The dialogue which Raja Ram Mohun Roy had started in the third decade of the nineteenth century stopped abruptly with the passing away of Mahatma Gandhi in January 1948. The Hindu leadership or what passed for it in post-independence India was neither equipped for nor interested in the battle for men’s minds. It believed in ‘organising’ the Hindus without bothering about what they carried inside their heads. It neither knew nor cared to know what Hinduism stood for. Its history of India began with the advent of the Islamic invaders. The spiritual traditions, ways of worship, scriptures and thought systems of pre-Islamic India were beyond its mental horizon.

The dialogue which Raja Ram Mohun Roy had started in the third decade of the nineteenth century stopped abruptly with the passing away of Mahatma Gandhi in January 1948. The Hindu leadership or what passed for it in post-independence India was neither equipped for nor interested in the battle for men’s minds. It believed in ‘organising’ the Hindus without bothering about what they carried inside their heads. It neither knew nor cared to know what Hinduism stood for. Its history of India began with the advent of the Islamic invaders. The spiritual traditions, ways of worship, scriptures and thought systems of pre-Islamic India were beyond its mental horizon.

The Christian missions, as we have seen, had never had it so good. Unchallenged ideologically, they broke out of the tight corner in which Mahatma Gandhi had put them and resumed the monologue which had characterised them in the pre-dialogue period. A number of mission strategies were dressed up as ‘theologies in the Indian context’. The core of the Christian dogma remained intact, namely, that Jesus Christ was the only saviour. The language of presenting the dogma, however, underwent what looked like a radical change to the unwary Hindus, particularly those in search of a ‘synthesis of all faiths’.

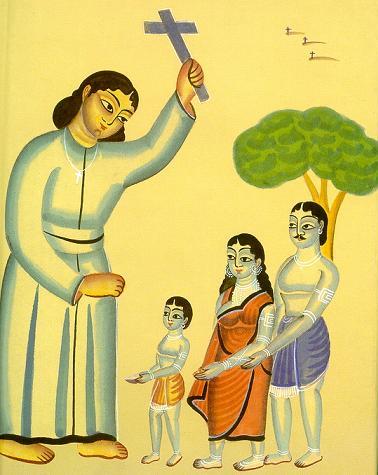

In the days of old, the missions had denounced Hinduism as devil-worship and made it their business to save the Hindus from the everlasting fire of hell. Now they abandoned that straight-forward stance. In the new language that was adopted, Hinduism was made a beneficiary of the Cosmic Revelation that had preceded Jehovah’s Covenant with Moses. Hinduism was also credited with an unceasing quest for the ‘True One God’. The business of the missions was to direct that quest towards Christ who was ‘hidden in Hinduism’ and thereby make them co-sharers in the final Covenant which Jesus had scaled with his blood. That was the Theology of Fulfilment. A number of learned treatises were turned out on the subject. The labour invested was perhaps praise-worthy. The purpose, however, was deliberately dishonest.

In the days of old, Hindu culture like Hindu religion was a creation of the devil. It had to be scrapped and the stage swept clean for the culture of Christianity to take over. In the new language, Hindu culture was credited with great creations in philosophy, literature, art, architecture, music, painting and the rest. There was reservation only at one point. This culture, it was said, had stopped short of reaching the crest because its spiritual perceptions were deficient, even defective. It could surge forward on its aborted journey only by becoming a willing vehicle for ‘Christian truths’.

In the days of old, Hindu culture like Hindu religion was a creation of the devil. It had to be scrapped and the stage swept clean for the culture of Christianity to take over. In the new language, Hindu culture was credited with great creations in philosophy, literature, art, architecture, music, painting and the rest. There was reservation only at one point. This culture, it was said, had stopped short of reaching the crest because its spiritual perceptions were deficient, even defective. It could surge forward on its aborted journey only by becoming a willing vehicle for ‘Christian truths’.

That was the Theology of Inculturation or Indigenisation. It created another lot of literature. The missions, however, did not stop at the theoretical proposition. They demonstrated practically how Hindu culture should serve Jesus. Christ. A chain of Christian Ashrams sprang up all over the country. A number of Christian missionaries started masquerading as Hindu sannyasins, wearing the ochre robe, eating vegetarian food, sleeping on the floor and worshipping with the accoutrements of Hindu pUjA. The sacrifice they made of comforts in the mission stations and monasteries was perhaps admirable. The purpose of the exercise, however, was perfidious.

The controllers of the missions were not exactly happy when they found that Communism was proving more attractive than Christianity for some of the missionaries. Marxism was in the air and it was difficult to dissuade some theologians and field workers from seeing a social revolutionary in Jesus. So the controllers did what they thought to be the next best thing. They encouraged the hot-heads to hammer out another theology, complete with class struggle and the rest, and hurl it against the ‘oppressive social system sanctioned by Hinduism’.

It became the business of the Christian missions to help the ‘have-nots of Hindu society’ rise in revolt against their ‘oppressors’. Hindu society was found to be brimful of caste discrimination, class coercion, degradation of women, neglect of children, untouchability, bonded labour, and so on. That was the Theology of Liberation. It also produced some literature. Malcontents from among the Hindus were hired to lend their names as authors. Never mind if the pamphlets were poorly written and badly printed. The pretence that they came from the ‘deprived and the down-trodden section of Hindu society’ had to be maintained.

The Christian press presented the quibbles among these competing theologies as if momentous matters were being discussed. Hindus were left with the impression that the house of Christianity stood divided from within. The controllers of the missions, however, had everything under control. They were experimenting with various strategies in order to find out which was likely to yield the best results in the long run. In any case, different strategies could be employed simultaneously by different flanks of the missionary phalanx. Each Hindu who came in contact with them could be served with the theology which suited his or her taste.

The Christian press presented the quibbles among these competing theologies as if momentous matters were being discussed. Hindus were left with the impression that the house of Christianity stood divided from within. The controllers of the missions, however, had everything under control. They were experimenting with various strategies in order to find out which was likely to yield the best results in the long run. In any case, different strategies could be employed simultaneously by different flanks of the missionary phalanx. Each Hindu who came in contact with them could be served with the theology which suited his or her taste.

What helped the Christian missions a good deal from the outside was the rise of Nehruvian Secularism as India’s state policy as well as a raging fashion among India’s intellectual elite. The knowledgeable among the missionaries were surprised and somewhat amused. They knew that Secularism had risen in the West as the deadliest enemy of Christian dogmas and that it had deprived the churches of their stranglehold on state power.

In India, however, Secularism was providing a smokescreen behind which Christianity could steal a march. Politicians of all parties including parties which passed as Hindu, leading journalists and academicians, and scribes of all sorts saw the spectre of ‘Hindu communalism’ whenever someone raised a voice, howsoever feeble and apologetic, about the foreign finances and subversive activities of the Christian missions.

In India, however, Secularism was providing a smokescreen behind which Christianity could steal a march. Politicians of all parties including parties which passed as Hindu, leading journalists and academicians, and scribes of all sorts saw the spectre of ‘Hindu communalism’ whenever someone raised a voice, howsoever feeble and apologetic, about the foreign finances and subversive activities of the Christian missions.

An informed critique of Christianity invited angry snarls from the same quarters. The missions did not feel quite comfortable with the guardians of India’s Secularism; there were too many goddamned Communists, Royists, Socialists and Leftists of all sorts in that crowd. But that was a problem to be faced in the long run. In the short run, the deep hostility which Secularism in India entertained for Hinduism could be turned to Christianity’s advantage. At the same time, Hindus could be frightened into entering a ‘united front of all religions against the forces of Godless materialism’.

Mahatma Gandhi’s sarva-dharma-sambhAva was providing grist to the same mill. The old man had tried to cure Christianity of its exclusiveness and sense of superiority. That was the substance of his objection to proselytisation. He had advised Christians in general and Christian missionaries in particular to be busy with their own moral and spiritual improvement rather than with the salvation of Hindus.

Mahatma Gandhi’s sarva-dharma-sambhAva was providing grist to the same mill. The old man had tried to cure Christianity of its exclusiveness and sense of superiority. That was the substance of his objection to proselytisation. He had advised Christians in general and Christian missionaries in particular to be busy with their own moral and spiritual improvement rather than with the salvation of Hindus.

