraged by the success, Santaji and Dhanaji hatched new action plan to attack Mughal forces near Jinji. Dhanaji Jadhav attacked Ismail Khan and defeated him near Kokar. Santaji Ghorpade attacked Ali Mardan Khan at the base of Jinji and captured him. With flanks cleared, both joined hands and laid a second siege around the Mughal siege at Jinji.

Julfikar khan, who was orchestrating Jinji siege, left the siege on Aurangzeb’s orders and marched back. Santaji followed him to North, but was defeated by Julfikar Khan. Santaji then diverted his forces to Bijapur. Aurangzeb sent another general Kasim Khan to tackle Santaji. But Santaji attacked him with a brilliant military maneuver near Chitaldurg and forced him take refuge in Dunderi fort. The fort was quickly sieged by Santaji and the siege only ended when most of the Mughal soldiers starved and Kasim Khan committed suicide. Aurangzeb sent Himmat Khan to reinforce Kasim Khan. Himmat khan carried heavy artillery. So Santaji lured him in a trap in the forest near Dunderi. A sudden, ambush style attack on Mughals was followed by a fierce battle. The battle ended when when Himmat Khan was shot in head and died. All his forces routed and Santaji confiscated a big cache of weapons and ammunition.

Julfikar khan, who was orchestrating Jinji siege, left the siege on Aurangzeb’s orders and marched back. Santaji followed him to North, but was defeated by Julfikar Khan. Santaji then diverted his forces to Bijapur. Aurangzeb sent another general Kasim Khan to tackle Santaji. But Santaji attacked him with a brilliant military maneuver near Chitaldurg and forced him take refuge in Dunderi fort. The fort was quickly sieged by Santaji and the siege only ended when most of the Mughal soldiers starved and Kasim Khan committed suicide. Aurangzeb sent Himmat Khan to reinforce Kasim Khan. Himmat khan carried heavy artillery. So Santaji lured him in a trap in the forest near Dunderi. A sudden, ambush style attack on Mughals was followed by a fierce battle. The battle ended when when Himmat Khan was shot in head and died. All his forces routed and Santaji confiscated a big cache of weapons and ammunition.

By now, Aurangzeb had the grim realization that the war he began was much more serious than he thought. He consolidated his forces and rethought his strategy. He sent an ultimatum to Zulfikar khan to finish Jinji business or be stripped of the titles. Julfikar khan tightened the Siege. But Rajaram fled and was safely escorted to Deccan by Dhanaji Jadhav and Shirke brothers. Haraji Mahadik’s son took the charge of Jinji and bravely defended Jinji against Julfikar khan and Daud khan till January of 1698. This gave Rajaram ample of time to reach Vishalgad.

Jinji fell, but it did a big damage to the Mughal empire. The losses incurred in taking Jinji far outweighed the gains. The fort had done its work. For seven years the three hills of Jinji had kept a large contigent of mughal forces occupied. It had eaten a deep hole into Mughal resources. Not only at Jinji, but the royal treasury was bleeding everywhere and was already under strain.

Jinji fell, but it did a big damage to the Mughal empire. The losses incurred in taking Jinji far outweighed the gains. The fort had done its work. For seven years the three hills of Jinji had kept a large contigent of mughal forces occupied. It had eaten a deep hole into Mughal resources. Not only at Jinji, but the royal treasury was bleeding everywhere and was already under strain.

Marathas would soon witness an unpleasant development, all of their own making. Dhanaji Jadhav and Santaji Ghorpade had a simmering rivalry, which was kept in check by the councilman Pralhad Niraji. But after Niraji’s death, Dhanaji grew bold and attacked Santaji. Nagoji Mane, one of Dhanaji’s men, killed Santaji. The news of Santaji’s death greatly encouraged Aurangzeb and Mughal army.

But by this time Mughals were no longer the army they were feared before. Aurangzeb, against advise of several of his experienced generals, kept the war on. It was much like Alexander on the borders of Taxila.

The Marathas again consolidated and the new Maratha counter offensive began. Rajaram made Dhanaji the next commander in chief. Maratha army was divided in three divisions. Dhanaji would himself lead the first division. Parshuram Timbak lead the second and Shankar Narayan lead the third. Dhanaji Jadhav defeated a large mughal force near Pandharpur. Shankar Narayan defeated Sarja Khan in Pune. Khanderao Dabhade, who lead a division under Dhanaji, took Baglan and Nashik. Nemaji Shinde, another commander with Shankar Narayan, scored a major victory at Nandurbar.

Enraged at this defeats, Aurangzeb himself took charge and launched another counter offensive. He laid siege to Panhala and attacked the fort of Satara. The seasoned commander, Prayagji Prabhu defended Satara for a good six months, but surrendered in April of 1700, just before onset of Monsoon. This foiled Aurangzeb’s strategy to clear as many forts before monsoon as possible.

In March of 1700, another bad news followed Marathas. Rajaram took his last breath. His queen Tarabai, who was also daughter of the gallant Maratha Commander-in-Chief Hambeerrao Mohite, took charge of Maratha army. Daughter of a braveheart, Tarabai proved her true mettle for the next seven years. She carried the struggle on with equal valor. Thus began the phase 3, the last phase of the prolonged war, with Marathas under the leadership of Tarabai.

In March of 1700, another bad news followed Marathas. Rajaram took his last breath. His queen Tarabai, who was also daughter of the gallant Maratha Commander-in-Chief Hambeerrao Mohite, took charge of Maratha army. Daughter of a braveheart, Tarabai proved her true mettle for the next seven years. She carried the struggle on with equal valor. Thus began the phase 3, the last phase of the prolonged war, with Marathas under the leadership of Tarabai.

The signs of strains were showing in Mughal camp in late 1701. Asad Khan, Julfikar Khan’s father, counselled Aurangzeb to end the war and turn around. This expedition had already taken a giant toll, much larger than originally planned, on Mughal empire. And serious signs were emerging that the 200 years old Mughal empire was crumbling and was in the middle of a war that was not winnable.

Mughals were bleeding heavily from treasuries. But Aurangzeb kept pressing the war on. When Tarabai took charge, Aurangzeb had laid siege to the fort of Parli (Sajjangad). Parshuram Trimbak defended the fort until monsoon and retreated quietly at the break of monsoon.The mughal army was dealt heavy loss by flash floods in the rivers around. These same tactics were followed by Marathas at the next stop of Aurangzeb, Panhala. Similar tactic was followed even for Vishalgad.

By 1704, Aurangzeb had Torana and Rajgad. He had won only a handful forts in this offensive, but he had spent several precious years. It was slowly dawning to him that after 24 years of constant war, he was no closer to defeating Marathas than he was the day he began.

