Author Archive

Savarkar and Modi, beginning and end of Hindutva

Hate mongers Hate mongers often need concocted stories to buttress their political message. In India, these are most common in that peculiar Indian form of hatred: anti-Brahminism. As the local counterpart to what anti-Semitism...

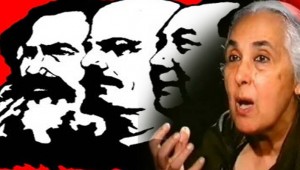

Romila Thapar mistakes Hindu impotent rage for a pro-Hindu power equation

According to retired history professor Romila Thapar, “academics must question more” (The Hindu, October 27, 2014). She was delivering the third Nikhil Chakravartty Memorial Lecture, eloquently titled: “To Question or not...

Looney Marxist Historian Attacks Arun Shourie

D.N. Jha’s “Reply to Arun Shourie”, dated 3 July 2014, was published in shorter form as “Grist to the reactionary mill”, Indian Express, 9 July 2014. It starts as follows: “I was amused to read ‘How History Was Ma...

Romila Thapar’s Marxist Rant on ICHR nomination

Retired historian Romila Thapar has written an opinion piece (“History repeats itself”, 11 July 2014, India Today) giving the standard secular reaction to the appointment of equally retired historian Y. Sudershan Rao as cha...

‘Marxist’ History in the Unmaking

“Modi’s accession to power and the respect he clearly enjoys among the neighbouring governments—and even in the US—may well be an apt occasion to rethink our attitude towards the ideological power struggle in India. So ...

How Buddha was turned Anti Hindu

Orientalists have started treating Buddhism as a separate religion because they discovered it outside India, without any conspicuous link with India, where Buddhism was not in evidence. At first, they didn’t even know that th...

Aryan Re-Invasion Theory

An Indo-European Conference The Indogermanische Gesellschaft organizes a conference every year. It must be one of the few international conferences where German is still spoken, along with English. I don’t know why I had neve...

A Pakistani in search of a homeland

In Eurasia Review on 25 December 2012, Khan A. Sufyan published a paper titled: “Pakistan: The True Heir Of Indus Valley Civilization – Analysis”. In it, he argues that Pakistan is not just the state for South-Asian Musli...

The lost honour of India studies

S.N. Balagangadhara, better known as Balu, is Professor of Comparative Culture Studies in Ghent University, Belgium. Balu is a Kannadiga Brahmin by birth, a former Marxist, and his discourse has a very in-your-face quality. In ...

Origins of Anti-Brahminism

The true prophets of the anti-Brahmin message were no doubt the Christian missionaries. In the sixteenth century, Francis Xavier wrote that Hindus were under the spell of the Brahmanas, who were in league with evil spirits, and...

12