In his own days, Christian theologians had resented his doctrine of sarva-dharma-samabhAva and repudiated it as destructive of the very basis of Christianity. But now that the doctrine had been turned into a mindless slogan by the Mahatma’s own disciples and handed over to the watchdogs of Nehruvian Secularism as another bark against Hinduism, it was safeguarding Christianity’s right to multiply its missions. The doubting Thomases among the Hindus could be told that Bapu stood for equality of all religions and their opportunity to flourish without let or hindrance.

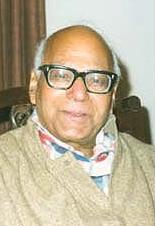

This was the atmosphere in which Ram Swarup’s book, ‘The Word As Revelation: Names of Gods, ?, came out of the press. He had invested in it many years of meditation and reflection. Its subject was neither Christianity, nor its missions.

On the contrary, it was an attempt at understanding the spiritual consciousness which had manifested itself in a multiplicity of Gods, not only in India but in many other lands. Christianity came in for a brief examination when he evaluated Monotheism from the standpoint of the spiritual vision which has sustained religious pluralism among the Hindus down to the present day. But the premises from which he would subsequently develop his deeper critique of Christianity became clear in this book.

On the contrary, it was an attempt at understanding the spiritual consciousness which had manifested itself in a multiplicity of Gods, not only in India but in many other lands. Christianity came in for a brief examination when he evaluated Monotheism from the standpoint of the spiritual vision which has sustained religious pluralism among the Hindus down to the present day. But the premises from which he would subsequently develop his deeper critique of Christianity became clear in this book.

Before we take up Ram Swarup’s critique of Christianity in some detail, it would be helpful if we survey briefly the history of how Monotheism came to India and how it acquired the prestige it enjoys at present in the eyes of the dominant and vocal section of the Hindu intelligentsia. It is not rarely that one meets Hindu thinkers who regard Monotheism as a distinct and major contribution made to religious thought by Christianity and Islam.

Many Hindu thinkers disown as relics from a primitive past the multiplicity of Gods for which Hinduism is well known; they also denounce idol worship round which Hinduism has remained centred down the ages. Even those Hindu thinkers who do not disown the Hindu pantheon, consign it to an inferior status vis-a-vis the Great God who is ‘One without a second’; if they defend idol worship, they do so only as a device meant for the spiritually underdeveloped’ seekers who are supposed to be incapable of viewing God without the aid of visible forms.

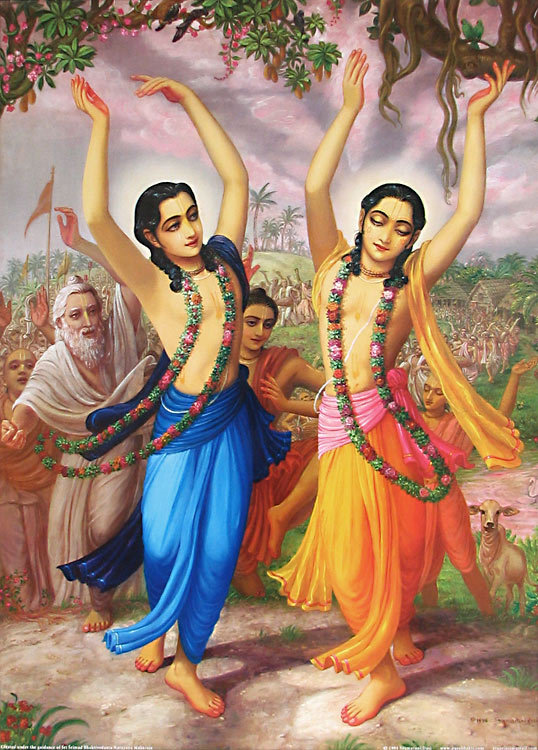

Monotheism was unknown to Hinduism in ancient times, either as a religious doctrine or as a philosophical concept, not to  speak of as a theology. The notion of the ‘True One God’ as opposed to ‘False Many Gods’ was unknown to the Vedas, the Upanishads, the Buddhist and Jain Shastras, the Epics and the Puranas, and the six systems of Hindu philosophy. “Indian spirituality,” writes Ram Swarup, ‘proclaimed that the true Godhead was beyond number and count; that it had many manifestations which did not exclude or repel each other but included each other, and went together in friendship; that it was approached in different ways and through many symbols; that it resided in the hearts of its devotees. Here there were no chosen people, no exclusive prophethoods, no privileged churches and fraternities and ummas. The message was subversive of all religions based on exclusive claims.” This spirituality was summed up in the Vedic mantra,

speak of as a theology. The notion of the ‘True One God’ as opposed to ‘False Many Gods’ was unknown to the Vedas, the Upanishads, the Buddhist and Jain Shastras, the Epics and the Puranas, and the six systems of Hindu philosophy. “Indian spirituality,” writes Ram Swarup, ‘proclaimed that the true Godhead was beyond number and count; that it had many manifestations which did not exclude or repel each other but included each other, and went together in friendship; that it was approached in different ways and through many symbols; that it resided in the hearts of its devotees. Here there were no chosen people, no exclusive prophethoods, no privileged churches and fraternities and ummas. The message was subversive of all religions based on exclusive claims.” This spirituality was summed up in the Vedic mantra,

They hail It as Indra, as Mitra, as Varuna, as Agni, and as that divine and noble-winged GarutmAn. Truth (or Reality) is one; the wise ones speak of it in various ways, whether as Agni, or as Yama, or as MatarishvAn.

Monotheism came to this country for the first time as the war-cry of Islamic invaders who marched in with the Quran in one hand and the sword in the other. It proclaimed that there was no God but Allah and that Muhammad was the Prophet of Allah. It claimed that Allah had completed his Revelation in the Quran and that Muslims who possessed that Book were the Chosen People. It invoked a theology which called upon the believers to convert or kill the infidels, particularly the idolaters, capture their women and children and sell them into slavery and concubinage all over the world, slaughter their sages and saints and priests, break or at least desecrate their idols, destroy or convert into mosques their places of worship, plunder their properties, occupy their lands, and heap humiliations on such of them as cannot be converted or killed either due to their capacity for fighting back or the need of the conquerors for slave labour.

The enormities which the votaries of Islamic Monotheism practised on a vast scale and for a long time vis-a-vis Hindu religion, culture and society, were unheard of by Hindus in the whole of their hoary history. Muslim theologians, sufis and historians who witnessed or read or heard of these doings hailed the doers as soldiers of Allah and heroes of Islam.

The enormities which the votaries of Islamic Monotheism practised on a vast scale and for a long time vis-a-vis Hindu religion, culture and society, were unheard of by Hindus in the whole of their hoary history. Muslim theologians, sufis and historians who witnessed or read or heard of these doings hailed the doers as soldiers of Allah and heroes of Islam.

They thanked Allah and the Prophet who had declared a permanent war on the infidels and bestowed their progeny and properties on the believers. They quoted chapter and verse from the Quran and the Sunnah of the Prophet in order to prove that what was being done to Hindus was fully in keeping with the highest teachings of Islam.

The mainstream of Hinduism drew the inescapable conclusion that Islam was not much more than glorified gangsterism, and closed its doors to any willing contact with the hated creed and its vicious votaries. There was, however, a somewhat different response from some marginal sections of Hindu society.

We need not go into the objective and subjective factors which facilitated this response. The result was the same in every case. The doings of Islam were divorced from its doctrine and viewed as aberrations due to human failing. Its Monotheism was abstracted and absorbed as the doctrine of One God as against Many Gods. Finally, Islam was presented as good a religion as Hinduism. The saints who performed this feat are now known as the pioneers of the ‘Nirguna school of Bhakti’. Most of them show symptoms of the deep inroad which Monotheism had made into their psyche.

In the prevalent lore of present-day Hindu scholarship, the Nirguna school of Bhakti has become a ‘progressive movement of social protest’ inspired by the message of human equality and brotherhood supposed to have been brought in by Islam. There are several other myths which, joined together, make this school sound like a radical, even a revolutionary departure from the mainstream of Hinduism. A study of the literature produced by this school, however, provides no evidence that its saints said anything which had not been said long ago and in a loftier language by the ancient sages of Sanatana Dharma, or which was not being said by the other and contemporary school of Bhakti.