The final Maratha counter offensive gathered momentum in North. Tarabai proved to be a valiant leader once again. One after another Mughal provinces fell in north. They were not in position to defend as the royal treasuries had been sucked dry and no armies were left in tow. In 1705, two Maratha army factions crossed Narmada. One under leadership of Nemaji Shinde hit as deep North as Bhopal. Second under the leadership of Dabhade struck Bharoch and West. Dabhade with his eight thousand men,attacked and defeated Mahomed khan’s forces numbering almost fourteen thousand. This left entire Gujarat coast wide open for Marathas. They immediately tightened their grip on Mughal supply chains.

In Maharashtra, Aurangzeb grew despondent. He started negotiations with Marathas, but cut abruptly and marched on a small kingdom called Wakinara. Naiks at Wakinara traced their lineage to royal family of Vijaynagar empire. They were never fond of Mughals and had sided with Marathas. Dhanaji marched into Sahyadris and won almost all the major forts back in short time. Satara and Parali forts were taken by Parshuram Timbak. Shankar Narayan took Sinhgad. Dhanaji then turned around and took his forces to Wakinara. He helped the Naiks at Wakinara sustain the fight. Naiks fought very bravely. Finally Wakinara fell, but the royal family of Naiks successfully escaped with least damage.

Aurangzeb had now given up all hopes and was now planning retreat to Burhanpur. Dhanaji Jadhav again fell on him and in swift and ferocious attack and dismantled the rear guard of his imperial army. Zulfikar Khan rescued the emperor and they successfully reached Burhanpur.

Aurangzeb witnessed bitter fights among his sons in his last days. Alone, lost, depressed, bankrupt, far away from home, he died sad death on 3rd March 1707. “I hope god will forgive me one day for my disastrous sins”, were his last words.

Thus ended a prolonged and grueling period in history of India. The Mughal kingdom fragmented and disintegrated soon after. And Deccan saw rise of a new sun, the Maratha empire.

[quote]” What some call the Muslim period in Indian history, was in reality a continuous war of occupiers against resisters, in which the Muslim rulers were finally defeated in the 18th century” Dr Koenraad Elst[/quote]

Reflection: Strategical Analysis:

In this war, Aurangzeb’s army totaled more than 500,000 in number (compared to total Maratha army in the ballpark of 150,000). With him he carried huge artillery, cavalry, muskettes, ammunition and giant wealth from royal treasuries to support this quest. This war by no means a fair game when numbers are considered.

In this war, Aurangzeb’s army totaled more than 500,000 in number (compared to total Maratha army in the ballpark of 150,000). With him he carried huge artillery, cavalry, muskettes, ammunition and giant wealth from royal treasuries to support this quest. This war by no means a fair game when numbers are considered.

The main features of Aurangzeb’s strategy were :-

Use of overwhelming force to demoralize the enemy –

This tactic had proved successful in Aurangzeb’s other missions. Thus he used this even in Maharashtra. On several occasions giant Mughal contigents were used to lay siege to a fort or capture a town.

Meticulously planned sieges to the forts –

Aurangzeb knew that the forts in Sahyadri formed backbone of Maratha defense. His calculation was to simply lay tight siege to the fort, demoralizing and starving the people inside and finally making them surrender the fort.

Aurangzeb knew that the forts in Sahyadri formed backbone of Maratha defense. His calculation was to simply lay tight siege to the fort, demoralizing and starving the people inside and finally making them surrender the fort.

Fork or pincer movements using large columns of infantry and cavalry –

With large number of infantry and cavalry, pincer could have proved effective and almost fatal against Marathas

Marathas had one advantage on their side, geography. They milked this advantage to the last bit. Their military activities were planned considering the terrain and the weather.

The main features of Maratha strategy were :-

Combined offensive-defensive strategy –

Throughout the war, Marathas never stopped their offensive. This served two purposes. The facts that Maratha army was carrying out offensive attacks in Mughal land suddenly made them psychologically equals to Mughals launching attack in Maratha land, even though Mughals were a much bigger force. This took negative toll on Mughal morale and boosted morale of their own men. Secondly, these offensive attacks in terms of quick raids often heavily damaged enemy supply chains taking toll on Mughal army. The forts formed backbone of Maratha defense. Thanks to Shivaji, the every fort had provision of fresh water. The total forts numbered almost 300 and this large number proved major headache to Aurangzeb.

Strategic fort defense –

Marathas had one big advantage on their side. They were the expert in fort warfare. The game of defense using forts had two components.

Marathas had one big advantage on their side. They were the expert in fort warfare. The game of defense using forts had two components.

First component was the right play of the strategic forts . In modern warfare, you have some strategic assets like aircraft carrier, presence of which needs a substantial change of plans on your enemy side. And then there are tactical assets, like tanks and large guns, which matter from battle to battle, but can be effectively countered by your enemy without making big plan changes. Similarly there are strategic forts, like Raigad, Janjira, Panhala and Jinji. Then there are number of tactical forts like Vishalgad, Sinhgad, Rajgad, etc.

Raigad, by its very nature, is large daunting fort. Built in 11th century by decedents of Mauryan Empire, it served as anchor to various kingdoms. Its cliffs sore high more than 1200 feet from base. It has abundant fresh water supply. Raigad, like Jinji could be defended for years at a stretch. No one could claim Sahyadri and Konkan as theirs without winning Raigad.

Aurangzeb knew difficulties in winning Raigad by war. So he managed to win it by using insider traitor, Suryaji Pisal. Had Marathas kept Raigad, Aurangzeb’s task would have been much tougher. Marathas lost Raigad early and could not win in back till much later. But they played the remaining two forts, Panhala and Jinji very well. Panhala is strategic because of its location on the confluence of multiple supply chains. Thus Marathas defended Panhala as long as they could and tried to win it back the earliest when they didn’t have it.

The second component of defensive fort warfare was matching the movements with weather. Forts are an asset in rest of the year, but are a liability in monsoon as it costs a lot to carry food and supplies up. Also the monsoon in coasts and ghats is severe in nature and no major military movement is possible. Thus Marathas often fought till Monsoon and surrendered the fort just before Monsoon. Before surrendering they burned all the food inside. Thus making it a proposition of loss in every way. Often times Marathas surrendered the fort empty, but later soon won it back filled with food and water. These events demoralized the enemy.

Offensive attacks in terms of evasive raids –

Marathas mostly launched offensive attacks in the region when Mughal army was away. They rarely engaged Mughal army in open fields till later part of the war. If situation seemed dire, they would retreat and disperse and thus conserve most of their men and arms for another day. The rivers Bhima, Krishna , Godavari and the mountains of Sahyadri, divide entire Maharashtra region is in several North- South corridors. When Mughal army traveled South through one corridor, Marathas would travel North through another and launch attacks there. This went on changing gradually and in the end, Maratha forces started engaging Mughals head on.

Marathas mostly launched offensive attacks in the region when Mughal army was away. They rarely engaged Mughal army in open fields till later part of the war. If situation seemed dire, they would retreat and disperse and thus conserve most of their men and arms for another day. The rivers Bhima, Krishna , Godavari and the mountains of Sahyadri, divide entire Maharashtra region is in several North- South corridors. When Mughal army traveled South through one corridor, Marathas would travel North through another and launch attacks there. This went on changing gradually and in the end, Maratha forces started engaging Mughals head on.