By and large, the Nirguna school, like the other school of Bhakti, was wedded to Vaishnavism and drew upon the Epics and the Puranas, particularly the Bhagavata, for its devotional stories and songs. What made the Nirguna school sound different in its historical setting was the stress which most of its saints laid on the ‘True One God (sacchA sAhib)’and the contempt they poured on idol worship (pAthar-pUjA). The Shaktas who worshipped the Great Mother were subjected to virulent attacks in the literature of this school. Allah of the Quran who brooked no partners, particularly of the female gender, and permitted no idol worship, had won a victory without his victims knowing it.

By and large, the Nirguna school, like the other school of Bhakti, was wedded to Vaishnavism and drew upon the Epics and the Puranas, particularly the Bhagavata, for its devotional stories and songs. What made the Nirguna school sound different in its historical setting was the stress which most of its saints laid on the ‘True One God (sacchA sAhib)’and the contempt they poured on idol worship (pAthar-pUjA). The Shaktas who worshipped the Great Mother were subjected to virulent attacks in the literature of this school. Allah of the Quran who brooked no partners, particularly of the female gender, and permitted no idol worship, had won a victory without his victims knowing it.

Some Jain monks succumbed to Monotheism in their own way. Jainism had no God who could be made exclusive, nor Gods and Goddesses who could be spurned. But it had its Tirthankaras whose idols were worshipped in its temples. There is evidence that the Sthanakavasi sect of the Svetambara school of Jainism renounced idol worship and turned its back on temples under the influence of Islam.

Islamic invasion was defeated in due course and Muslim rule disappeared from the greater part of the Hindu homeland. But Monotheism retained the prestige it had acquired during the days of Muslim dominance. This happened largely because medieval Hindu thinkers had refused or failed to study and understand Islamic Monotheism in all its ramifications and from its own sources.

Many Hindu writers and poets of the medieval period have left for posterity some graphic accounts of the Muslim behaviour pattern with all its essential ingredients – sack of cities and villages and massacre of whole populations, capture of women and children, humiliation of Brahmanas, breaking of sacred threads, burning of scriptures, slaughter of cows, desecration of idols, destruction of temples or their conversion into mosques, plunder of properties, and so on. But what we miss altogether in the whole of medieval Hindu literature is an insight into the belief system which produced this behaviour pattern. There is not even the hint of a curiosity as to why Muslims were doing what they were doing. No Hindu acharya – there were quite a few of this class during this period – is known to have had a close look at Allah or the Prophet or the Quran or the theology which sanctioned these dismal deeds. Islamic Monotheism was thus allowed to remain unchallenged as a religious doctrine.

Ram Swarup observes, “Hindus fought Muslim invaders and locally established Muslim dynasties but neglected to study the religious and ideological motives of the invaders. Hindu learning or whatever remained of its earlier glory, followed the old grooves and its texts and speculations remained unmindful of the new phenomenon in their midst. For example, even as late as the fourteenth century, when Malik Kafur was attacking areas in the far South, in the vicinity of the seat of Sri Ramanujacharya, the scholarly dissertations of disciples of the great teacher show no awareness of the fact.”

Ram Swarup observes, “Hindus fought Muslim invaders and locally established Muslim dynasties but neglected to study the religious and ideological motives of the invaders. Hindu learning or whatever remained of its earlier glory, followed the old grooves and its texts and speculations remained unmindful of the new phenomenon in their midst. For example, even as late as the fourteenth century, when Malik Kafur was attacking areas in the far South, in the vicinity of the seat of Sri Ramanujacharya, the scholarly dissertations of disciples of the great teacher show no awareness of the fact.”

He continues, “Hindus were masters of many spiritual disciplines; they had many Yogas and they had developed a science of inner exploration. There had been a continuing discussion whether the ultimate reality was dvaita or advaita.

It would have been very interesting and instructive to find out if any of these savants of Yoga ever met, on their inner journey, a Quranic being Allah (or its original, Jehovah of the Bible) who is jealous of other Gods, who claims sole sovereignty and yet whom no one knows except through a pet go-between, who uses the latter’s mouth to publish his decrees, who proclaims crusades and jihAd, who teaches to kill the unbelievers and destroy their temples and shrines and levy tribute on them and to convert them into hewers of wood and drawers of water.”

Monotheism which had survived the defeat of Islamic invasion was reinforced by Christianity which appeared on the Indian scene along with European Imperialism. Christian Monotheism was no different from that of Islam; both of them shared a common source in the Bible. Nor had Christian Monotheism lagged behind its Islamic variation in committing atrocities on a large scale, for a long time, and in many lands; in fact, Islam had followed in many respects the precedents set by Christianity.

But in the Indian context, Christian Monotheism had an advantage over that of Islam. Hindus had no opportunity to see the fierce face of Christianity except in the small Portuguese and French enclaves for a short time. By the time Christianity was active in India on any scale, it had suffered a steep decline in the estimation of the dominant Western elite; the rise of modern science, rationalism and secularism had knocked the bottom out of Christian theology and deprived it of its stranglehold on the state.

But in the Indian context, Christian Monotheism had an advantage over that of Islam. Hindus had no opportunity to see the fierce face of Christianity except in the small Portuguese and French enclaves for a short time. By the time Christianity was active in India on any scale, it had suffered a steep decline in the estimation of the dominant Western elite; the rise of modern science, rationalism and secularism had knocked the bottom out of Christian theology and deprived it of its stranglehold on the state.

The British conquerors of India were not willing to back the Christian missions with state power to any great extent; the missions were not allowed to use their tried and tested methods for ‘saving the Hindus from hell’.

Most Hindus felt offended when Christian missionaries used foul language vis-a-vis Hindu religion, culture and society and started making conversions. But few of them were equipped intellectually to identify the doctrine from which the language sprang and the attempts at conversion emanated. Christian missionaries were presenting themselves as worshippers of the ‘True One God’ and denouncing Hinduism as idolatry wedded to many Gods and Goddesses. Some

Hindus defended their pantheon in the best manner they knew and continued to worship in their traditional temples. But others, particularly those who had benefited from English education, took the missionary accusation to heart and started ransacking their own scriptures in search of the ‘True One God’ who could stand shoulder to shoulder with the God of Christianity. They ended by disowning the multiplicity of Gods and denouncing idol worship. They gave out a call for purging Hinduism of its ‘polytheism’ so that Hinduism could be saved. That is how the Hindu reform movements started in the nineteenth century.

The psychology that was at work in the reform movements is illustrated best by the rise of Raja Ram Mohun Roy to name and fame in a short time. He owed his fascination for Monotheism to his study of Islam. Hindus of Calcutta did not take to him kindly when he started denouncing polytheism and idol worship. It was only when he criticised the Christian doctrine of Trinity and the crude methods of Christian missionaries that the English educated gentry of Calcutta warmed up to him. He was hailed as a Hindu leader by this gentry when he discovered the ‘True One God’ in the Brahma of the Vedas and the Upanishads. The Brahmo Samaj he founded took the message to Madras, Malabar, Maharashtra. The North Western Provinces (now U.P.) and the Punjab.

The Arya Samaj, founded by Maharshi Dayananda, spread Monotheism over a larger area and among those sections of Hindu society which had never known it earlier. As a result, Hindu society seemed to acquire self-confidence. But the logic of what had been set in motion was remorseless.

The Arya Samaj, founded by Maharshi Dayananda, spread Monotheism over a larger area and among those sections of Hindu society which had never known it earlier. As a result, Hindu society seemed to acquire self-confidence. But the logic of what had been set in motion was remorseless.

The wheel turned full circle in the Punjab where Neo-Sikhism forced the lives and sayings of the Gurus into the framework of Monotheism borrowed bodily and wholesale from Islam and Christianity. Nothing could have been more distorted and dishonest. But the exercise succeeded because by this time the dominant and vocal section of Hindu intelligentsia had become votaries of Monotheism.

This section applauded when the Akalis drove out the Brahmana priests from the gurudwaras after accusing them of having installed idols of many Gods and Goddesses in places meant for the worship of the ‘True One God’. Hindus who had retained their reverence for the idols had to collect and install them elsewhere when they were thrown out of the gurudwaras. Mahatma Gandhi protested in vain when a temple inside the Harimandir at Amritsar was demolished; he was told that Sikhism did not permit idol worship in its holy places.