A noted historian Jadunath Sarkar makes an interesting observation. In his own words, “Aurangzeb won battle after battles, but in the end he lost the war. As the war prolonged, it transformed from war of weapons to war of spirits, and Aurangzeb was never able to break Maratha spirit.”

What Marathas did was an classic example of asymmetric defensive warfare. The statement above by Mr. Sarkar hides one interesting fact about this asymmetric defense. Is it really possible to lose most of the battles and still win the war?

The answer is yes, and explanation is a statistical phenomena called “Simpson’s paradox.”. According to Simpsons paradox, several micro-trends can lead to one conclusion, however a mega-trend combining all the micro-trends can lead to an exact opposite conclusion. Explanation is as follows.

Say two forces go on war, force A with 100 soldiers and force B with 40 soldiers. Now say in every battle between A and B, the following happens.

If A loses, they lose 80% of the soldiers fighting.

If B loses, they only lose 10% of the soldiers fighting.

If A wins, they lose 50% of the solders fighting.

If B wins, they lose only 10% of the soldiers fighting.

In the case above, the ratio of (resource drain of A / resource drain of B ) is higher than (initial number of A soldiers / initial number of B soldiers). So even if A wins battle more than 50% of the time, they will lose their resources faster and, in the end, will lose the war. All B has to do is keep the morale and keep the consistency.

One of the most famous warrior in ancient Indian history seems to agree with the conclusion above. In “Bhishma- perva” of Mahabharata, pitamah Bhishma begins the war-advice to king Yudhisthira with a famous quote –

“The strength of an army is not in its numbers’

For centuries , the mountains and valleys, towns and villages of Deccan had gotten used to being a pawn in the game of power. They changed hands as kingdoms warred with each other. They paid taxes whoever was in a position to extract them. For the most part they remained in a sleepy slumber, just turning and twisting in their bed.

Once in a while they sent their sons to fight in battles without ever asking why exactly the war is being launched. Other times they fought amongst themselves. They were divided, confused and did not have high hopes about their future.

This was the condition of Deccan when Shivaji launched his first expedition of fort Torana in 1645. By the time of his death mere 35 years later, he had transformed Deccan from a sleepy terrain to a thundering volcano.

Finally, here was a man whose vision of future was shared by a large general audience. An unmistakable characteristic of a modern concept of “nation-state”. Perhaps the most important factor that distinguishes Shivaji’s vision is that it was “unifying”. His vision went beyond building an army of proud warriors from warrior castes. It included people from all rungs of society sharing a common political idea and ready to defend it at any cost.+++

His vision went far beyond creating an empire for himself in Maharashtra. It included a building confederacy of states against what he thought were foreign invaders. He was trying to build an Alliance of Hindu kingdoms. He went out of his way to convince Mirza-Raje Jaisingh to leave Aurangzeb. He established relations with the dethroned royal family of Vijaynagar for whom he had tremendous respect. He attempted to unify the sparring Hindu power centers.

And they responded. Rajputs in Rajasthan, Nayaks in Karnataka, rulers of Mysore, the royal family of Vijaynagar were of valuable help to Shivaji and later to Marathas. It was certainly a step towards a nation getting its soul back.

While he was creating a political voice for Hindus, Muslims never faced persecution in his rule. Several Muslims served at high posts in his court and army. His personal body guard on his Agra visit was Muslim. His Naval officer, Siddi Hilal was Muslim. Thus Shivaji’s rule was not meant to challenge Islam as a personal religion, but it was a response to Political Islam.

It’s tempting for a Maharashtrian to claim the root of success of Marathas solely be in Maharashtra. But at the height of it’s peak, only 20% of Shivaji’s kingdom was part of Maharashtra. When Marathas launched northern campaigns in 18th century, it was even more less.

Soldiers in Maratha army came from diverse social and geographical backgrounds including from areas as far away as Kandahar to West and Bengal to East. Shivaji received a lot of support from various rulers and common people from all over India.

Thus limiting Marathas to Maharashtra is mostly a conclusion of a politician. It must be noted that the roots of Maharashtra culture can be traced to both ancient Karnataka and Northern India. Shivaji himself traced his lineage to Shisodia family of Rajputs. Maharashtrians should not be ashamed to admit that their roots lie elsewhere. In fact they should feel proud that land of Maharashtra is truly a melting pot where Southern and Northern Indian cultures melted to give birth to a new vision of a nation. Shivaji was far more an Indian king than a Maratha king.

Dear readers, here ends the story of an epic war. I hope this saga gives you a sense of realistic hope and a sense of humble pride. All you might be doing today is sitting in a cubicle for the day ,typing on keyboard. But remember that the same blood runs in our fingers that long long time ago displayed unparalleled courage and bravery, the same spirit resides within us that can once soured sky high upon the call of freedom.

by Kedar Soman

References:

“History of Mahrattas” by James Duff – http://www.archive.org/details/ahistorymahratt05duffgoog

“Shivaji and His Times” by Jadunath Sarkar – http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924024056750

“A History Of Maratha People” by Charles Kincaid – http://www.archive.org/details/historyofmaratha02kincuoft

“Background of Maratha Renaissance” by N. K. Behere – http://www.archive.org/details/backgroundofmara035242mbp

“Rise of The Maratha Power” by Mahadev Govind Ranade – http://www.archive.org/details/RiseOfTheMarathapower

“Maratha History” by S R Sharma – http://www.archive.org/details/marathahistory035360mbp

(visit the links to download the full books in PDF form free)

“Wonderous mystic, adventurous and intrepid, fortunate, roving

prince, with lovely and magnetic eyes, pleasing countenance,

winsome and polite,magnanimous to fallen foe like Alexander,

keen and a sharp intellect, quick in decision, ambitious conqueror

like Julius Caesar, given to action, resolute and strict

disciplinarian, expert strategist, far-sighted and constructive

statesman, brilliant organizer, who sagaciously countered his

political rivals and antagonists like the Mughals, Turks of Bijapur,

the Portuguese, the English, the Dutch, and the French. Undaunted

by the mighty Mughals, then the greatest power in Asia, Shivaji

fought the Bijapuris and carved out a grand Empire.”

-A.B. de Braganca Pereira says in “Arquivo Portugues Oriental, Vol

III”:

Mahratta mountain-woodO King Shivaji, Lighting thy brow, like a lightning flash,This thought descended,”Into one virtuous rule, this divided broken distracted India,I shall bind.”-Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore

Kasihki Kala Gayee, Mathura Masid Bhaee; Gar Shivaji Na Hoto,

To Sunati Hot Sabaki!(Kashi has lost its splendour, Mathura has become a mosque;

If Shivaji had not been, All would have been circumcised (converted)

– Kavi Bhushan (c. 1613-1712) was an Indian poet

(622721)

nAchChittvA para-marmANi nAkR^itvA karma dAruNam |

nAchChittvA para-marmANi nAkR^itvA karma dAruNam | Laid low by the prowess of the above gods, all people pay obeisance to them, but not all time to brahms or dhatri or pushan.