The Hindu reform movements had started with the best of intentions. They aspired to save Hindu society from the onslaught of Islam and Christianity. They also succeeded in stopping conversions. But in as much as they were rooted in reaction against Islam and Christianity rather than in a resurgence of the Hindu spiritual vision, they misfired in the long run. Instead of forging their own weapon of defence, they borrowed it from the adversary’s armoury. Small wonder that it boomranged and turned out to the disadvantage of the cause they had espoused.

In disowning the multiplicity of Hindu Gods, the Hindu reform movements tended to disown the rich heritage of Hindu art, architecture, sculpture, music, dance and literature which had developed round these divinities and had no other raison d’etre. It was not long before they forgot the very purpose, namely defence of Hinduism, for which they had placed themselves in the vanguard of Hindu society.

In disowning the multiplicity of Hindu Gods, the Hindu reform movements tended to disown the rich heritage of Hindu art, architecture, sculpture, music, dance and literature which had developed round these divinities and had no other raison d’etre. It was not long before they forgot the very purpose, namely defence of Hinduism, for which they had placed themselves in the vanguard of Hindu society.

Worse still, the reform movements created an elite which looked down upon its own people and became progressively alienated from them in most of its perceptions. The wide gulf that yawns at present between the two sections of Hindu society is illustrated best by their respective response to the remains of Hindu temples destroyed by the Islamic invaders.

It is not unoften that Hindus in the countryside chance upon remains of temples which lie scattered on some site and which have escaped the notice of the Archaeological Survey of India. Invariably, they collect these remains, cleanse them, install them under a tree or in an improvised temple, and start worshipping them. Experts from the Archaeological Survey who receive the report and visit the spot feel amused at the simplicity of these people. Sometimes the ‘heap’ consists entirely of the outer and decorative portions of a temple and does not contain a single figure of a God or Goddess, either in relief or in the round. But that does not make any difference to the worshippers. All they know and care for is that the remains came from a temple where their ancestors had worshipped at one time but which was subsequently destroyed by Muslims.

The story becomes entirely different when one visits the drawing rooms of the Hindu elite. One sees there an array of sculptures selected with care from the same ruins and installed on tasteful stands. But they draw no reverence from those who possess them. They are only antiques meant for interior decoration. One is expected to contemplate them for their lines and forms and place them properly in the history of Indian art.

The story becomes entirely different when one visits the drawing rooms of the Hindu elite. One sees there an array of sculptures selected with care from the same ruins and installed on tasteful stands. But they draw no reverence from those who possess them. They are only antiques meant for interior decoration. One is expected to contemplate them for their lines and forms and place them properly in the history of Indian art.

Woe betide the visitor who becomes curious as to how these idols which were once housed in some temple or temples have landed in a modern drawing room, and how they got mutilated or defaced or deprived of limbs. That sort of curiosity is most likely to be met with stunned silence or derisive smiles. One has exhibited one’s utter lack of the aesthetic sense. This irrelevant digging into a dead past is simply not done in polished society. Or, worse still, one has betrayed one’s inclination towards ‘Hindu communalism’, a dangerous disease in a society dedicated to Secularism.

It was not that voices in defence of Gods and their worship as idols were not raised while the Hindu reform movements surged forward. Some of these voices came from the tallest figures in the saga of India’s re-awakening to her ancient heritage. Swami Vivekananda had said that if idol worship could produce a spiritual master like Sri Ramakrishna, all honour to it.

Sri Aurobindo had expounded at length how the concrete images to which Vedic rishis addressed their hymns had emerged out of the deepest intuitions of spiritual consciousness. Mahatma Gandhi had avowed his reverence for idols and temples in unmistakable terms. But the voices, it seems, failed to impress the followers of these great men. The Ramakrishna Mission installed life-like statues of Sri Ramakrishna in the temples it built. Sri Aurobindo Ashram raised their own guru to the same status. Mahatma Gandhi has so far been spared that ‘honour’. His followers, however, are not known for their fondness for Hindu idols or temples.

What was worse, the Ramakrishna Mission and the Sri Aurobindo Ashram imbibed the theology of Monotheism in another respect, namely, the cult of the latest and the best which will not be bettered. in the eyes of the Mission, Sri Ramakrishna is no more a saint who sought and verified in his own experience the truths of Sanatana Dharma; he has become a ‘synthesis of all faiths’ including Islam and Christianity such as has never been seen in the past and will not be witnessed again in future! The Ashram hails Sri Aurobindo not as a great yogin and sage who explored and explained to the modern world the deepest insights of the Hindu spiritual tradition, but as the highest manifestation of the Divine in human history! Shades of Christ and Muhammad.

What was worse, the Ramakrishna Mission and the Sri Aurobindo Ashram imbibed the theology of Monotheism in another respect, namely, the cult of the latest and the best which will not be bettered. in the eyes of the Mission, Sri Ramakrishna is no more a saint who sought and verified in his own experience the truths of Sanatana Dharma; he has become a ‘synthesis of all faiths’ including Islam and Christianity such as has never been seen in the past and will not be witnessed again in future! The Ashram hails Sri Aurobindo not as a great yogin and sage who explored and explained to the modern world the deepest insights of the Hindu spiritual tradition, but as the highest manifestation of the Divine in human history! Shades of Christ and Muhammad.

The stalwarts of India’s re-awakening never claimed to be founders of new religions. Nor were they interested in Hinduism because it carried some exclusive message made known to mankind by some Hindu at some point in time. For them, Hinduism was Sanatana Dharma, that is, a spiritual vision valid at all times, in all places and for all people, and directly accessible to all seekers without the help of an historical intermediary. To the Buddha, a new way was suspect. He described his own way as that on which the Buddhas of the past had walked and the Buddhas of the future will walk. And that is Ram Swarup’s starting point in his book. He seeks the “higher meanings” of the Hindu pantheon not only because “it will add to our understanding of Hinduism, one of the most ancient and still one of the major world-religions” but also because, “it will throw light on the ancient Gods of many Asian and European countries, Gods by now so completely forgotten that we cannot study them directly.

“The Hindu pantheon,” observes Ram Swarup, “has changed to some extent but the old Gods are still active and are still understood though under modified names. Hindu India has a continuity with its past which other nations, which changed their religions at some stage, lack. It is known that the Hindu religion preserves many old layers and forms. Therefore, its study may link us not only with its own past forms but also with the religious consciousness, intuitions and forms that prevailed in the past in Europe, in Greece, in Rome, in many Scandinavian and Baltic countries, amongst the German and the Slavic peoples, and also in several countries of the Middle East. In short, the study may reveal a fundamental form of spiritual consciousness which is wider than its Hindu expression.” This emergence of similar spiritual insights and forms over a vast area was not an accident.

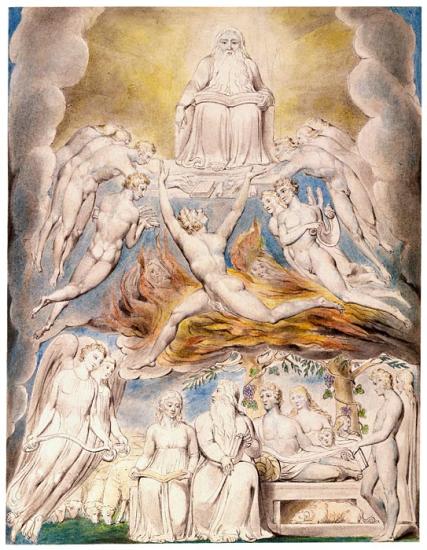

The earliest Hindu expression of that spiritual consciousness is found in the Vedas, “humanity’s oldest extant scripture.”Three things “stand out prominently” when we study the Vedic pantheon. Firstly, there is “a very large use of concrete images… many important Gods like Surya, Agni, Marut take their names after natural objects.” Secondly, “the spiritual consciousness of the race is expressed in terms of a plurality of Gods.” Thirdly, “all Gods have multiple names.” These are also features shared by the pantheons of many other peoples.

The earliest Hindu expression of that spiritual consciousness is found in the Vedas, “humanity’s oldest extant scripture.”Three things “stand out prominently” when we study the Vedic pantheon. Firstly, there is “a very large use of concrete images… many important Gods like Surya, Agni, Marut take their names after natural objects.” Secondly, “the spiritual consciousness of the race is expressed in terms of a plurality of Gods.” Thirdly, “all Gods have multiple names.” These are also features shared by the pantheons of many other peoples.

Ram Swarup starts with the Names of Gods which, in turn, lead him to an inquiry into the nature of language and the higher meanings of words. Taking up concrete images in the Vedic pantheon, he observes, “We have already seen that the physical and the intellectual are not opposed to one another. The names of physical objects become names of ideas, names of psychic truths, names of Gods; sensuous truths become intellectual truths, become spiritual truths… In fact, this is the only way in which the sense-bound mind understands something of the higher knowledge… This reverberating, echoing and imaging takes place up and down the whole corridor of the mind at all levels of abstraction. Here, as we traverse the path, we meet physical-forms, sound-forms, vision-forms, thought-forms, universal-forms, all echoes of each other.

We meet mantras and yantras and icons of various efficacies and psychic qualities. In one sense, they are not the light above but they are its important formations. They invoke the celestial and raise up the terrestrial…12 There is another reason why images in the Vedas and the Upanishads are concrete. When the fever of the soul subsides, when the mind becomes calm, when the spiritual consciousness opens, things are no longer lifeless.

We meet mantras and yantras and icons of various efficacies and psychic qualities. In one sense, they are not the light above but they are its important formations. They invoke the celestial and raise up the terrestrial…12 There is another reason why images in the Vedas and the Upanishads are concrete. When the fever of the soul subsides, when the mind becomes calm, when the spiritual consciousness opens, things are no longer lifeless.

In this state, things which have hitherto been regarded as ordinary are full of life, light and consciousness. In this state, ‘the earth meditates as it were; water meditates as it were; mountains meditate as it were.’ In this state, no need is felt to separate the abstract from the concrete because both are eloquent with the same message, because both image one another. In this state, everything expresses the divine; everything is the seat of the divine; everything is That; mountains, rivers and the great earth are but the TathAgata, as a Chinese teacher, Hsu Yun, proclaimed after his spiritual awakning.”

How did the Vedic sages see Gods in Nature’s mighty phenomena like the earth, the sky, the sun and the stars? “They saw in them sources and springs of their own lives; they saw that these things were part of one Great Life; that they were meeting points of great spiritual truths; that they revealed what was concealed; that they prefigured a mighty design; that they were kith and kin, friends and lovers. But in order to yield their deeper meanings, they demanded continued fellowship. This the old sages gave ungrudgingly and joyfully. They filled their hearts and the fullness of their hearts broke out in songs of praise.”

Coming to the plurality of the Vedic Gods and their names, he comments, “The names of Gods are not names of external beings. These are the names of the truths of man’s own higher self. So the knowledge of the epithets of Gods is a form of self-knowledge. Gods and their names embody truths of the deeper Spirit and meditation on them in turn invokes those truths. But those truths are many and, therefore Gods and their names too are many, though they are all held together in the unity of a spiritual consciousness.”

Coming to the plurality of the Vedic Gods and their names, he comments, “The names of Gods are not names of external beings. These are the names of the truths of man’s own higher self. So the knowledge of the epithets of Gods is a form of self-knowledge. Gods and their names embody truths of the deeper Spirit and meditation on them in turn invokes those truths. But those truths are many and, therefore Gods and their names too are many, though they are all held together in the unity of a spiritual consciousness.”

Equipped with this perspective on the nature of spiritual consciousness and its inevitable expressions, Ram Swarup proceeds to examine Monotheism and Polytheism. He finds merit in both of them so long as they remain spiritual ideas and do not become intellectual concepts.

“The Spirit,” he observes, “is a unity. It also worships nothing less than the Supreme. Monotheism expresses, though inadequately, this intuition of man for unity and for the Supreme… When the urge for unity is spiritual, the theology of One God is no bar and the seeker reaches a position no different from Advaita, from ekam sat. He realizes that God alone is, and not that there is only One God. But if the motive for unity is merely intellectual, it helps little spiritually speaking. God remains an outward being and does not become the truth of the Spirit.

It does not even help to reduce the number of Gods; instead it multiplies the number of Devils – if Christianity is any guide in the matter. We know Medieval Christianity was chockful of them. In fact, they occupied the centre of attention of the Church for many centuries to the exclusion of everything else. During these centuries it was difficult to say whether the Church worshipped God or these devils… The Church also abounded in Gods though they were not as plentiful as the devils. But these were not recognised as such because they appeared in the guise of angels, cherubims and seraphims.”

Coming to Polytheism, he comments, “If monotheism represents man’s intuition for unity, polytheism represents his urge for differentiation. Spiritual life is one but it is vast and rich in expression.

Coming to Polytheism, he comments, “If monotheism represents man’s intuition for unity, polytheism represents his urge for differentiation. Spiritual life is one but it is vast and rich in expression.

The human mind also conceives it differently. If the human mind was uniform, without depths, heights and levels of subtlety or if all men had the same mind, the same imagination, the same needs; in short, if all men were the same, then perhaps One God would do. But a man’s mind is not a fixed quantity and men and their powers and needs are different. So only some form of polytheism alone can do justice to this variety and richness. Besides this variety of human needs and human minds, the spiritual reality itself is so vast, immense and inscrutable that man’s reason fails and his imagination and fancy stagger.

Therefore this reality cannot be indicated by one name or formula or description. It has to be expressed in glimpses from many angles. No single idea or system of ideas could convey it adequately. This too points to the need for some form of polytheism.”

“The Vedic approach,” concludes Ram Swarup, “is perhaps the best. It gives unity without sacrificing diversity. In fact, it gives a deeper unity and a deeper diversity beyond the power of ordinary monotheism and polytheism. It is one with the yogic and the mystic approach20… In this deeper approach, the distinction is not between a true One God and false Many Gods; it is between a true way of worship and a false way of worship.

“The Vedic approach,” concludes Ram Swarup, “is perhaps the best. It gives unity without sacrificing diversity. In fact, it gives a deeper unity and a deeper diversity beyond the power of ordinary monotheism and polytheism. It is one with the yogic and the mystic approach20… In this deeper approach, the distinction is not between a true One God and false Many Gods; it is between a true way of worship and a false way of worship.

Wherever there is sincerity, truth and self-giving in worship, that worship goes to the true altar by whatever name we may designate it and in whatever way we may conceive it. But if it is not desireless, if it has ego, falsehood, conceit and deceit in it, then it is unavailing though

it may be offered to the most true God, theologically speaking.

Summing up, Ram Swarup says, “The truth is that the problem of One or Many Gods is born of a theological and not of a mystic consciousness. In the Atharvaveda, the sage Vena says that he ‘sees That in that secret station of the heart in which the manifoldness of the world becomes one-form’… But in another station of man, where not his soul but his mind rules, there is opposition between the One and the Many, between God and Matter, between God and Gods.

On the other hand, when the soul awakens, Gods are born in its depths which proclaim and glorify one another. Gods are bound to appear when the spiritual consciousness awakens; though in another sense they also fall away, God as well as Gods, with all their outward, anthropomorphic forms, and along with all our conceptions of them, however sublime and. exalted. Yes, even God falls away. For there is a spiritual consciousness which can do without God. Buddhism, Jainism, SAMkhya, Taoism and Zen confirm the truth of this observation. In fact, in Buddhism and Jainism, though Gods are plentiful, there is very little of One God. Yet in spiritual perception, insight and attainment, these religions are not less than those where One God rules the roost and is the sole cock of the walk.”

Monotheism as known to history is not born of spiritual seeking. Ram Swarup says, “Monotheism was not always a spiritual idea. In many cases it was an ideology. It was consolidated in wars and in turn it led to further wars… there was a larger association to create, an empire to consolidate, or other nations and tribes to conquer, and the idea of a ‘One True God’ was handy in the pursuit of this object. The diplomacy, the sword, systematic vandalism, all played their part in making a particular god supreme. From very early days, the One God of Christianity was bound up with the imperial needs of Rome. In more recent times, the Biblical God has tried to consolidate what the European arms and trade have conquered…

Monotheism as known to history is not born of spiritual seeking. Ram Swarup says, “Monotheism was not always a spiritual idea. In many cases it was an ideology. It was consolidated in wars and in turn it led to further wars… there was a larger association to create, an empire to consolidate, or other nations and tribes to conquer, and the idea of a ‘One True God’ was handy in the pursuit of this object. The diplomacy, the sword, systematic vandalism, all played their part in making a particular god supreme. From very early days, the One God of Christianity was bound up with the imperial needs of Rome. In more recent times, the Biblical God has tried to consolidate what the European arms and trade have conquered…

In the cultural history of the world, the replacement of Many Gods by One God was accompanied by a good deal of conflict, vandalism, bigotry, persecution and crusading. These conflicts were very much like the ‘wars of liberation’ of today, hot and cold, openly aggressive or cunningly subversive. Success in such wars played no mean role in making a local deity, say Allah of certain Arab tribes, win a wider status and assume a larger monarchical role… This point needs stressing. For in the past, the controversy between One God and Many Gods or between My True God and Your False God led to many rolling of heads and much spilled blood, and even today there is no dearth of hot heads and the discussion still tends to polemics, bad blood, and frayed tempers. There are still organised churches and missions out to make war on the false Gods of the heathens.