Laid low by the prowess of the above gods, all people pay obeisance to them, but not all time to brahms or dhatri or pushan. vidhAnaM deva-vihitaM tatra vidvAn na muhyati |

vidhAnaM deva-vihitaM tatra vidvAn na muhyati | okayAtrArtham eveha dharma-pravachanaM kR^itam |

okayAtrArtham eveha dharma-pravachanaM kR^itam |

Local scholars are still unsure about her identity, but what they do know is that this shrine’s unique roots lie not in China, but in far away south India. The deity, they say, was either brought to Quanzhou — a thriving port city that was at the centre of the region’s maritime commerce a few centuries ago — by Tamil traders who worked here some 800 years ago, or perhaps more likely, crafted by local sculptors at their behest.

Local scholars are still unsure about her identity, but what they do know is that this shrine’s unique roots lie not in China, but in far away south India. The deity, they say, was either brought to Quanzhou — a thriving port city that was at the centre of the region’s maritime commerce a few centuries ago — by Tamil traders who worked here some 800 years ago, or perhaps more likely, crafted by local sculptors at their behest.

First of all, the extent of the Harappan civilization. An important number of cities lie outside Pakistan, from the Afghan colony of Shortugai to a large number is Gujarat, including the port of Lothal, and another large number in India, including the metropolis of Rakhigarhi. Many of these cities are near the bed of the Saraswati in Haryana, which is why Indian archeologists are entitled to speak of “Sindhu-Saraswati civilization”. The emphasis on the Indus is the result of the first discoveries, viz. of Mohenjo Daro on and Harappa near the Indus, but is now dated. Note that this civilization was much larger than the contemporary Mesopotamian civilization. If we don’t look too closely on the map, with a Martian’s glance, we might say that its borders very roughly coincide with those of Pakistan.

First of all, the extent of the Harappan civilization. An important number of cities lie outside Pakistan, from the Afghan colony of Shortugai to a large number is Gujarat, including the port of Lothal, and another large number in India, including the metropolis of Rakhigarhi. Many of these cities are near the bed of the Saraswati in Haryana, which is why Indian archeologists are entitled to speak of “Sindhu-Saraswati civilization”. The emphasis on the Indus is the result of the first discoveries, viz. of Mohenjo Daro on and Harappa near the Indus, but is now dated. Note that this civilization was much larger than the contemporary Mesopotamian civilization. If we don’t look too closely on the map, with a Martian’s glance, we might say that its borders very roughly coincide with those of Pakistan. This conflicts with the orthodox Islamic calculation, upheld at the time of Partition by Maulana Azad, that (1) democracy is un-Islamic so that, like for the medieval Muslim invaders, power can just as well be obtained by a strong-headed minority, and that (2) in the longer run, the Muslims would obtain the majority in united India anyway, by means of conversions and a higher demographic growth. From the Islamic viewpoint, the history of Pakistan is not important because Pakistan is not important: it can only be a temporary tactic (and not even the best) on the way to the ultimate goal, viz. the Islamization of India. But in a confrontation with the infidels, anything un-Islamic becomes Islamic by being useful in the confrontation.

This conflicts with the orthodox Islamic calculation, upheld at the time of Partition by Maulana Azad, that (1) democracy is un-Islamic so that, like for the medieval Muslim invaders, power can just as well be obtained by a strong-headed minority, and that (2) in the longer run, the Muslims would obtain the majority in united India anyway, by means of conversions and a higher demographic growth. From the Islamic viewpoint, the history of Pakistan is not important because Pakistan is not important: it can only be a temporary tactic (and not even the best) on the way to the ultimate goal, viz. the Islamization of India. But in a confrontation with the infidels, anything un-Islamic becomes Islamic by being useful in the confrontation. As a historical claim, his thesis is largely untrue. For instance, the Gupta and Sikh empires clearly saddled this border, and one looks in vain for a historical kingdom coinciding with the Indus territory or with modern-day Pakistan. But the geological claim is of better quality. East Panjab and Kashmir constitute Indian parts of the Indus region (or is this a veiled Pakistani claim to these regions?), but further downstream, the border does roughly coincide with the watershed defining the Indus area. But is this watershed of political or civilizational relevance? The Aegean Sea separated Greece from Ionia, the Greek area of coastal Anatolia, yet the two areas were one in language and culture. Jinnah also didn’t base his Pakistan on this watershed: he would gladly have included the Nizam’s Hyderabad and did include East Bengal, part of the supposedly un-Pakistani Ganga plain.

As a historical claim, his thesis is largely untrue. For instance, the Gupta and Sikh empires clearly saddled this border, and one looks in vain for a historical kingdom coinciding with the Indus territory or with modern-day Pakistan. But the geological claim is of better quality. East Panjab and Kashmir constitute Indian parts of the Indus region (or is this a veiled Pakistani claim to these regions?), but further downstream, the border does roughly coincide with the watershed defining the Indus area. But is this watershed of political or civilizational relevance? The Aegean Sea separated Greece from Ionia, the Greek area of coastal Anatolia, yet the two areas were one in language and culture. Jinnah also didn’t base his Pakistan on this watershed: he would gladly have included the Nizam’s Hyderabad and did include East Bengal, part of the supposedly un-Pakistani Ganga plain. He is, however, right to identify the southern Pakistani province of Sindh with the Sumerian-attested name Meluhha. That this name is the origin of the word Mleccha indicates that its people were not embraced or held in high esteem in Vedic circles. And here we run into a phenomenon that Sufyan doesn’t realize yet, but that would certainly serve him well: the areas now constituting Pakistan and Afghanistan were considered inauspicious by the Vedic people. In his book The Rigveda and the Avesta (Delhi 2009), Shrikant Talageri describes how the Northwest was held in suspicion and taken to be the home of people who brought misfortune. In the Ramayana, exile and misery are visited upon Rama and Sita by the hand of Rama’s father’s second wife Kaikeyi, who hailed from the Northwest. In the Mahabharata, the war between the Pandava and Kaurava branches of the Bharata lineage is triggered by Pandu’s death, caused by his being enamoured of Madri, again a wife of Northwestern provenance. Talageri testifies how his own Brahmin family fasted by refraining from consuming Gangetic rice, while Panjab-grown grain was not deemed real food and hence was permitted. This information would marvelously fit in with Sufyan’s project.