On the other hand, Polytheism “bred a spirit of religious tolerance and freedom” wherever it prevailed. “Ancient Rome, Greece and Egypt – all polytheistic cultures – were relatively free from religious wars… Rome, Alexandria and Athens were open places where different religions met and discussed freely. When St. Paul visited Athens, he was invited by the Athenians to speak about his doctrine.

On the other hand, Polytheism “bred a spirit of religious tolerance and freedom” wherever it prevailed. “Ancient Rome, Greece and Egypt – all polytheistic cultures – were relatively free from religious wars… Rome, Alexandria and Athens were open places where different religions met and discussed freely. When St. Paul visited Athens, he was invited by the Athenians to speak about his doctrine.

He did not avail himself of the opportunity but it is obvious that he did not feel at home in this atmosphere of free enquiry… St. Paul represented not the spirit’s impatience with what is only cerebral but a passionate attachment to a fixed idea which is closed to wider viewpoints and larger truths of life. In polytheistic Rome too, men of different religious persuasions and sects met and built their temples and worshipped in their own way. But this freedom disappeared when Christianity, the religion of One True God, took over.”

Ram Swarup, therefore, calls upon the people of various countries in Asia, Africa, Europe and America to return to their ancient Gods which have been replaced by the semitic Gods in the recent past. “It would, therefore, be difficult,” he writes, “to hold that the present Gods of semitic origin are superior to the now defunct pagan Gods. There was a time when the old pagan Gods were pretty fulfilling and they inspired the best of men and women to acts of greatness, love, nobility, sacrifice and heroism. It is, therefore, a good thing to return to them in thought and pay them our homage. We know pilgrimage, as ordinarily understood, as wayfaring to visit a shrine or a holy place. But there can also be a pilgrimage in time and we can journey back and make our offerings of the heart to those Names and Forms and Forces which once incarnated and expressed man’s higher life. They are holy Names and Symbols.”

Restoration of old Gods will restore among the people concerned a respect for their past. It will also fill the gap in their cultural history. “The present generations of many countries tend to regard their past as a benighted period of their history. A more understanding approach towards their Gods of old will work for a less severe judgement about their past and their ancestors. It will also fill the generation gap, not the one we talk about the most these days but a still wider one, the general rootlessness of a whole nation. Gods provide an invisible link between the past and the present of a nation; when they go, the link also snaps. The peoples of Egypt, Persia, Greece, Germany and the Scandinavian countries are no less ancient than the people of India; but they lost their Gods, and therefore they lost their sense of historical continuity and identity.”

Restoration of old Gods will restore among the people concerned a respect for their past. It will also fill the gap in their cultural history. “The present generations of many countries tend to regard their past as a benighted period of their history. A more understanding approach towards their Gods of old will work for a less severe judgement about their past and their ancestors. It will also fill the generation gap, not the one we talk about the most these days but a still wider one, the general rootlessness of a whole nation. Gods provide an invisible link between the past and the present of a nation; when they go, the link also snaps. The peoples of Egypt, Persia, Greece, Germany and the Scandinavian countries are no less ancient than the people of India; but they lost their Gods, and therefore they lost their sense of historical continuity and identity.”

Such a restoration is particularly relevant for the peoples of Africa and South America. “The countries of these continents have recently gained political freedom of a sort, but it has done little to help them and to give them a spiritual identity. If they wish to rise in a deeper sense, they must recover their soul, their Gods, their roots in their own psyche; there has to be a spiritual reassertion, a resurrection of their Gods. If they need any change, and there is no doubt they do, it must come from within themselves as a part of their own experience. If they do enough self-churning, then their own Gods will put forth new meanings in response to their new needs. They have to make the best of their own psychic and spiritual gifts and discover their own Gods within themselves. No people can import their Gods ready-made and rise spiritually under the aegis of imported deities, saviours and prophets.”

The old Gods are not dead; they have only withdrawn themselves. “If there is sufficient aspiration, invoking, and soliciting, there is no doubt that even Gods apparently lost could come back again. They are there all the time. For nothing that has any truth in it can be destroyed. It merely goes out of manifestation; but it could reappear under propitious circumstances. So could the old Gods come to life again in response to new summons.”

It was quite apt that a review of Ram Swarup’s book which appeared in The Times of India dated March 29, 1981 described it as a call for “The Return of the Gods”. The reviewer was the noted scholar from Santiniketan, Dr. Sisir Kumar Ghose. He was well-known as an exponent of Sri Aurobindo’s thought.

It was quite apt that a review of Ram Swarup’s book which appeared in The Times of India dated March 29, 1981 described it as a call for “The Return of the Gods”. The reviewer was the noted scholar from Santiniketan, Dr. Sisir Kumar Ghose. He was well-known as an exponent of Sri Aurobindo’s thought.

Five years later, Ram Swarup examined Monotheism more concretely, that is, its unfoldment in the form of Islam and Christianity. “The spiritual equipage of Islam and Christianity,” he wrote, “is similar; their spiritual contents, both in quality and quantum, are about the same. The central piece of the two creeds is ‘One True God’ of masculine gender who makes himself known to his believers through an equally favoured individual. The theory of mediumistic communication has not only a psychology; it has also a theology laid down long ago in the oldest part of the Bible in the Deuteronomy (18.19-20).

The Biblical God says that he will speak to his chosen people through his chosen prophet: ‘I will tell him what to say, and he will tell the people everything I command. I will punish anyone who refuses to obey him’ (Good News Bible). The whole prophetic spirituality, whether found in the Bible or in the Quran, is mediumistic in essence. Here everything takes place through a proxy, through an intermediary. Here man knows God through a proxy; and probably God too knows man through the same proxy. The proxy is the favoured individual, a privileged mediator. ‘No one knows the Son except the Father, and no one knows the Father except the Son and anyone to whom the Son chooses to reveal him,’ says the Bible (Matt.XI. 27). The Quran makes no very different claim. ‘This day I have perfected your religion,’ says the Allah of the Quran through his last prophet (5.3).”

He thought that the time had come for Hindus to evaluate Christianity and Islam in terms of Hindu spirituality. “Hitherto we have looked on Hinduism through the eyes of Islam and Christianity. Let us now learn to look at these ideologies from the vantage point of Hindu spirituality – they are no more than ideologies, lacking as they are in the integrality and inwardness of true religion and spirituality. Such an exercise would also throw light on the self-destructiveness of modern ideologies of Communism and Imperialism, inheritors of the prophetic mission or ‘burden’ in its secularised version of Christianity and Islam. The perspective gained will be a great corrective and will add a new liberating dimension; it will help not only India and Hinduism but the whole world.”

Respect for Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism, and revolt against closed theologies was already growing in the world. “Dogmas are under a cloud; claims on behalf of Last Prophethood and Only Sonship, hitherto enforced through great intellectual conditioning, browbeating and the big stick, are becoming unacceptable. Religions of proxy are in retreat.

Respect for Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism, and revolt against closed theologies was already growing in the world. “Dogmas are under a cloud; claims on behalf of Last Prophethood and Only Sonship, hitherto enforced through great intellectual conditioning, browbeating and the big stick, are becoming unacceptable. Religions of proxy are in retreat.

More and more men now seek authentic experience. Men and women are ceasing to be obedient believers and are becoming seekers. They no longer want to be anybody’s sheep, now that they know they can be their own shepherds. An external authority, even when it is called God in certain scriptures, threatening and promising alternately, is increasingly making less and less impression; people now realize that Godhead is their own true, secret status and they seek it in the depths of their own being. All this is in keeping with the wisdom of the East.