He is, however, right to identify the southern Pakistani province of Sindh with the Sumerian-attested name Meluhha. That this name is the origin of the word Mleccha indicates that its people were not embraced or held in high esteem in Vedic circles. And here we run into a phenomenon that Sufyan doesn’t realize yet, but that would certainly serve him well: the areas now constituting Pakistan and Afghanistan were considered inauspicious by the Vedic people. In his book The Rigveda and the Avesta (Delhi 2009), Shrikant Talageri describes how the Northwest was held in suspicion and taken to be the home of people who brought misfortune. In the Ramayana, exile and misery are visited upon Rama and Sita by the hand of Rama’s father’s second wife Kaikeyi, who hailed from the Northwest. In the Mahabharata, the war between the Pandava and Kaurava branches of the Bharata lineage is triggered by Pandu’s death, caused by his being enamoured of Madri, again a wife of Northwestern provenance. Talageri testifies how his own Brahmin family fasted by refraining from consuming Gangetic rice, while Panjab-grown grain was not deemed real food and hence was permitted. This information would marvelously fit in with Sufyan’s project. The contrast between Harappa and Pakistan, or the fundamental Hinduness of the Harappans, is perhaps best illustrated with the three most famous artifacts from the Harappan civilization. The “priest-king” was probably a practitioner of the stellar cult suggested on many Harappan seal. The Quran emphatically forbids the Pagan worship of sun, moon and stars. At any rate, he was not a Muslim but a propagator of Paganism, the same kind against whom Mohammed made war. So, according to Islam, the state religion of Pakistan, the priest-king has been burning in hell for four thousand years. As for the “dancing-girl”, she exudes self-confidence and is stark naked. In today’s Pakistan, there would be no room for her. In fact, she would be stoned to death. Finally, the “Pashupati seal” may or may not depict Shiva as Lord of the Animals, but the character depicted would certainly feel more at home in a Hindu temple than in a mosque. A figure in a yoga posture clearly belongs in India more than in Pakistan. There is nothing Islamic and therefore nothing Pakistani about these three faces of the Indus civilization.

The contrast between Harappa and Pakistan, or the fundamental Hinduness of the Harappans, is perhaps best illustrated with the three most famous artifacts from the Harappan civilization. The “priest-king” was probably a practitioner of the stellar cult suggested on many Harappan seal. The Quran emphatically forbids the Pagan worship of sun, moon and stars. At any rate, he was not a Muslim but a propagator of Paganism, the same kind against whom Mohammed made war. So, according to Islam, the state religion of Pakistan, the priest-king has been burning in hell for four thousand years. As for the “dancing-girl”, she exudes self-confidence and is stark naked. In today’s Pakistan, there would be no room for her. In fact, she would be stoned to death. Finally, the “Pashupati seal” may or may not depict Shiva as Lord of the Animals, but the character depicted would certainly feel more at home in a Hindu temple than in a mosque. A figure in a yoga posture clearly belongs in India more than in Pakistan. There is nothing Islamic and therefore nothing Pakistani about these three faces of the Indus civilization.

The common denominator in all these costly mistakes was a lack of realism.

The common denominator in all these costly mistakes was a lack of realism. During his prayer meeting on 1 May 1947, he prepared the Hindus and Sikhs for the anticipated massacres of their kind in the upcoming state of Pakistan with these words: “I would tell the Hindus to face death cheerfully if the Muslims are out to kill them. I would be a real sinner if after being stabbed I wished in my last moment that my son should seek revenge. I must die without rancour. (*) You may turn round and ask whether all Hindus and all Sikhs should die. Yes, I would say. Such martyrdom will not be in vain.” (Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, vol.LXXXVII, p.394-5) It is left unexplained what purpose would be served by this senseless and avoidable surrender to murder.

During his prayer meeting on 1 May 1947, he prepared the Hindus and Sikhs for the anticipated massacres of their kind in the upcoming state of Pakistan with these words: “I would tell the Hindus to face death cheerfully if the Muslims are out to kill them. I would be a real sinner if after being stabbed I wished in my last moment that my son should seek revenge. I must die without rancour. (*) You may turn round and ask whether all Hindus and all Sikhs should die. Yes, I would say. Such martyrdom will not be in vain.” (Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, vol.LXXXVII, p.394-5) It is left unexplained what purpose would be served by this senseless and avoidable surrender to murder. So, he was dismissing as cowards those who saved their lives fleeing the massacre by a vastly stronger enemy, viz. the Pakistani population and security forces. But is it cowardice to flee a no-win situation, so as to live and perhaps to fight another day? There can be a come-back from exile, not from death. Is it not better to continue life as a non-Lahorite than to cling to one’s location in Lahore even if it has to be as a corpse? Why should staying in a mere location be so superior to staying alive? To be sure, it would have been even better if Hindus could have continued to live with honour in Lahore, but Gandhi himself had refused to use his power in that cause, viz. averting Partition. He probably would have found that, like the butchered or fleeing Hindus, he was no match for the determination of the Muslim League, but at least he could have tried. In the advice he now gave, the whole idea of non-violent struggle got perverted.

So, he was dismissing as cowards those who saved their lives fleeing the massacre by a vastly stronger enemy, viz. the Pakistani population and security forces. But is it cowardice to flee a no-win situation, so as to live and perhaps to fight another day? There can be a come-back from exile, not from death. Is it not better to continue life as a non-Lahorite than to cling to one’s location in Lahore even if it has to be as a corpse? Why should staying in a mere location be so superior to staying alive? To be sure, it would have been even better if Hindus could have continued to live with honour in Lahore, but Gandhi himself had refused to use his power in that cause, viz. averting Partition. He probably would have found that, like the butchered or fleeing Hindus, he was no match for the determination of the Muslim League, but at least he could have tried. In the advice he now gave, the whole idea of non-violent struggle got perverted. t cannot be denied that Gandhian non-violence has a few successes to its credit. But these were achieved under particularly favourable circumstances: the stakes weren’t very high and the opponents weren’t too foreign to Gandhi’s ethical standards. In South Africa, he had to deal with liberal British authorities who weren’t affected too seriously in their power and authority by conceding Gandhi’s demands. Upgrading the status of the small Indian minority from equality with the Blacks to an in-between status approaching that of the Whites made no real difference to the ruling class, so Gandhi’s agitation was rewarded with some concessions. Even in India, the stakes were never really high. Gandhi’s Salt March made the British rescind the Salt Tax, a limited financial price to pay for restoring native acquiescence in British paramountcy, but he never made them concede Independence or even Home Rule with a non-violent agitation. The one time he had started such an agitation, viz. in 1930-31, he himself stopped it in exchange for a few small concessions.

t cannot be denied that Gandhian non-violence has a few successes to its credit. But these were achieved under particularly favourable circumstances: the stakes weren’t very high and the opponents weren’t too foreign to Gandhi’s ethical standards. In South Africa, he had to deal with liberal British authorities who weren’t affected too seriously in their power and authority by conceding Gandhi’s demands. Upgrading the status of the small Indian minority from equality with the Blacks to an in-between status approaching that of the Whites made no real difference to the ruling class, so Gandhi’s agitation was rewarded with some concessions. Even in India, the stakes were never really high. Gandhi’s Salt March made the British rescind the Salt Tax, a limited financial price to pay for restoring native acquiescence in British paramountcy, but he never made them concede Independence or even Home Rule with a non-violent agitation. The one time he had started such an agitation, viz. in 1930-31, he himself stopped it in exchange for a few small concessions. The ethical framework limiting the use of force to a minimum is known as “just war theory”, developed by European thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas and Hugo Grotius between the 13

The ethical framework limiting the use of force to a minimum is known as “just war theory”, developed by European thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas and Hugo Grotius between the 13

S.N. Balagangadhara, better known as Balu, is Professor of Comparative Culture Studies in Ghent University, Belgium. Balu is a Kannadiga Brahmin by birth, a former Marxist, and his discourse has a very in-your-face quality. In his latest book, Reconceptualizing India Studies (Oxford University Press 2012), the attentive reader will see a critique of the Indological establishment in the West and the political and cultural establishment in India. Like Rajiv Malhotra’s recent works, it questions their legitimacy. The reigning Indologists and India-watchers would do well to read it.

S.N. Balagangadhara, better known as Balu, is Professor of Comparative Culture Studies in Ghent University, Belgium. Balu is a Kannadiga Brahmin by birth, a former Marxist, and his discourse has a very in-your-face quality. In his latest book, Reconceptualizing India Studies (Oxford University Press 2012), the attentive reader will see a critique of the Indological establishment in the West and the political and cultural establishment in India. Like Rajiv Malhotra’s recent works, it questions their legitimacy. The reigning Indologists and India-watchers would do well to read it.

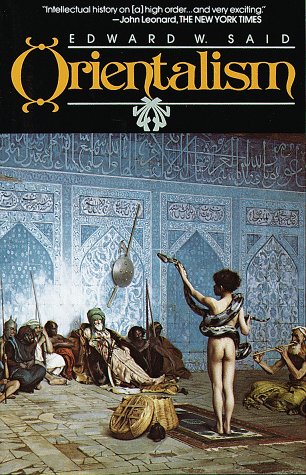

Look at the secularists, who for decades now have gone gaga over Said’s concept of Orientalism: “Orientalism is reproduced in the name of a critique of Orientalism. It is completely irrelevant whether one uses a Marx, a Weber or a Max Müller to do so. (…) the result is the same: uninteresting trivia, as far as the growth of human knowledge is concerned; but pernicious in its effect as far as Indian intellectuals are concerned.” (p.47) India has produced intellectual giants like (limiting ourselves to the 20th century:) R.C. Majumdar, P.V. Kane or A.K. Coomaraswamy, but the Indian secularists are intellectually very poor copies of their Western role models.

Look at the secularists, who for decades now have gone gaga over Said’s concept of Orientalism: “Orientalism is reproduced in the name of a critique of Orientalism. It is completely irrelevant whether one uses a Marx, a Weber or a Max Müller to do so. (…) the result is the same: uninteresting trivia, as far as the growth of human knowledge is concerned; but pernicious in its effect as far as Indian intellectuals are concerned.” (p.47) India has produced intellectual giants like (limiting ourselves to the 20th century:) R.C. Majumdar, P.V. Kane or A.K. Coomaraswamy, but the Indian secularists are intellectually very poor copies of their Western role models. Balu’s explanation of intercommunal relations in India and the state’s role therein is original and clear. In his opinion, the secular state is not there to curb religious violence, but is in fact the cause of this violence. He focuses on its position in the question of religious conversion, which is forbidden in some neighbouring countries and demanded to be forbidden by many Hindus (both Mahatma Gandhi and the Hindu nationalists). But it is upheld as a right by the Muslims and especially by the Christian missionaries — and by the “secular” state. The latter clearly takes a partisan stand in doing so; and it would also be partisan if it did the opposite. It is impossible to be impartisan.

Balu’s explanation of intercommunal relations in India and the state’s role therein is original and clear. In his opinion, the secular state is not there to curb religious violence, but is in fact the cause of this violence. He focuses on its position in the question of religious conversion, which is forbidden in some neighbouring countries and demanded to be forbidden by many Hindus (both Mahatma Gandhi and the Hindu nationalists). But it is upheld as a right by the Muslims and especially by the Christian missionaries — and by the “secular” state. The latter clearly takes a partisan stand in doing so; and it would also be partisan if it did the opposite. It is impossible to be impartisan. The whole “secular” discourse on “religion” and intercommunal relations is borrowed from Christianity. The basic framework to think about religion is informed by Western experiences and fails to see the radical difference between these and the native traditions: “the secular state assumes that the Semitic religions and the Hindu traditions are instances of the same kind” (p.203). In realities, Hindus and Parsis don’t missionize and refrain from basing their religions on a defining truth claim. By contrast, Christianity and Islam believe they offer the truth, and consequently want everyone to accept it.

The whole “secular” discourse on “religion” and intercommunal relations is borrowed from Christianity. The basic framework to think about religion is informed by Western experiences and fails to see the radical difference between these and the native traditions: “the secular state assumes that the Semitic religions and the Hindu traditions are instances of the same kind” (p.203). In realities, Hindus and Parsis don’t missionize and refrain from basing their religions on a defining truth claim. By contrast, Christianity and Islam believe they offer the truth, and consequently want everyone to accept it.

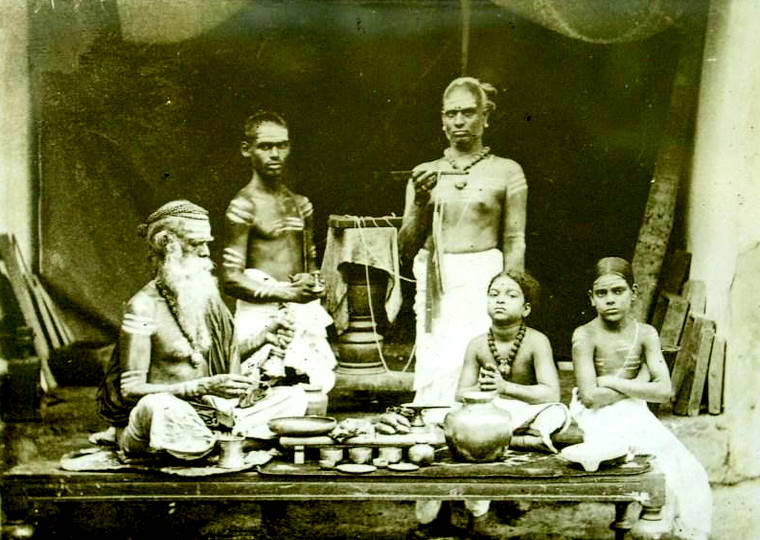

Within the Portuguese territories, physical persecution of Paganism naturally hit the Brahmins hardest. Treaties with Hindu kings had to stipulate explicitly that the Portuguese must not kill Brahmins. But in the case of Christian anti-Brahminism, these physical persecutions were a small matter compared to the systematic ideological and propagandistic attack on Brahminism, which has conditioned the views of many non-missionaries and has by now been amplified enormously because Secularists, Akalis, Marxists and Muslims have joined the chorus. In fact, apart from anti-Judaism, the anti-Brahmin campaign started by the missionaries is the biggest vilification campaign in world history (emphasis added).