Ram Swarup completed his evaluation of the semitic creeds by locating them in their proper place on the map of the Samkhya-Yoga philosophy and psychology which are shared in common by all schools of Sanatana Dharma. He pointed out that the traditional commentators on Yoga had concentrated on the yogic or ekAgra samAdhi and neglected treatment of non-yogic samAdhis. It was, however, the non-yogic samAdhis which held the key to an understanding of the psychic phenomena which do not have their source in the yogic samAdhi. We shall quote him at some length:

Considering that the two kinds of samAdhis are not unoften confused with each other, it would have served the cause of clarity if both were discussed and their differences pointed out. After all, the Gita does it; in its last two chapters, it discusses various spiritual truths like austerity, faith, duty, knowledge in their triple expression and sharply distinguishes their sAttvika from their rAjasika and tAmasika imitations.

The elucidation of non-yogic samAdhis or ecstasies has also its positive value and peculiar concern. It could help to explain quasi-religious phenomena which, sadly, have been only too numerous and too important in the spiritual history of man. Many creeds seemingly religious sail under false labels and spread confusion. As products of a fitful mind, they could ‘not but make only a temporary impression and their life could not but be brief. But as projections of a mind in some kind of samAdhi, they acquire unusual intensity, a strength of conviction and tenacity of purpose (mUDhagraha) which they could not otherwise have.

We may say that even the lower bhUmis (kAma-bhUmis) have their characteristic trances or samAdhis, their own Revelations, Prophets and Deities. They project ego-gods and desire-gods and give birth to dvesha-dharmas and moha-dharmas, hate religions and delusive ideologies. All these projections have qualities very different from the qualities of the projections of the yogic bhUmi.

For example, the God of the yoga-bhUmi of PAtaNjala Yoga is free, actually and potentially, from all limiting qualities like desire, aversion, hankering, ego and nescience; free from all actions, their consequences, present or future, active or latent. Or in the language of PAtaNjala Yoga, he is untouched by klesha-karma-vipAka-Ashaya. But the god of the ecstasies of non-yogic bhUmi or kAma-bhUmi is very different. He has strong likes and dislikes and has cruel preferences. He has his favorite people, churches and ummas and his implacable enemies. He is also very egoistic and self-regarding; he can brook no other god or gods. He insists that all gods other than himself are false and should not be worshipped.

He is a ‘jealous god’, as he describes himself in the Bible. And he ‘whose name is jealous’ is also full of ‘fierce anger’ (aph) and cruelty. He commands his chosen people that when he has brought them to the promised land and delivered its people into their hands, ‘thou shalt smite them, and utterly destroy them; thou shalt make no covenant with them, nor show mercy unto them… ye shall destroy their altars, and break down their images, and cut down their groves… For thou art an holy people unto the Lord…’ (Deut. 7. I-6

The Allah of the Quran exhibits about the same qualities. He is a god of wrath (ghazb); on those who do not believe in him and his prophets, he wreaks a terrible punishment (azAb al-azeem). In the same vein, he is also a mighty avenger (azeez-ul-intiqAm). He is also a god of ‘plenteous spoils’ (mUghanim kasIr, 4.94).

The Allah of the Quran exhibits about the same qualities. He is a god of wrath (ghazb); on those who do not believe in him and his prophets, he wreaks a terrible punishment (azAb al-azeem). In the same vein, he is also a mighty avenger (azeez-ul-intiqAm). He is also a god of ‘plenteous spoils’ (mUghanim kasIr, 4.94).

He tells the -believers how he repulsed their opponents and caused them to inherit the land, the houses and the wealth of the disbelievers (33.27). He closely follows the spirit of Jehovah who promised his chosen people that he would give them ‘great and goodly cities they builded not, and wells which they digged not, vineyards and olive trees they planted not’ (Deut. 6.10-11).

No wonder this kind of god inspired serious doubts and questions, among thinking people. Some of his followers like Philo and Origen allegorized him to make him more acceptable. Some early Christian gnostics simply rejected him. They said that he was an imperfect being presiding over an imperfect moral order; some even went further and regarded him as the principle of Evil. Some gnostic thinkers called him ‘Samael’, a blind God or the God of the blind; others called him ‘Ialda baoth’, the son of Chaos.

He continues to offend the moral sense of our rational age too. Thomas Jefferson thinks that the ‘Bible God is a being of terrific character, cruel, vindictive, capricious and unjust.’ Thomas Paine (1737-1809) says of the Bible that ‘it would be more consistent that we call it the work of a demon than the word of God.’

Hindus will buy any outrages if they are sold as Gods, Saints, or Prophets. They have also a great weakness for what they describe as ‘synthesis’. In that name, they will lump together most discordant things without any sense of their propriety and congruity, intellectual or spiritual. However, a few names like Bankim Chandra, Swami Dayananda, Vivekananda, Aurobindo and Gandhi are exceptions to the rule.

To Bankim, the God of the Bible is ‘a despot’ and Jesus’s doctrine of ‘eternal punishment’ in the ‘everlasting Fire’ (Matt. 25. 41) is ‘devilish’. Swami Dayananda remembering -how the Biblical ‘Lord sent a pestilence… and there fell seventy thousand men of Israel’ (I Chr. 21.14), His Chosen people, observes that even ‘the favour of a capricious God so quick in His pleasure is full of danger’, as the Jews know it only too well. Similarly, the Swami argues, in his usual unsparing way, that the Allah and Shaitan of the Quran, according to its own showing, are about the same.

But to reject is not to explain. Why should a god have to have such qualities? And why should a being who has such qualities be called a god? And why should he have so much hold? Indian Yoga provides an answer. It says that though not a truly spiritual being, he is thrown up by a deeper source in the mind. He is some sort of a psychic formation and carries the strength and attraction of such a formation. He also derives his qualities and dynamism from the chitta-bhUmi in which he originates.

It will explain that the Biblical God is not peculiar and he is not a historical oddity. He has his source in man’s psyche and he derives his validity and power from there; therefore he comes up again and again and is found in cultures widely separated. This god has his own ancestry, his own sources from which he is fed, his own tradition and principle of continuity, self-renewal and self validation.

Not many know that a similar God, Il Tengiri, presided also over the life of Chingiz Khan and bestowed on him Revelations. Minhajus Siraj, the mid-thirteenth century historian, tells us in his TabqAt-i-NAsiri, that ‘after every few days, he (Chingiz Khan) would have a fit and during his unconsciousness he would say all sorts of things… Some one would write down all he said, put (the papers) in a bag and sealed them. When Chingiz recovered consciousness, everything was read out to him and he acted accordingly. Generally, in fact always, his designs were successful.’

Not many know that a similar God, Il Tengiri, presided also over the life of Chingiz Khan and bestowed on him Revelations. Minhajus Siraj, the mid-thirteenth century historian, tells us in his TabqAt-i-NAsiri, that ‘after every few days, he (Chingiz Khan) would have a fit and during his unconsciousness he would say all sorts of things… Some one would write down all he said, put (the papers) in a bag and sealed them. When Chingiz recovered consciousness, everything was read out to him and he acted accordingly. Generally, in fact always, his designs were successful.’

In this, one can see unmistakable resemblance with the revelations or wahi of the semitic tradition. In actual life, one seldom meets truths of the kAma-bhUmi unalloyed. Often they are mixtures and touched by intrusions from the truths of the yoga-bhUmi above.

This however makes them still more virulent; it puts a religious rationalization on them. It degrades the higher without uplifting the lower. The theories of jihAd, crusades, conversions and da‘wa become spiritual tasks, Commandments of God, religious obligations, vocations and duties of a Chosen People. ‘See my zeal for the Lord’, says Jehu, an army captain anointed as king at the command of Jehovah. Bound to follow His will, he called all the prophets, servants, priests and worshippers of rival Baal on the pretext of organising his service and when they were gathered, his guards and captains ‘smote them with the edge of the sword’ and ‘they brake down the image of Baal, and brake down the house of Baal, and made it a draught house (latrine) unto this day’ (2 Kings 10. 25, 27).

This characterisation of the Semitic creeds, their gods, their scriptures and their prophets was bound to bring about a radical change in the Hindu assessment of Christianity. More and more Hindu thinkers and scholars are going to primary sources rather than remain satisfied with the professions of the Christian missionaries.

By By Sita Ram Goel

(5376)

Born in Calcutta, Sri Aurobindo was sent to England for his studies at the tender age of six. After his schooling he went on to study at Cambridge University in 1890.