Within the Portuguese territories, physical persecution of Paganism naturally hit the Brahmins hardest. Treaties with Hindu kings had to stipulate explicitly that the Portuguese must not kill Brahmins. But in the case of Christian anti-Brahminism, these physical persecutions were a small matter compared to the systematic ideological and propagandistic attack on Brahminism, which has conditioned the views of many non-missionaries and has by now been amplified enormously because Secularists, Akalis, Marxists and Muslims have joined the chorus. In fact, apart from anti-Judaism, the anti-Brahmin campaign started by the missionaries is the biggest vilification campaign in world history (emphasis added). De Nobili’s approach was one possible application of the Jesuits larger strategy, which aimed at converting the elite in the hope that they would carry the masses with them. This approach had been tried in vain in China, in Japan, and even at the Moghul court (today, it is finally meeting with a measure of success in South Korea). A practical implication of this strategy was that Christianity had to be presented as a noble and elitist religion. This came naturally to the Jesuits, who (unlike, for instance, the Franciscans) styled themselves as an elite order.

De Nobili’s approach was one possible application of the Jesuits larger strategy, which aimed at converting the elite in the hope that they would carry the masses with them. This approach had been tried in vain in China, in Japan, and even at the Moghul court (today, it is finally meeting with a measure of success in South Korea). A practical implication of this strategy was that Christianity had to be presented as a noble and elitist religion. This came naturally to the Jesuits, who (unlike, for instance, the Franciscans) styled themselves as an elite order. It is therefore not true that the Church’s motivation in blackening the Brahmins had anything to do with a concern for equality. The Church was against equality in the first place, and even when equality became the irresistible fashion, the Church allowed caste inequality to continue wherever it considered it opportune to do so. As a missionary has admitted to me: in Goa, many churches still have separate doors for high-caste and low-caste people, and caste discrimination at many levels is still widespread. Commenting on the persistence of caste distinctions in the Church, a Dalit convert told me: I feel like a frog who has jumped from one muddy pool into another pool just as muddy.

It is therefore not true that the Church’s motivation in blackening the Brahmins had anything to do with a concern for equality. The Church was against equality in the first place, and even when equality became the irresistible fashion, the Church allowed caste inequality to continue wherever it considered it opportune to do so. As a missionary has admitted to me: in Goa, many churches still have separate doors for high-caste and low-caste people, and caste discrimination at many levels is still widespread. Commenting on the persistence of caste distinctions in the Church, a Dalit convert told me: I feel like a frog who has jumped from one muddy pool into another pool just as muddy. In the past century, the Churches one after another came around to the decision that the lower ranks of society should be made the prime target of conversion campaigns. Finding that the conversion of the high-caste people was not getting anywhere, they settled for the low-castes and tribals, and adapted their own image accordingly. One implication was that the Brahmins were no longer just the guardians of Paganism, but also the antipodes of the low-castes on the caste ladder. A totally new line of propaganda was launched: Brahmins were the oppressors of the low-caste people.

In the past century, the Churches one after another came around to the decision that the lower ranks of society should be made the prime target of conversion campaigns. Finding that the conversion of the high-caste people was not getting anywhere, they settled for the low-castes and tribals, and adapted their own image accordingly. One implication was that the Brahmins were no longer just the guardians of Paganism, but also the antipodes of the low-castes on the caste ladder. A totally new line of propaganda was launched: Brahmins were the oppressors of the low-caste people. Then again, the Aryan Invasion theory was the alpha and omega of the version of India history spread by anti-Brahminism.[5] Phule’s book Slavery starts out with this view of history: “Recent researches have shown beyond a shadow of a doubt that the Brahmins were not the Aborigines of India…. Aryans came to India not as simple emigrants with peaceful intentions of colonisation, but as conquerors. They appear to have been a race imbued with very high notions of self, extremely cunning, arrogant and bigoted.”

Then again, the Aryan Invasion theory was the alpha and omega of the version of India history spread by anti-Brahminism.[5] Phule’s book Slavery starts out with this view of history: “Recent researches have shown beyond a shadow of a doubt that the Brahmins were not the Aborigines of India…. Aryans came to India not as simple emigrants with peaceful intentions of colonisation, but as conquerors. They appear to have been a race imbued with very high notions of self, extremely cunning, arrogant and bigoted.” Even among the champions of the Hindu cause, anti-Brahminism acquired a following. The Hindu reform movement Arya Samaj rejected Brahminism and its heretical brainchildren, idolatry and the caste system, as utterly non-Vedic. Brahmin temples were desecrated in the name of Hinduism. Orthodox Brahmins were attacked as the traitors of Hindu interests.

Even among the champions of the Hindu cause, anti-Brahminism acquired a following. The Hindu reform movement Arya Samaj rejected Brahminism and its heretical brainchildren, idolatry and the caste system, as utterly non-Vedic. Brahmin temples were desecrated in the name of Hinduism. Orthodox Brahmins were attacked as the traitors of Hindu interests.

Founded in 1875, the Ârya Samâj, in effect “Society of Vedicists”, was a trail-blazer of Hindu revivalism and anti-colonial nationalism until Independence. It worked bravely for the reconversion of Indian Muslims, the only humane solution to India’s communal problem. Some of its spokesmen gave their lives for speaking out on Islam, most notably Pandit Lekhram in 1897 and Swami Shraddahananda (co-founder of the Hindu Mahasabha) in 1926.

Founded in 1875, the Ârya Samâj, in effect “Society of Vedicists”, was a trail-blazer of Hindu revivalism and anti-colonial nationalism until Independence. It worked bravely for the reconversion of Indian Muslims, the only humane solution to India’s communal problem. Some of its spokesmen gave their lives for speaking out on Islam, most notably Pandit Lekhram in 1897 and Swami Shraddahananda (co-founder of the Hindu Mahasabha) in 1926. As an organization, the Arya Samaj is no longer very powerful or important, but its message has spread far and wide in educated Hindu society. The same is even more true of a similar movement, the Brahmo Samaj (°1825), a flagbearer of the Bengal renaissance which tried to translate Hinduism into rational-sounding concepts acceptable to the British colonizers and the first circles of anglicized Hindus.Whereas the Arya Samaj embraced a Christian-like religious theism, the Brahmo Samaj tended more towards a modern Enlightenment-inspired deism, i.e. the philosophical acceptance of a distant cosmic intelligence rather than a personal God biddable by human imprecations and sacrifices. But like the Aryas, the Brahmos rejected Hindu polytheism as a degenerate aberration from the true Vedic spirit.

As an organization, the Arya Samaj is no longer very powerful or important, but its message has spread far and wide in educated Hindu society. The same is even more true of a similar movement, the Brahmo Samaj (°1825), a flagbearer of the Bengal renaissance which tried to translate Hinduism into rational-sounding concepts acceptable to the British colonizers and the first circles of anglicized Hindus.Whereas the Arya Samaj embraced a Christian-like religious theism, the Brahmo Samaj tended more towards a modern Enlightenment-inspired deism, i.e. the philosophical acceptance of a distant cosmic intelligence rather than a personal God biddable by human imprecations and sacrifices. But like the Aryas, the Brahmos rejected Hindu polytheism as a degenerate aberration from the true Vedic spirit.

It is undeniable that Hindu Maha Sabha ideologue Savarkar spoke of reviving the “race spirit” of the Hindus. So did Golwalkar. Sri Aurobindo even used the term “Aryan race”, which to him meant exactly the same thing as “Hindu nation”,

It is undeniable that Hindu Maha Sabha ideologue Savarkar spoke of reviving the “race spirit” of the Hindus. So did Golwalkar. Sri Aurobindo even used the term “Aryan race”, which to him meant exactly the same thing as “Hindu nation”,  After 1945, the English language gradually lost the usage of the term “race” for the concept of “nation”; the Hindu nationalists followed suit. This was only natural: they had never cared for “race” in the biological sense so dear to the Nazis. The very concept of race, having been narrowed down to its biological meaning, has simply disappeared from their horizon. It is plainly untrue that Hindu ideologues at any time have shared Hitler’s racism.

After 1945, the English language gradually lost the usage of the term “race” for the concept of “nation”; the Hindu nationalists followed suit. This was only natural: they had never cared for “race” in the biological sense so dear to the Nazis. The very concept of race, having been narrowed down to its biological meaning, has simply disappeared from their horizon. It is plainly untrue that Hindu ideologues at any time have shared Hitler’s racism. Most secularists pretend not to know this unambiguous position of Savarkar’s (in many cases, they really don’t know, for Hindu-baiting is usually done without reference to primary sources). Likewise, Savarkar’s plea for caste intermarriage to promote the oneness of Hindu society is usually ignored in order to keep up the pretence that he was a reactionary on caste, an “upper-caste racist” (as Gyan Pandey puts it), and what not. There are no limits to secularist dishonesty, and so we are glad to find at least one voice in their crowd which does acknowledge these positions of Savarkar’s.

Most secularists pretend not to know this unambiguous position of Savarkar’s (in many cases, they really don’t know, for Hindu-baiting is usually done without reference to primary sources). Likewise, Savarkar’s plea for caste intermarriage to promote the oneness of Hindu society is usually ignored in order to keep up the pretence that he was a reactionary on caste, an “upper-caste racist” (as Gyan Pandey puts it), and what not. There are no limits to secularist dishonesty, and so we are glad to find at least one voice in their crowd which does acknowledge these positions of Savarkar’s. The first point rightly acknowledges that Savarkar, not being a historian, accepted the Aryan invasion theory promoted by prestigious seats of Western learning; and that he saw modern Hindus as a biological and cultural mixture of Aryan invaders and indigenous non-Aryans. He shared this view with Indian authors across the political spectrum, e.g. with Jawaharlal Nehru. Like Nehru, he saw no reason why people of diverse biological origins would be unable to form a united nation; the difference being that Nehru saw this unification as a project just started (“India, a nation in the making”), while Savarkar believed that this unification had come about in the distant past already.

The first point rightly acknowledges that Savarkar, not being a historian, accepted the Aryan invasion theory promoted by prestigious seats of Western learning; and that he saw modern Hindus as a biological and cultural mixture of Aryan invaders and indigenous non-Aryans. He shared this view with Indian authors across the political spectrum, e.g. with Jawaharlal Nehru. Like Nehru, he saw no reason why people of diverse biological origins would be unable to form a united nation; the difference being that Nehru saw this unification as a project just started (“India, a nation in the making”), while Savarkar believed that this unification had come about in the distant past already. Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke has written a book on the strange case of a French-Greek lady who converted to Hinduism and later went on to work for the neo-Nazi cause, Maximiani Portas a.k.a. Savitri Devi. The book is generally of high scholarly quality and full of interesting detail, but when it comes to Indian politics, the author is woefully misinformed by his less than impartisan sources.

Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke has written a book on the strange case of a French-Greek lady who converted to Hinduism and later went on to work for the neo-Nazi cause, Maximiani Portas a.k.a. Savitri Devi. The book is generally of high scholarly quality and full of interesting detail, but when it comes to Indian politics, the author is woefully misinformed by his less than impartisan sources. If one is inclined towards fascism, and one has the good fortune to live at the very moment of fascism’s apogee, it seems logical that one would seize the opportunity and join hands with fascism while the time is right. Conversely, if one has the opportunity to join hands with fascism but refrains from doing so, this is a strong indication that one is not that “fascist” after all. Many Hindu leaders and thinkers were sufficiently aware of the world situation in the second quarter of the twentieth century; what was their position vis-a-vis the Axis powers?

If one is inclined towards fascism, and one has the good fortune to live at the very moment of fascism’s apogee, it seems logical that one would seize the opportunity and join hands with fascism while the time is right. Conversely, if one has the opportunity to join hands with fascism but refrains from doing so, this is a strong indication that one is not that “fascist” after all. Many Hindu leaders and thinkers were sufficiently aware of the world situation in the second quarter of the twentieth century; what was their position vis-a-vis the Axis powers? And indeed, in the successful retreat from Dunkirk and in the British victories in North Africa and Iraq, Indian troops played a decisive role. It would earn the Hindus the gratitude of the British, or at least their respect. And if not that, it would instill the beginnings of fear in the minds of the British rulers: it would offer military training and experience to the Hindus, on a scale where the British could not hope to contain an eventual rebellion in the ranks. After the war, even without having to organize an army of their own, they would find themselves in a position where the British could not refuse them their independence.

And indeed, in the successful retreat from Dunkirk and in the British victories in North Africa and Iraq, Indian troops played a decisive role. It would earn the Hindus the gratitude of the British, or at least their respect. And if not that, it would instill the beginnings of fear in the minds of the British rulers: it would offer military training and experience to the Hindus, on a scale where the British could not hope to contain an eventual rebellion in the ranks. After the war, even without having to organize an army of their own, they would find themselves in a position where the British could not refuse them their independence. It is not unreasonable to suggest that Savarkar’s collaboration with the British against the Axis was opportunistic. He was not in favour of any foreign power, be it Britain, the US, the Soviet Union, Japan or Germany. He simply chose the course of action that seemed the most useful for the Hindu nation. But the point is: he could have opted for collaboration with the Axis, he could have calculated that a Hindu-Japanese combine would be unbeatable, he could even have given his ideological support to the Axis, but he did not. The foremost Hindutva ideologue, president of what was then the foremost political Hindu organization, supported the Allied war effort against the Axis.