Born in Calcutta, Sri Aurobindo was sent to England for his studies at the tender age of six. After his schooling he went on to study at Cambridge University in 1890. While in England, Aurobindo had observed the society first hand, and learnt its strengths and weaknesses. He figured that it wouldn’t be in anybody’s interest to blindly imitate European ideas without understanding the basis of one’s own culture and civilisation.

While in England, Aurobindo had observed the society first hand, and learnt its strengths and weaknesses. He figured that it wouldn’t be in anybody’s interest to blindly imitate European ideas without understanding the basis of one’s own culture and civilisation.

Sri Aurobindo continued writing for the public through a monthly magazine called the Arya. He gradually withdrew into increasingly intense spiritual practice, leaving the material responsibility of the disciples and the growing ashram to a lady named Mira, who is affectionately called “The Mother”. In these years of deep meditation he delved deep into the depths of the spirit. His aim was to fully discover and map out the path to a divine future for the world. The discoveries he made were through direct realisation of many divine mysteries, in the same way as the Vedic Rishis.

Sri Aurobindo continued writing for the public through a monthly magazine called the Arya. He gradually withdrew into increasingly intense spiritual practice, leaving the material responsibility of the disciples and the growing ashram to a lady named Mira, who is affectionately called “The Mother”. In these years of deep meditation he delved deep into the depths of the spirit. His aim was to fully discover and map out the path to a divine future for the world. The discoveries he made were through direct realisation of many divine mysteries, in the same way as the Vedic Rishis. He also wrote plays, poetry and stories. He presented a Hindu view on international issues such as war, self-determination, the possibility of international unity, as well as the shortcomings and potentials arising from the League of Nations which had been set up following the First World War.

He also wrote plays, poetry and stories. He presented a Hindu view on international issues such as war, self-determination, the possibility of international unity, as well as the shortcomings and potentials arising from the League of Nations which had been set up following the First World War.  15th August 1947, First News Paper of INDEPENDENT INDIA

15th August 1947, First News Paper of INDEPENDENT INDIA Of recent years there has been an academic controversy amongst the more scholarly followers of Sri Aurobindo on the subject of whether he should be considered a Hindu and whether his teachings could be classed as Hinduism. Unfortunately there are many western or westernised Indian followers of Hindu gurus who will do their utmost to dissociate themselves from the word “Hindu” which Hindu author and writer Rajiv Malhotra refers to the syndrome as the U- Turn

Of recent years there has been an academic controversy amongst the more scholarly followers of Sri Aurobindo on the subject of whether he should be considered a Hindu and whether his teachings could be classed as Hinduism. Unfortunately there are many western or westernised Indian followers of Hindu gurus who will do their utmost to dissociate themselves from the word “Hindu” which Hindu author and writer Rajiv Malhotra refers to the syndrome as the U- Turn All the thousands of true Hindu sages through the passage of time have always said that their teachings are universal, and have had a concern for all humanity. This does not make them non-Hindu. This just means that at its core – Hinduism itself is universal and embraces the whole of humanity, allowing all to drink the nectar of its wisdom without giving up their identity. But they don’t want to attribute the quality of universalism to Hinduism, because it is unfashionable; Hinduism being associated in the media with backwardness and social ills.

All the thousands of true Hindu sages through the passage of time have always said that their teachings are universal, and have had a concern for all humanity. This does not make them non-Hindu. This just means that at its core – Hinduism itself is universal and embraces the whole of humanity, allowing all to drink the nectar of its wisdom without giving up their identity. But they don’t want to attribute the quality of universalism to Hinduism, because it is unfashionable; Hinduism being associated in the media with backwardness and social ills. This is quite wrong. Sri Aurobindo acknowledges (and nobody would dare argue otherwise) that he first achieved direct spiritual experience reflecting upon and practicing the yoga of the Bhagavad Gita and Upanishads, with intense devotion to Krishna. Without these he would not have been able to achieve his spiritual realisations, and develop his philosophical teachings. On the other hand, modern science was not developed by persons who were following a Christian line of thought or enquiry. It was developed by enquiry and study into material reality, independently of religion.

This is quite wrong. Sri Aurobindo acknowledges (and nobody would dare argue otherwise) that he first achieved direct spiritual experience reflecting upon and practicing the yoga of the Bhagavad Gita and Upanishads, with intense devotion to Krishna. Without these he would not have been able to achieve his spiritual realisations, and develop his philosophical teachings. On the other hand, modern science was not developed by persons who were following a Christian line of thought or enquiry. It was developed by enquiry and study into material reality, independently of religion. The development of modern science did not flow out of Christianity. In some respects it developed in spite of Christianity. The Church often tried to silence persons whose research led them to propose hypotheses that went against certain Christian notions such as the world being 6,000 years old, the world being flat, and the sun going round the Earth, opposition to the theory of evolution etc. By contrast, Sri Aurobindo faced not one iota of difficulty or persecution from the Hindu orthodoxy in publishing whatever he wanted to and pursuing whatever line of spiritual enquiry and experiences he preferred.

The development of modern science did not flow out of Christianity. In some respects it developed in spite of Christianity. The Church often tried to silence persons whose research led them to propose hypotheses that went against certain Christian notions such as the world being 6,000 years old, the world being flat, and the sun going round the Earth, opposition to the theory of evolution etc. By contrast, Sri Aurobindo faced not one iota of difficulty or persecution from the Hindu orthodoxy in publishing whatever he wanted to and pursuing whatever line of spiritual enquiry and experiences he preferred. But today, amongst Indian politicians (apart from Dr Karan Singh, a scholar on Sri Aurobindo), everybody quotes conveniently from Gandhi, although nobody applies his ideals of charkha, non-violence, khadi and birth control by sexual abstinence. No journalist ever mentions this extraordinary yogi, whose sayings of one hundred years ago are still one hundred per cent relevant today. Not only is he absent from schools and universities, in some manuals written by the Congress, he is branded a ‘terrorist’. Shame on India!

But today, amongst Indian politicians (apart from Dr Karan Singh, a scholar on Sri Aurobindo), everybody quotes conveniently from Gandhi, although nobody applies his ideals of charkha, non-violence, khadi and birth control by sexual abstinence. No journalist ever mentions this extraordinary yogi, whose sayings of one hundred years ago are still one hundred per cent relevant today. Not only is he absent from schools and universities, in some manuals written by the Congress, he is branded a ‘terrorist’. Shame on India!

Ramana was 16 when he experienced this out of the blue. Until then he was a normal boy, tall, strong, a good football player and swimmer. In studies also he was not bad thanks to his phenomenal memory.

Ramana was 16 when he experienced this out of the blue. Until then he was a normal boy, tall, strong, a good football player and swimmer. In studies also he was not bad thanks to his phenomenal memory. Ramana stayed for 17 years in the Virupaksha cave and five more years in a cave, called Skandashram, further up on Arunachala. Now, several people lived with him, among them his mother and younger brother.

Ramana stayed for 17 years in the Virupaksha cave and five more years in a cave, called Skandashram, further up on Arunachala. Now, several people lived with him, among them his mother and younger brother. A thread runs through whatever Ramana Maharshi says:

A thread runs through whatever Ramana Maharshi says: Ramana took the analogy even further: in the same way, as the role of an actor is determined, so are the actions of a body. Does this mean the individual has no free will? He clarified: As long as one considers oneself to be an individual person, one has free will and has to use it well – and this concerns probably all of us. On the other hand, Ramana claimed, “the purpose of one’s birth will be fulfilled whether you will it or not.” And then intriguingly added: “Let the purpose fulfil itself.”

Ramana took the analogy even further: in the same way, as the role of an actor is determined, so are the actions of a body. Does this mean the individual has no free will? He clarified: As long as one considers oneself to be an individual person, one has free will and has to use it well – and this concerns probably all of us. On the other hand, Ramana claimed, “the purpose of one’s birth will be fulfilled whether you will it or not.” And then intriguingly added: “Let the purpose fulfil itself.”

In the days of old, Hindu culture like Hindu religion was a creation of the devil. It had to be scrapped and the stage swept clean for the culture of Christianity to take over. In the new language, Hindu culture was credited with great creations in philosophy, literature, art, architecture, music, painting and the rest. There was reservation only at one point. This culture, it was said, had stopped short of reaching the crest because its spiritual perceptions were deficient, even defective. It could surge forward on its aborted journey only by becoming a willing vehicle for ‘Christian truths’.